Mechanical rate freeze has led to inflation-induced decline in creator income

From an artist’s standpoint, it would be best mechanical rates increased with inflation, but that is not happening here. Read more to learn how inflation is changing the way artists are making money.

A guest post by Chris Castle of MusicTechSolutions

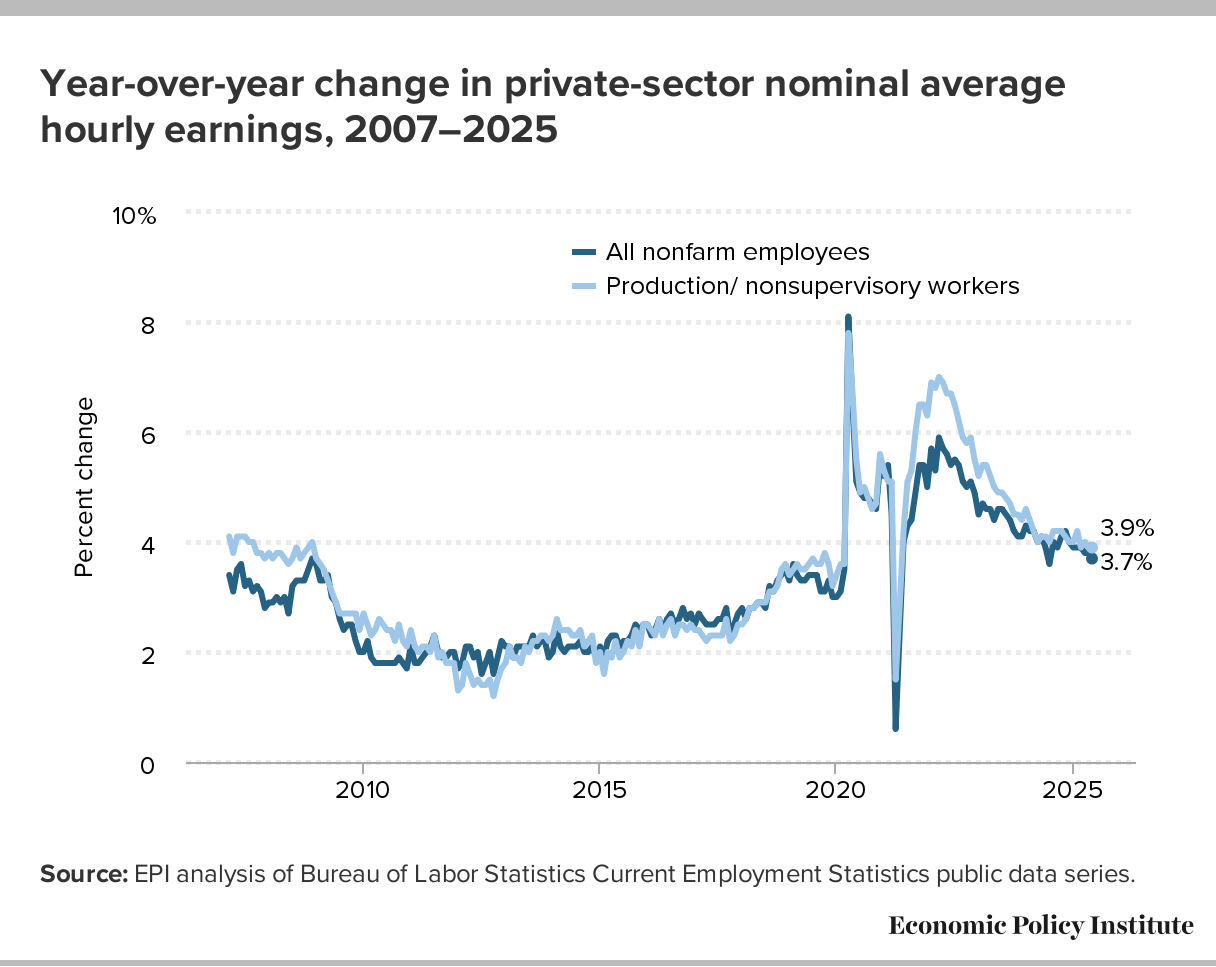

If you follow economics, you probably have heard the expressions “real wages” or “nominal wages” or “real” versus “nominal” wages. This isn’t a Cartesian metaphysical discussion–it’s about the effect of inflation on what they tell you you’re getting paid. Nowhere is this truer than with the statutory mechanical royalty rate. The rate will inevitably decline over time due to the rot and decay of inflation. Inflation is like having a cavity in your tooth that you don’t fix. It doesn’t go away. It may not hurt yet but it’s going to.

The effects of inflation are hardly a secret. Because of the effect of inflation on interest rates set by the Federal Reserve (who is charged with keeping inflation under control), vast numbers of people around the world keep watch on U.S. inflation rates as well as inflation rates in other countries.

For example, an hourly worker might be paid $12 an hour by her employer. That’s her “nominal wage” or “money wage.” But the issue is not what the worker is told they are getting paid, it’s what the worker can buy with her wages. What her nominal wage buys her is her “real wage” or her nominal wage adjusted by inflation during the same time period. Real wages are always less than nominal wages. This is why workers commonly get annual cost of living adjustments to nominal wages that increase their nominal wages based on inflation in addition to nominal performance-based increases. The same is true of entitlement payments like Social Security which just announced its biggest inflation adjustment in many years.

This is particularly important when understanding nominal and real statutory mechanical rates set by the government’s Copyright Royalty Board every five years. With a nominal wage (as opposed to a government rate freeze like a price control), there are a number of different countermeasures you can take in response to a wage freeze and take quickly. You can always try to negotiate a higher hourly or annual wage if you are falling short of inflation. You can also try to quit and find another job that pays more money. Perhaps even get an annual raise built into your salary.

However, with the statutory mechanical royalty, there is no escape. Songwriters are at the mercy of both the government (in the form of the Copyright Royalty Board) and the people who are supposed to be negotiating for them who seem to have decided that millions of songwriters don’t need a cost of living adjustment. Without “indexing” the statutory mechanical to inflation (meaning a CRB ruling requiring automatic cost of living increases based on increases of inflation), songwriters’ buying power actually decreases over time. That’s the difference between the nominal mechanical royalty and the real rate, i.e., the inflation adjusted rate.

Nowhere is this more apparent than with the “frozen mechanical” that you’ve probably heard a lot about if you’re a regular reader. It’s called “frozen” because the rate for physical and vinyl was set by the CRB in 2006 and has not been raised since–apparently at the request or acquiescence of those negotiating in the songwriters’ interest. Think about that–remember what happened in 2008 (just a couple years after the rate was frozen)? The Great Recession aka The Big Short.

It may not be obvious to you but most of the laws in the US are not passed in Congress and they are not signed by the President. The overwhelming majority of these laws are created by administrative agencies, often located in the Executive Branch, but not always. When it comes to songwriters there is a federal agency that has almost total control over certain aspects of your life.

That agency is the Copyright Royalty Board which has three “judges” that are appointed by the Librarian of Congress (therefore are in the Legislative Branch of government along with Congress). While these members of the Copyright Royalty Board are styled “judges” they are not “all purpose” judges appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate (under Article III of the Constitution for those reading along at home). (This CRB appointment issue is a matter of some debate but we will talk about the appointment issue some other time (attention Justice Kavanaugh).)

Whether you know it or not or like it or not you have delegated your personal agency to the CRB and you have also delegated your agency to the people who can afford to appear before the CRB. This is the classic case of the merger of the little intellectual elite in a far-distant capitol who think they can plan your life better than you can. If you have no idea about the CRB, there’s an easy answer–you’re very unlikely to ever wander into a CRB hearing because the hearings take place in the Library of Congress which is not someplace that songwriters typically are found. Even so, you have delegated your authority whether you know it or not and whether you like it or not to certain representatives of the music publishing community who act on your behalf and probably without your direct authorization. There’s plenty of blame to go around. To paraphrase Lord Byron, if you want a friend in Washington get a dog. Preferably a big one with teeth.

Here’s an example. According to government data, 9.1¢ in 2006 is worth approximately 13¢ today, or approximately a 33% inflation rate. That means that the frozen 9.1¢ rate in 2006 has the buying power of approximately 6¢ in 2021. In other words, the real mechanical rate has actually declined although the nominal rate has stayed the same. Why? Because like King Canute commanding the ocean, the nominal rate was not increased to at least stay even with inflation and inflation rotted it from the inside out.

So you can see that when you’re considering the mechanical rate that is set every five years by Copyright Royalty Board, the rate that matters is the real rate. However, the CRB only set a nominal rate for songwriters in 2006 even though they could have increased that nominal rate based on increases in the consumer price index. They could also have increased the rate in Phonorecords II or Phonorecords III but did not.

And now 15 years later, the frozen mechanicals crisis has been engaged by a revolt of the songwriters in Phonorecords IV, currently before the CRB. The struggle is all about real vs. nominal mechanical rates.