How Spotify royalties actually work

While many in the music community believe that Spotify royalties should be larger, the specifics of how they are calculated aren’t always well understood. Here, we clear the fog.

Guest post by Juan C Sarassa from Key of B#

Recently there’s been a lot of chatter about songwriters’ battle, represented by the National Music Publishers’ Association (NMPA), with Spotify over the negotiations with the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB). Spotify has proposed a lower payment for songwriting royalties which as understandably upset the songwriting community. However, I thought it would be good to write this article with a detailed explanation of how Streaming payouts work and who is getting what, so that we, as the music industry, can better understand how we can improve the remuneration for artists, songwriters, and producers.

Down to basics

First of all, it’s important to understand the underlying legal framework that allows artists and songwriters to get paid, and that’s Copyright law. In music, there are two separate copyrightable assets when we stream a song and that’s the musical composition, a.k.a. the song, and the sound recording, a.k.a. the master.

There’s also a series of exclusive rights that comes with the ownership of a copyright that includes making copies, known as the mechanical right, and performing the work to the public. When we talk about mechanicals, these are royalties paid to the songwriter and their publisher for the right to create individual copies. For example, every time a label manufactures a CD, they must pay the songwriters of all the songs a royalty for every single copy they make of said CD. In the US this rate is statutory, meaning that in the US Congress sets it, while in UK it’s a percentage of the price of sale. On the songwriting side, it was decided that a stream was a combination of a mechanical use and a public performance. This means that your Performance Rights Organization collects your income from Spotify on account of the songwriting payments.

On the Sound Recording side, Spotify pays the master’s rightsholder a license to use that recording on their service. We’ll dive deeper into how this works in a second. So, to sum up, there’s technically 3 payments involved in streaming, one mechanical, one public performance (both to the songwriter) and one to the sound recording rightsholder.

Now what’s all this rightsholder stuff we’re talking about? The rightsholder is the owner of a master recording. As you may know, usually when an artist signs with a record label, they give the label ownership of all their recordings in exchange for money to finance these productions. Because of this, most of the revenue from these master licenses goes to these labels, and the artist receives a negotiated percentage which usually ranges from 15-20%. When you stream music made by an artist signed to a major, Spotify pays the label directly, and then they distribute the money or count it towards the artist’s recoupment of any money they owe. If it’s an independent artist and they own their masters, the payment will go to their distributor and they will pass on the money to the artist, minus whatever fees they charge.

The Current Situation

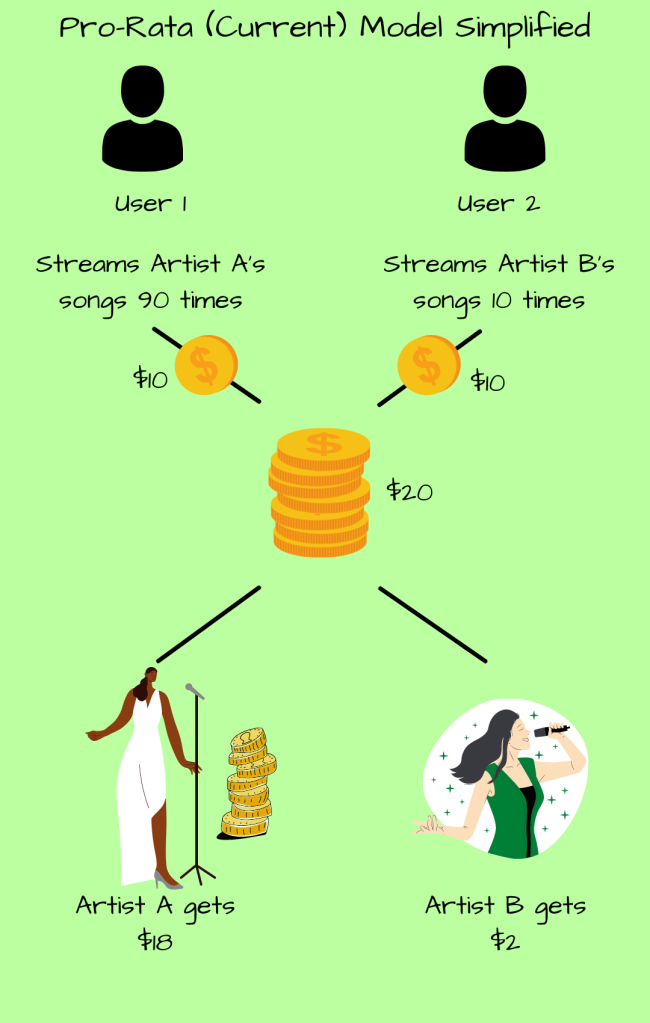

Now let’s get into it. The deal is that Spotify pays 75% of their total revenue to songwriters, publishers, and sound recording owners. 15.1% goes to songwriters and publishers, and the other 59.9% going to sound recording owners. The way they distribute these royalties is by adding up the total amount of streams and dividing it by the percentage of the revenue they agreed to pay out, resulting in a payment per-stream. This amount is then multiplied by the times a specific recording has been streamed and pays that amount to the corresponding party. This is called the “pro-rata” model.

However, this pooling of money isn’t global, they pile it up depending on the location of the stream, since every country has a different subscription fee. They also separate streams from paid subscriptions from the ad-supported accounts; streams from the paid subscriptions pay out higher royalties than the ones from free accounts. This makes it very difficult to calculate the exact number of royalties per-stream, and if you already have songs up on Spotify, you’ll see that every stream has a different rate.

As we know, the pro-rata model yields extremely low per-stream payments for everyone involved, especially artists signed to major labels. However, the majors have so many artists under their wing that they will rack up most of the streams on the services, making it profitable for them. This model makes you, an emerging artist, compete in the same pond against the biggest acts in the world for the same pennies. These big artists will also make a good amount of income through streaming due to the sheer volume of listeners they have.

Alternative Proposals

This pro-rata model seems to be the standard for streaming services, although SoundCloud and Deezer are testing a solution. They call it UCPS, or User Centric Payment System. How this works is that instead of pooling the money from all subscriptions, they divide the user’s streaming record over their actual subscription amount. In essence, if you pay $10, Deezer will keep $2.5 for themselves, and pay out the other $7.5 proportionally to the music you streamed. That means that in theory, if you only listened to a single artist, they’d get the whole $7.5 in their pocket. This sounds fairer, and arguably it is, but the trials that have run show that the difference isn’t much when considering the average user’s listening habits.

For more information on the impact of UCPS on actual streams, make sure to check out the study made by Centre Nacional de Musique.

So, now what?

In conclusion, the problem for emerging artists with streaming is that they are small fish in the largest pond there could possibly be. Because of this, artists need to become flexible and look for alternate strategies to monetize and profit from their careers, because it doesn’t look like streaming income is going to significantly rise any time soon; there is actually no more money to be paid since most services aren’t even profitable yet. However, I do call on Spotify, Amazon, Apple Music, and all other DSPs to be transparent on how exactly their payments are made. Currently, Spotify only has a vague article explaining the basics, but artists deserve to know the exact figures to make sure we keep them accountable!

For more information on how to monetize your music career, make sure you check out last week’s post on how to do just that.

Spotify royalties are paid out of the net revenue generated by advertising. Artists are paid on a monthly basis. When Spotify pays artists, they add up the total amount of streams for each of their tracks and figure out who owns and distributes each one. take my online class for me