Songwriter inflation adjustments must become mandatory

Songwriters are often not fairly compensated as it is, but inflation is just adding fuel to the fire. Here are a few suggestions to help fix this problem.

A guest post by Chris Castle of Music Tech Solutions.

[ALSO: Songwriters to protest at Spotify LA office: ‘music creators’ livelihoods hang in the balance’]

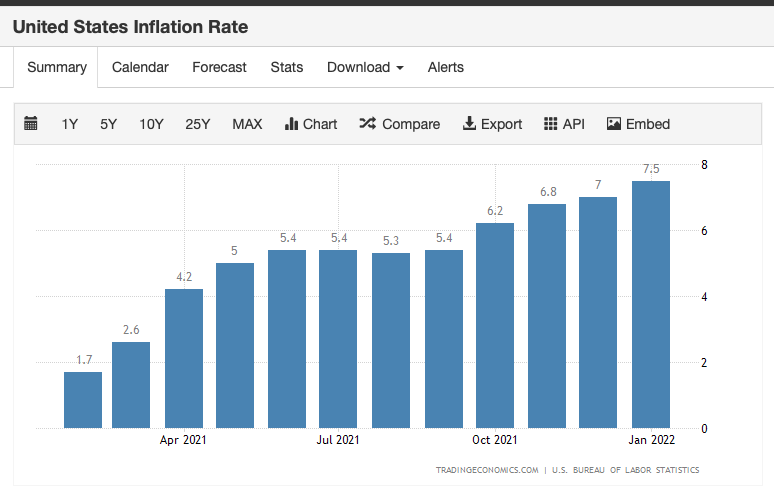

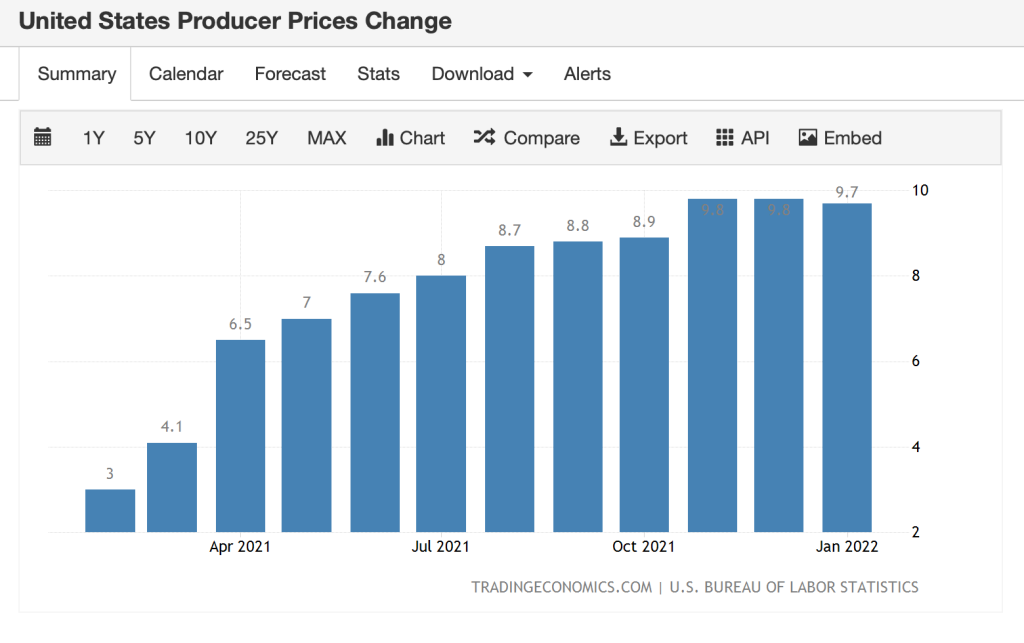

Both the consumer price index and the producer price index increased this month and the Federal Reserve is making noises like it intends to increase interest rates and reduce what is called the Fed’s “balance sheet”. Once again, the freeze on mechanical royalties for physical records like CDs and vinyl and failure to index to the consumer price index looks increasingly irresponsible if not downright antagonistic. If you agree that songwriters need to have a cost of living adjustment permanently built into all statutory rates, we have to also recognize that may be a heavy lift and needs to be supported by evidence. Here’s a few ideas.

Consumer Price Index

The next chart shows increases in the categories of goods that make up the CPI.

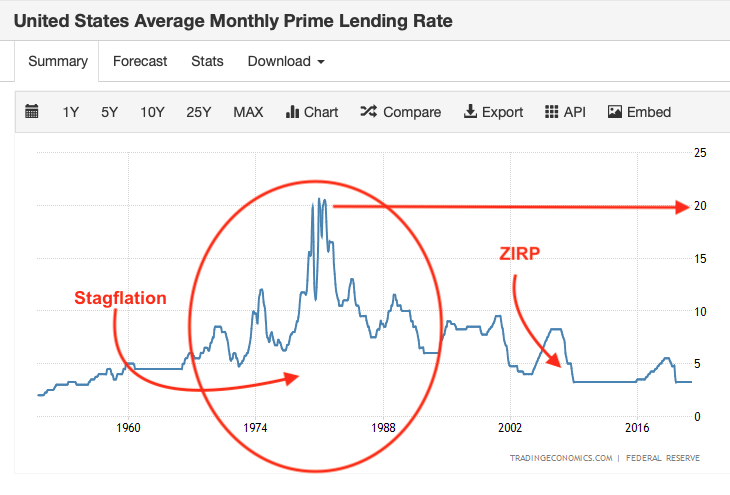

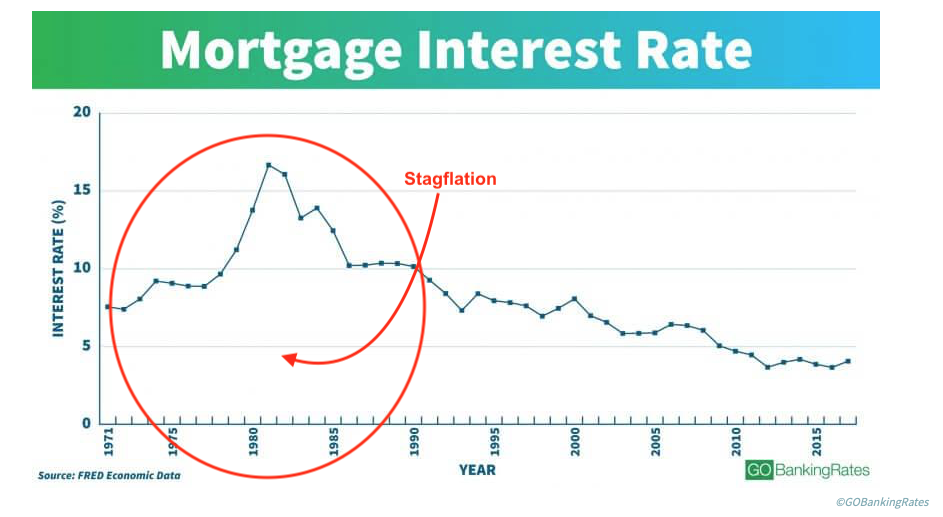

The January inflation rate is the highest since February 1982. If you don’t remember what was happening in February 1982, it was the end of the 1970s stagflation with supply side “exogenous” shocks to a number of sectors including energy. The other hallmark of the 1970s and early 1980s corresponding to the staglation is a black swan (we hope) increase in the prime rate of lending. The prime rate exceeded 20%.

One could say that the only reason that the prime rate is not much higher today is because the Federal Reserve adopted a zero interest rate policy (or “ZIRP”) in response to the 2008 financial crisis as did other central banks in other countries. The idea was that cheap money would encourage banks to make loans to borrowers as well as other banks and more debt would stimulate the economy. That’s why interest rates have been at or near zero for so long. (Not everyone thought this was a good idea, including me.) The truth is we don’t really know what interest rates would be absent the central banks’ distortion of the credit markets–perhaps for all the right reasons, but distortions nonetheless.

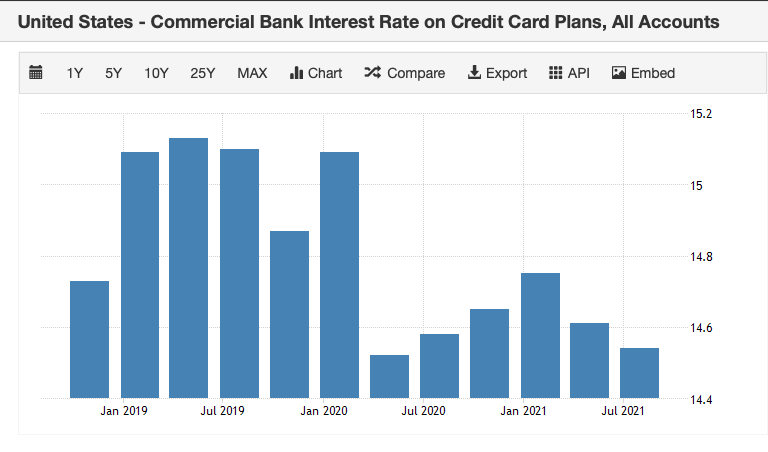

Increases in the 1970s prime rate caused all interest rates to increase, including credit card rates and mortgage rates. We are accustomed to seeing mortgage rates around 5% partly due to ZIRP, but mortgage rates were much higher in the 1970s. This caused a contraction in the number of people who could qualify for a mortgage and extremely high mortgage payments for those who could (not to mention “points” paid to compensate for the credit risk).

Remember the Federal Reserve’s mission is to use monetary policy to keep inflation under control and unemployment low. There are two policy “weapons” the Fed has to accomplish its mission: interest rates and the money supply. When the Fed adopts a ZIRP, what happens if those low rates don’t have the desired stimulus? That just leaves the money supply when zero interest rates lead to a “liquidity trap.”

With interest rates at their lower range (or “lower bound”) the Fed stimulated the money supply in a particular way called “quantitative easing” which involved increasing the money supply by creating money to buy treasury notes in a special way (not exactly printing money, but effectively similar) and also buying mortgage backed securities and other bonds in the open market. This was especially true in “busted offerings” when the government financed deficits with Treasury notes purchased by the Federal Reserve. And yes, that does sound rather hinky.

We’ll come back to that ZIRP policy and quantitative easing in another post, but let’s just say for now that the Federal Reserve provided more money to certain kinds of banks than they’d ever seen before in an effort to stimulate the economy without raising inflation. Yet they must have always known that an easy money policy was inflationary and due to ZIRP they had limited options–to kick the can down the road. Like a balloon payment in a mortgage, the devil would come for his due at some point. That time may be now.

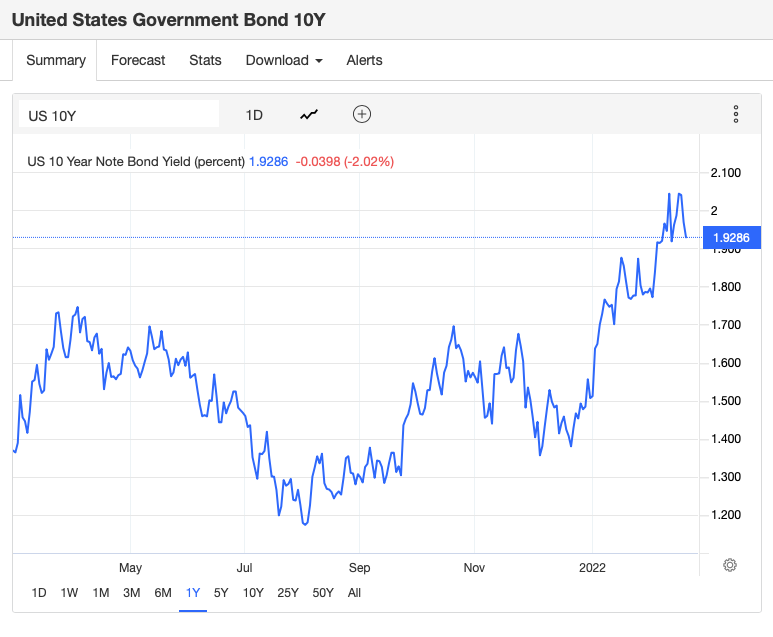

Whenever inflation goes up, there is an assumption–fueled by those who wish to avoid blame–that inflation is just transitory and will recede if the central banks take anti-inflation steps, such as raising interest rates by targeting even higher interest rates on Federal Funds (currently 0.25%) on top of an already higher 10 Year Treasury Bond.

If the Fed raises rates by .25% five times this year as projected by banks like Goldman Sachs, that will essentially double the interest payment on government bonds which fuels both federal spending and the national debt. The problem with that is the higher interest rates proposed by the central bank also affect government borrowing to service the $30 odd trillion dollar national debt. Maybe you can withstand your credit card rate increasing by five percent, but the government cannot.

As you can see from the charts above, some of this inflation is increasing at an increasing rate. It is going to take time to recede. Energy markets are fluid, for example, but rents are not. The conventional wisdom is that mortgage rates and home prices vary inversely to each other. Mortgage rates can also have an effect on rental prices, too; the harder it is to qualify for a mortgage, the more people have to rent, so rental prices go up. Rental prices are also sticky, meaning that once they go up, they don’t decline very rapidly or at all. Ask yourself the last time a landlord cut your rent?

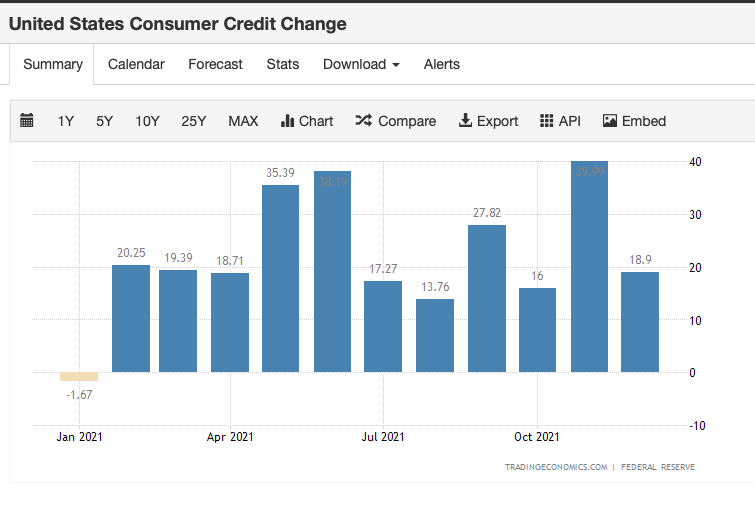

Speaking of the government’s credit card, it is important to look at the effect that inflation has on interest rates for another reason: many people have been dealing with the cost of inflation is by putting it on the credit card. Not everyone has a seven figure base salary.

Bands are prone to maxing out credit cards in the best of economic times so are likely to be especially hard hit just with increased interest payments on existing balances. This multiplier effect is important because on top of everything else the cost of inflation for people who have been putting it on the credit card is going to be many times worse than it is for people who have been paying cash. This is not something that you really wanna mess with, so if there’s any possible way and I mean any possible way you can either stop making it worse or start paying down that credit card do it because this is going to get very weird.

Producer Price Index

The Producer Price Index rose 1.9% in January to 9.7%. Remember, the PPI is a leading indicator of future inflation because producer prices foreshadow increases in future goods as lower priced inventories decline and price increases are in part passed through to consumers (or are in part absorbed by firms to sustain demand).

Inflation Expectations

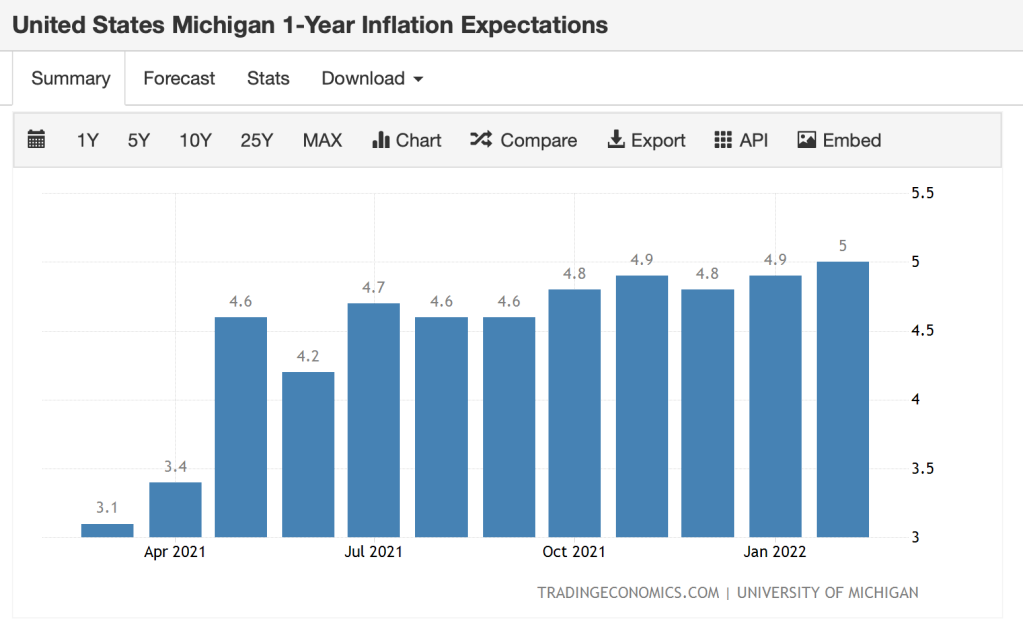

Should songwriters expect inflation rates will effect the statutory rates in the coming years? Remember that inflation expectations can have a direct effect on actual inflation because those expectations determine wages–if you think inflation will rise, you ask for higher wages. You see this on the interactive streaming mechanical rates (which recently were amended to include a cost of living adjustment), but for some reason not on the physical.

Determining inflation expectation requires survey data, and the benchmark surveys of consumer sentiment and inflation expectations are conducted by the University of Michigan. US inflation expectations for the next 12 months rose to 5% in February of 2022 from 4.9% in January. That is the highest level of 1-year Inflation expectations since July of 2008.

All this confirms again that inflation for the foreseeable future is not and will not be “transitory.” Statutory rates should be indexed to inflation for the foreseeable future. This should not even be a question (and was the rule in the latter half of the 1970s, and all of 80s and 90s). If the Copyright Royalty Board will not include a cost of living adjustment in all statutory rates, perhaps it should be imposed on them.