When do fans lose interest in discovering new music?

Part of growing up is developing an appreciation for the music around you. Discovery tends to start in the adolescent/preteen years. But over the last decade or so, music discovery patterns have been disrupted (like everything else).

We resurfaced this 2019 blog post because it explores the topic and the date behind it so well.

A guest post by Fred Jacobs of Jacobs Media Strategies.

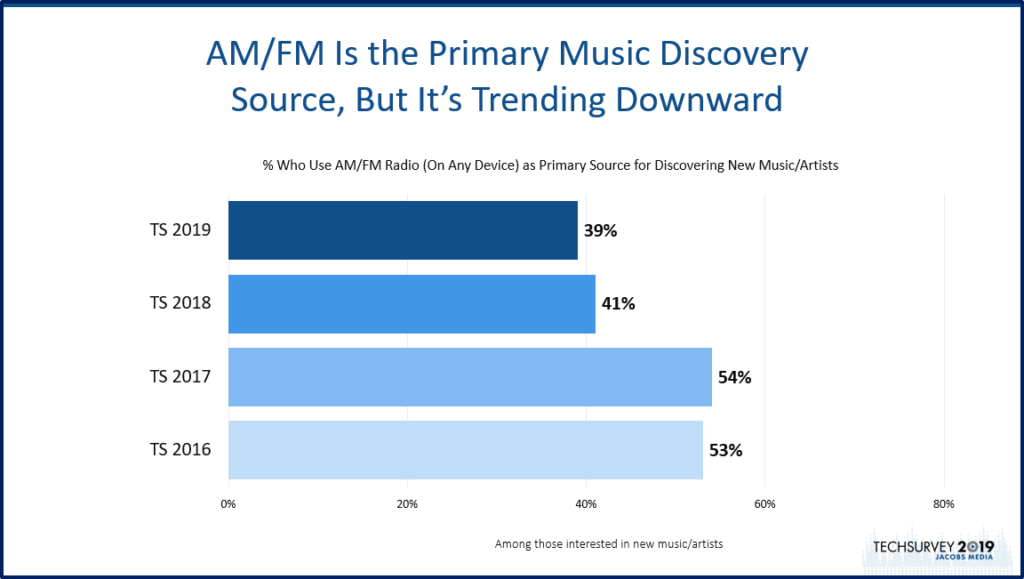

The chart below from Techsurvey 2019 depicted a declining environment for new music discovery on broadcast radio. To put things in perspective, the percentage for radio ticked down to 38% in 2020, and even further down in 2021 to 36%. So, the trend continues.

And we’re at a point with some radio formats where stations are playing less new music than ever. What does all of that say about the state of radio today. Or the state of the music industry today?

To get answers about the future, lets go back to the past for clues. – FJ

Believe it or not, I still have friends in the record label community, despite my lurid past as “The Classic Rock guy.”

And just about every conversation is another Kabuki dance about whether radio plays enough new music versus whether there’s any good music to play. It’s a chicken-egg thing. Stations are loath to play new music they don’t believe in. And labels won’t continue to discover, sign, and record artists that aren’t going to receive airplay.

Of course, I’m talking about the world of Rock music. With Country, Hip-hop, and other genres, it’s a totally different story as we saw the other night on the Grammy Awards show.

Like many rock programmers of a certain age, I vividly remember the days when we didn’t have enough current slots to accommodate all the great new music coming out. Scores and scores of artists had developed strong followings. The really good stuff by established groups had to get played – now. Cutting-edge stuff debuted at night or overnights. Everything else had to wait its turn.

The debut of a new album from Floyd, Journey, or AC/DC signaled their respective fan bases to come alive, often waiting in line at record stores to be among the first to buy it. The announcement of a new single by the Stones, U2, or Bob Seger actually helped stations “set occasions” that would have been powerful had PPM been around during those halcyon days of Album Oriented Rock radio – or as it was known as back then, AOR. As a PD, getting your hands on that new song – even a minute ahead of the competition – served as a little victory.

Back then, AOR excelled with 12-34 year-olds – the “sweept spot” of Baby Boomers. They were the target, long before the sweeping dictates of 25-54 buys clamped down on radio in the Eighties. They had money, interest, and enthusiasm for new music. And radio had their attention.

Obviously, this was a completely different universe than the Rock format finds itself in today. Everyone made a lot of money. And played a lot of new music because it was plentiful, and the audience demanded it.

Fast-forward to today. A research study conducted last year by Deezer, a streaming music company, reveals a condition they call “musical paralysis.” That’s when consumers lose their interest in new music.

Deezer interviewed 5,000 adults in the UK, the USA, Germany, France, and Brazil. And while the onset of “musical paralysis” varies considerably by country, the average fans hits the wall at around 28 years-old.

Covered in Digital Music News by Daniel Sanchez, the Deezer study shows that in America, most people’s peak music discovery period occurs when they’re 24½ years-old. But “paralysis” sets in around the time they reach they’re 30th birthday.

Interestingly, the top excuse for gravitating away from the new music scene is a lack of time, demanding jobs, and a sense of music overload.

Yet, there’s an important caveat. A majority of respondents – 60%, in fact – say they’d love to hear more new music if they just had more time.

So, where do consumers who have an interest in new music and new artists do their discovering?

Our Techsurveys tell an evolving story. Now, keep in mind that most respondents are radio listeners to begin with – mostly members of station email databases.

That said, there’s a pattern when we look back at the role broadcast radio plays in the discovery of new music. In our survey, radio is well ahead of other sources – satellite radio, streaming services, YouTube, and even friends and family. That’s the good news.

But its primacy over these other platforms is slipping. Just three years ago, a majority of Techsurvey respondents pointed to radio as their go-to source.

Here in our brand new, yet-to-be-released 2019 study, we see radio’s advantage is fading:

Part of the new music erosion radio may be experiencing could be emanating from the aging of the medium and its audience. And while no one is tracking this, chances are good that less new music is collectively being played since the dawn of the PPM Era.

But the Deezer study suggests something potentially interesting. If there was a way for a service, a platform, or a medium to efficiently expose audiences to new bands, new genres, and new releases – a clear, simple, and trustworthy curation process – you wonder whether there could be a “there there” for broadcast radio. Many stations also have credible personalities who can also provide much-needed guidance for the listening audience – new music Sherpas, if you will.

When it comes to “spins” and conventional exposure, many radio stations may not provide enough support to facilitate discovery. But given the growing on-demand nature of media consumption, broadcasters could be providing web and app tools and features that could make it seamless and easy for the harried, multi-tasking consumer to play catch-up with the new music scene.

It might also give radio brands a better chance to simply and inexpensively create web content that’s sticky, attractive, and marketable. The fact the Deezer points to lack of time, rather than lack of interest as the driver behind “musical paralysis” makes you wonder if the music industry world has slipped into the same type of jumbled overcrowded that has retarded podcasting’s growth.

Too much choice, too many sources, too many gadgets – and not enough time. Those are problems that someone really smart could solve.

Back when I was a programmer, you discovered new music from one or two local radio stations – and then you read about the artists in Rolling Stone. Today, discovery has become democratized – and that’s a good thing. But it has also become ubiquitous, scattered, and undependable, making the new music terrain overly abundant, confusing, and impossible for someone with a job, a family, or a life to navigate.

Radio performed a valuable service in the last century when American audiences coveted new music discovery.

Could it play a different – but very key role – in the new music environment today?

Fred Jacobs founded Jacobs Media in 1983, and quickly became known for the creation of the Classic Rock radio format. Jacobs Media has consistently walked the walk in the digital space, providing insights and guidance through its well-read national Techsurveys. In 2008, jacapps was launched – a mobile apps company that has designed and built more than 1,300 apps for both the Apple and Android platforms. In 2013, the DASH Conference was created – a mashup of radio and automotive, designed to foster better understanding of the “connected car” and its impact. Along with providing the creative and intellectual direction for the company, Fred consults many of Jacobs Media’s commercial and public radio clients, in addition to media brands looking to thrive in the rapidly changing tech environment. Fred was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame in 2018.