In Part 1 of our Country music lyrics analysis, Danny Katz scans 20K Country tracks to determine whether more country songwriters means less originality over time.

by Danny Katz from Chartmetric

In early February, singer-songwriter and Country music’s fastest rising superstar Zach Bryan signed a global publishing deal with Warner Chappell Music. Despite having recorded his debut album while still enlisted in the United States Navy four years ago, Bryan is Chartmetric’s seventh ranked Country artist. Since then, he has charted an extremely unlikely, meteoric rise to the top by doing things his way: releasing unparalleled amounts of music featuring raw, poetic language over organic instrumentation.

Bryan is arguably Country music’s most intriguing storyline due to his unconventional methods, one of which he himself highlighted in the press release of his signing. When asked about Warner Chappell, the first distinguishing quality he mentioned was that “they never pushed a four-man writing team on me.” Unlike the majority of Country artists (especially superstars in the upper echelon of the genre), Bryan is known for writing the entirety of his catalog by himself.

This stands in stark contrast to the stereotype of three to five guys sitting in a room in Nashville writing shallow, homogenous “Bro-Country” songs for terrestrial Country radio. Zach Bryan has been so successful, with such a wildly different approach, that it necessitates quantifying this difference and contextualizing his position among his peers to fully appreciate what he has accomplished.

Leveraging Chartmetric, I created a dataset of ~20K Country songs and paired them with their lyrics to study trends in Country music lyrics over time. This particular analysis, which introduces methodology, key terms, and an overview of these lyrical trends, is Part 1 of a three-part series. Parts 2 and 3 home in on trends in Country music lyrics for individual artists and songwriters, respectively.

Methodology

To compile a large enough dataset from which to draw historical insights, I used the genre and sub-genre filters on Chartmetric’s Artists list to identify ~500 relevant past and present Country artists. This list includes legends George Jones, Hank Williams, and Willie Nelson; contemporary stars Morgan Wallen, Luke Combs, and Zach Bryan; and newer talents Bailey Zimmerman, Megan Moroney, and Conner Smith.

I then pulled discographies for every artist, which included each track’s release date, duration, current Spotify Popularity (0 – 100), and songwriters. Any song that did not have songwriters listed was omitted from the dataset, as this was a focal point of the analysis.

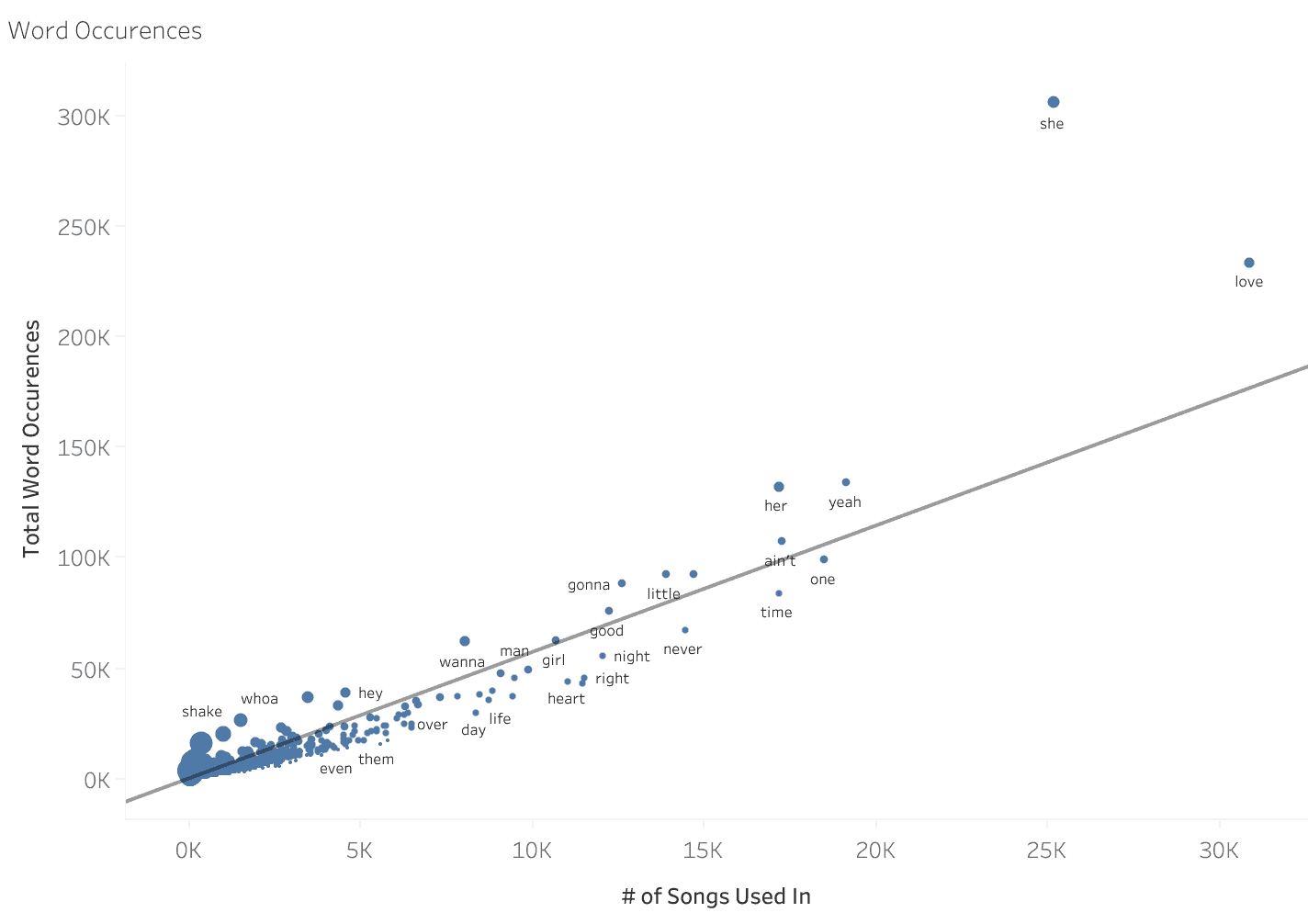

Upon gathering all of the necessary data points, I cleaned track lyrics of unwanted characters, identifying generic stop words that do not reflect the substance of the lyrics such as “I”, “a”, “you”, “is”, “me”, etc. Below is a plot of the most frequently used words based on total occurrences and number of unique songs (stop words omitted).

As expected, there is a strong relationship between the number of songs in which a word is mentioned and the number of total occurrences of that word in the dataset. The most frequently mentioned words, “she” and “love,” are reflective of the huge percentage of Country songs centered around personal relationships, and the other top lyrics are consistent with other studies of modern Country music lyrics (“little,” “yeah,” “ain’t,” “baby”).

Given the fact that research has already been performed by others on the most frequently used words and their association with stereotypical modern Country themes like alcohol, trucks, and women, this analysis focuses instead on metrics that reflect the song’s lyrical structure and word choices. Definitions for each metric used are below.

- Total Words: the number of words used in the song

- Unique Words: the number of words in the song with each unique word only counted once (if the word “little” was used five times, it was only counted once)

- Repetitiveness: the inverse ratio of unique words to total words

🧮1 – (unique words / total words)

- Completely Unique Words: number of words in the song that were used in that song alone and not in any of the other ~20K songs in the dataset

- Lyric Diversity Score: an aggregate measure of the uniqueness of words used in the song based on how many times each word occurs in the overall dataset (stop words excluded); higher scores indicate higher frequency of less common words

- Average Word Length: the average number of characters per word

Pairing these data points with the original track data, study began on how Country music lyrics and songwriting have changed over time.

Changes Over Time

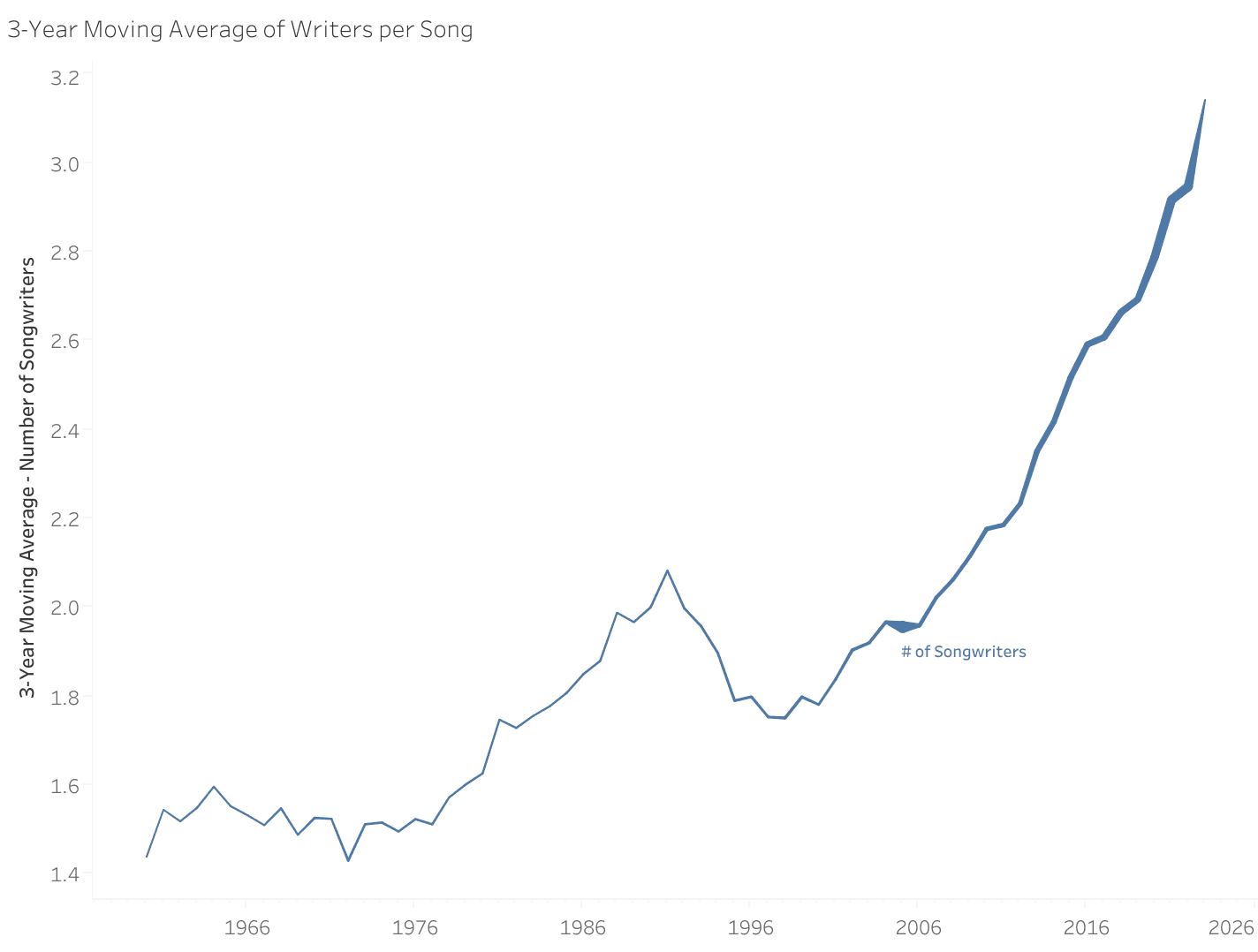

The first metric here is the average number of songwriters per track by year, starting in 1960 (the first year in the dataset with a significant number of songs).

This metric is represented as a three-year moving average to better showcase the trend over time, which illustrates a huge jump in this number starting at the turn of the millennium. In 2000, the average number of writers was 1.8 per song but it’s since jumped to 2.9 in 2022—an increase of more than 60 percent in just over two decades. That means, on average, Country songwriter teams have grown by one member in the last 22 years.

The trend line’s thickness reflects the number of songs in the dataset released in that year, indicating that there are more tracks in the dataset released after 2000. However, there are still enough tracks released between 1960 and 1999 to draw a strong conclusion that big songwriting teams are a relatively recent trend within Country music. The question then becomes how the growth in Country songwriter teams has impacted Country music lyrics in the 21st century.

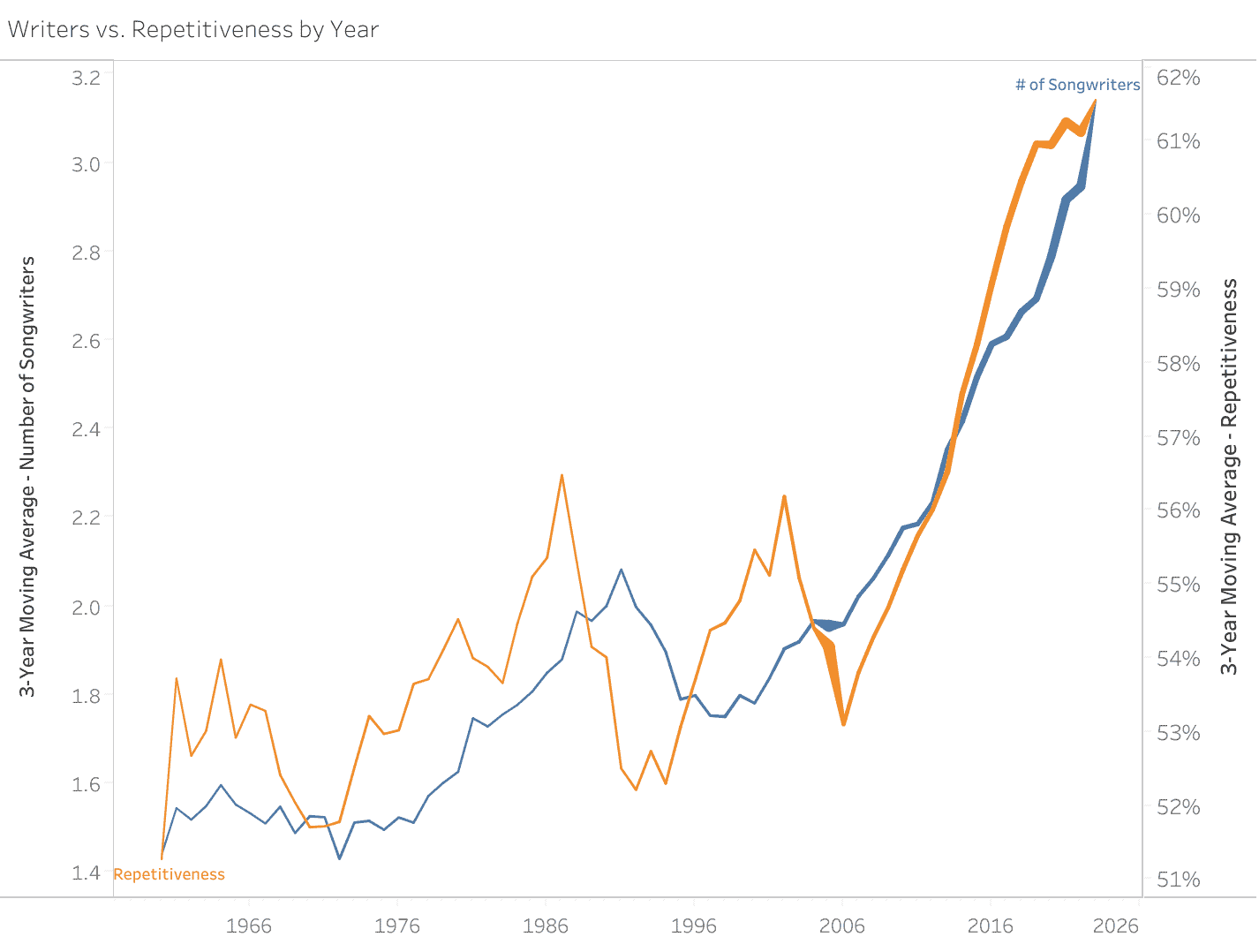

Adding the lyric repetitiveness metric to the same chart reveals an exceptionally similar trend to that of the average number of songwriters over the years. Shown above and once again displayed as a three-year moving average, the average repetitiveness has grown drastically each year since 2006. Starting at around 53 percent, it has climbed 8 percentage points to more than 61 percent in 2022.

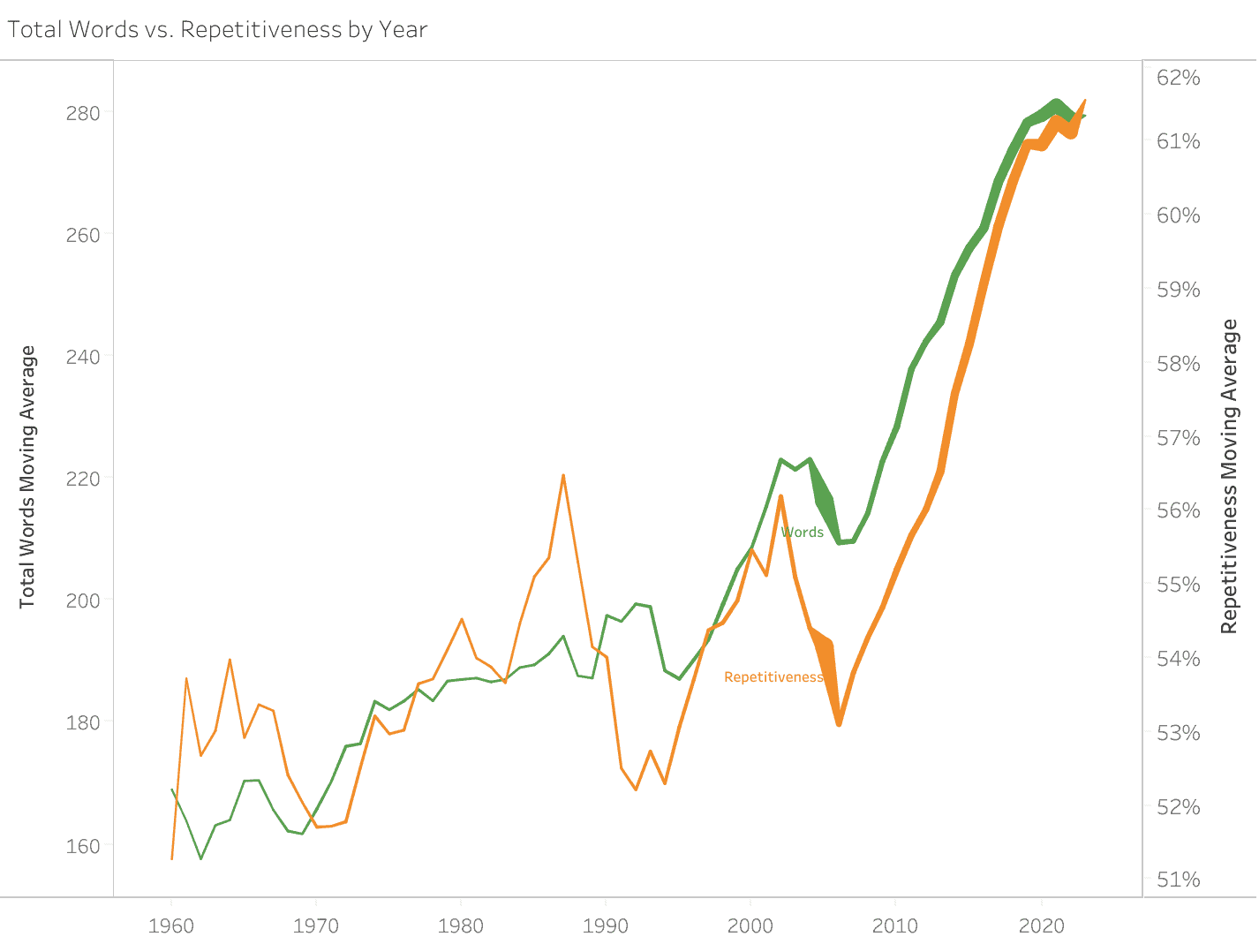

These mirroring trends hint at a relationship between the number of writers per song and the lyrical repetitiveness of those songs; however, there are additional factors at play. For one, the total number of words per song has increased over the years, which directly affects repetitiveness, or the inverse ratio of unique words to total words.

As the number of total words increases, repetitiveness also increases by nature of choruses and other refrains showing up more often in a song. This naturally decreases the ratio of unique words to total words, helping explain the increase in repetitiveness since 2005.

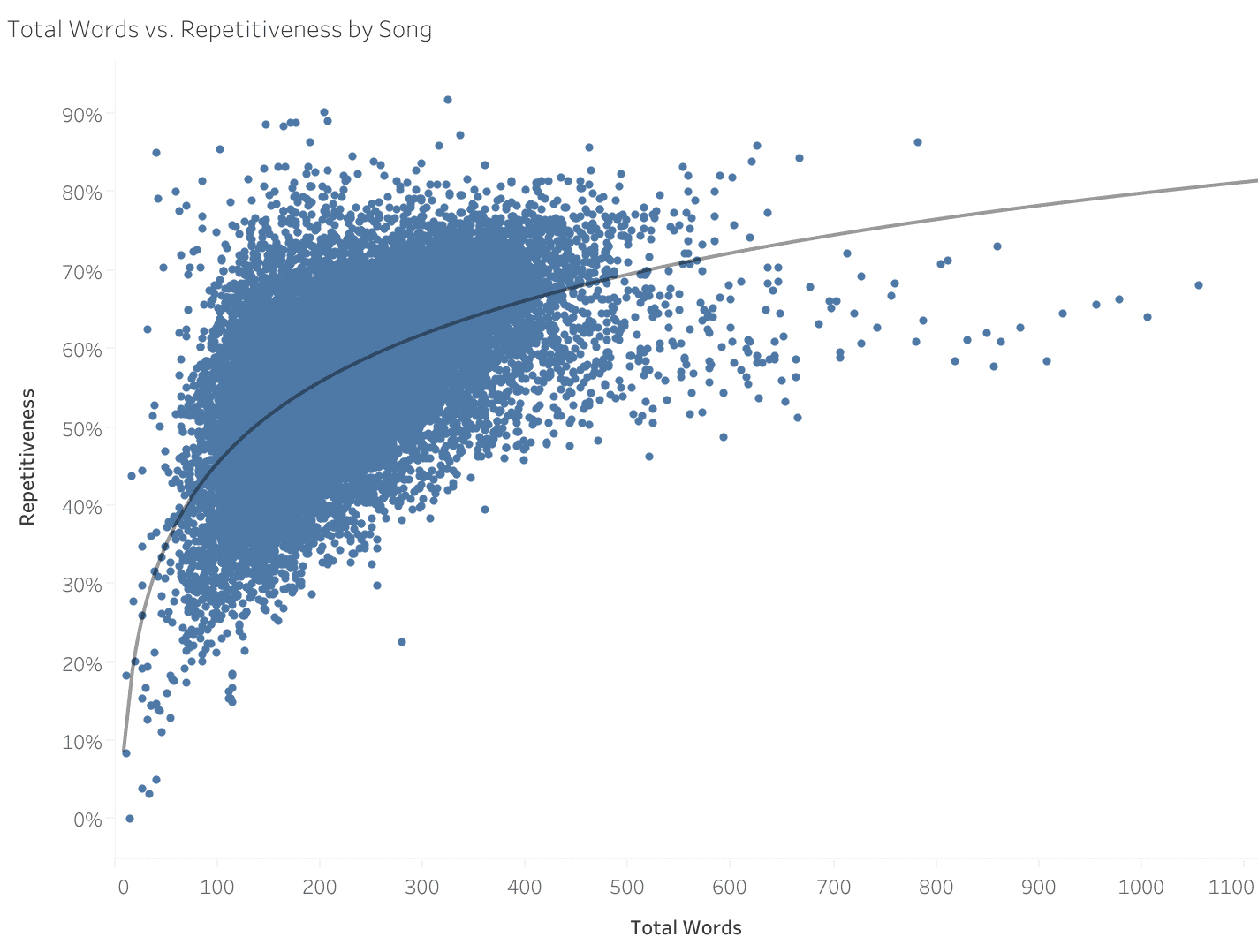

When plotting these metrics for each song in the dataset, a statistically significant positive logarithmic relationship appears (P-value < 0.0001) with an R-squared of 0.35.

These values indicate that the number of words in a song is a fairly strong predictor of its repetitiveness. However, that is not the only variable at play. As previously suspected, one of the other variables is the number of songwriters collaborating on a song.

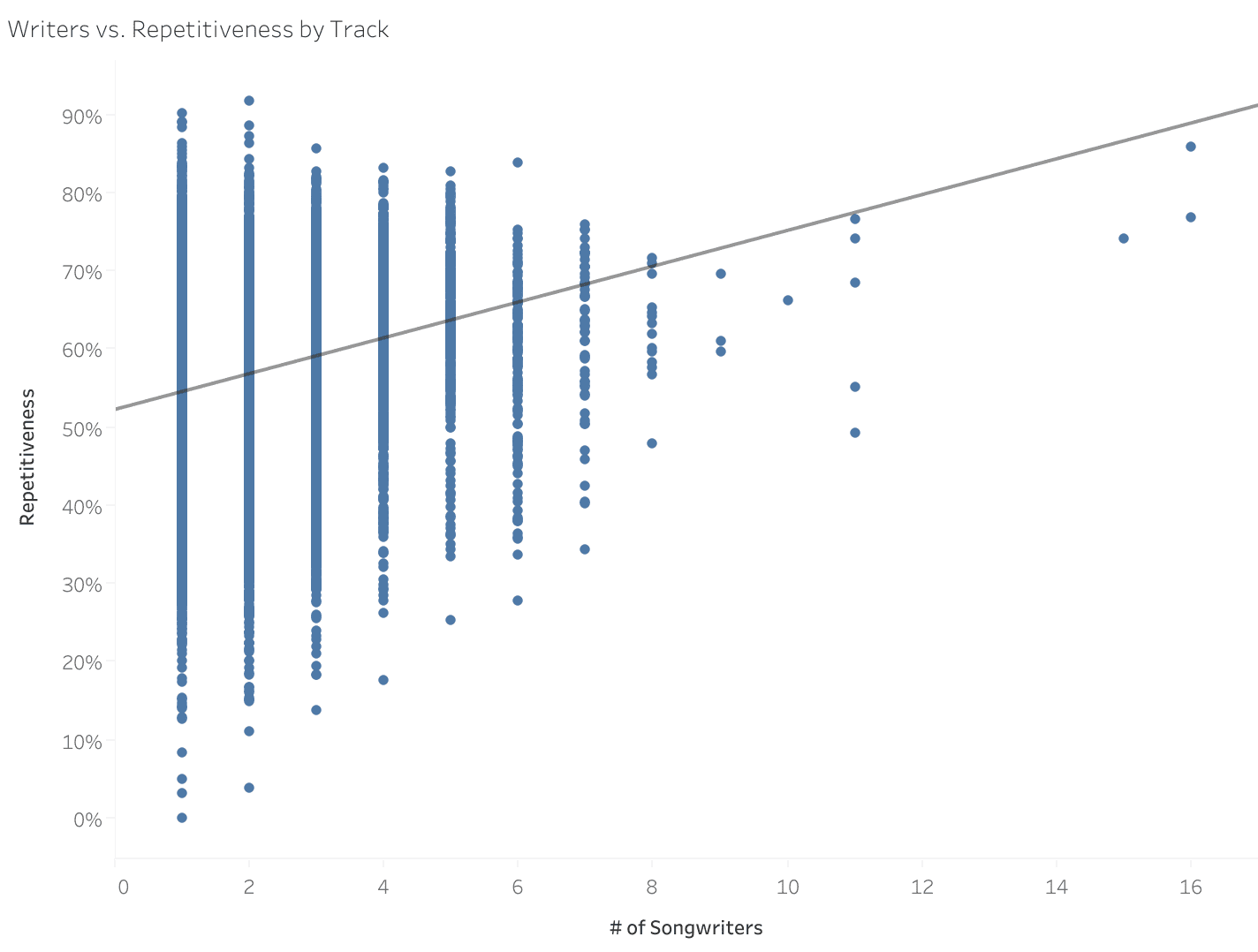

Albeit more nuanced of a relationship, you will notice that as the number of songwriters increases, the minimum repetitiveness also increases, as does the concentration of plots higher in repetitiveness. While less explanatory when compared to the number of words in the song, the number of songwriters is statistically significant (P-value < 0.0001). This indicates that there is an observed rise in repetitiveness as the number of songwriters increases. This relationship aligns with the trend seen within country music over the last 15-20 years.

The Storytelling Power of a Country Song

While more repetitiveness in a song is not inherently an indictment of its musical quality, this metric can be used as a proxy for storytelling. The more unique words there are in a song, the more likely a story is being told beyond the repetition of a catchy hook.

At its core, Country music has always been about storytelling. That is one of the anchors that differentiates the genre from other popular genres. The more repetitive Country music lyrics become, the more the lines blur between Country and Pop. Perhaps this is exactly what Zach Bryan was trying to avoid when he chose to sign with an organization that allows him to avoid big writing teams.

To that end, Parts 2 and 3 of this series will examine individual artists and songwriters like Zach Bryan to identify further trends in lyric metrics, songwriting teams, and popularity. Like anything else, there will always be the Zach Bryan example, the outlier and exception to the rule. As you’ll find out, these outliers provide fascinating case studies for further analysis.