What happened to all the chords?

Here, Ben Morss explores in detail why songs featuring multiple chord progressions have become such a rarity in today’s Top 40 songs, with single-progression tracks now largely ruling the roost .

Guest post by Ben Morss of Soundfly’s Flypaper

This article originally appeared on Ben Morss’ Rock Theory blog.

Single-Progression Songs

These days, a typical Top 40 song is built on a single chord progression. By this, I mean that the same pattern of chords repeats from the beginning of the song until its end. For convenience, let’s call songs like this “single-progression.” Songs in which the chord progression changes significantly, we’ll call “multi-progression.” (This is why I get the big bucks.)

The point is, multi-progression songs have become rare — and I miss them. When did multi-progression songs fade away?

I haven’t discovered a proper study chronicling the change, but I believe it happened in the early 1990s, as alternative rock and gangsta rap moved into the U.S. Top 40.

In the 1980s, the hit parade included numerous songs that were packed with chords — like “Total Eclipse of the Heart” and “Automatic” — alongside single-progression songs like “Born in the U.S.A.” and “When Doves Cry.” By the mid-1990s though, the emphasis had shifted to songs with fewer chords, often single-progression songs, like “Gangsta’s Paradise” and “Steal My Sunshine.”

Though of course you can create a fantastic pop song with just one chord progression, I do think the ability to change chords is a vital element in the songwriter’s toolbox. Without it, some songs fall flat.

And so I want to talk about a song from the 1980s, where a subtle tonal shift for the chorus is a vital part of the song’s magic. And about a single-progression song from the 2010s which, I fear… ends up falling flat.

The Day the Chords Went Away

First, though why did this change? It helps to note that this chord density decrease occurred in hip-hop, pop, and rock, in parallel.

Hip-Hop

Rap songs are generally built around a single sample which repeats during most of the song, as additional layers are added or removed. This way of working limits the ability to change to a new chord progression. While of course, the song could change to a new sample in the chorus, or change the chords by changing the bass, this is not generally characteristic of a style which originated with an MC rapping over a breakbeat. (Though there are notable exceptions, such as the music of Kendrick Lamar.)

Pop

In the 1990s, as the sounds and attitude of hip-hop permeated the Top 40, so did hip-hop’s way of building a song around a sample (“I’ll Be Missing You”). Even producers and songwriters who didn’t use samples often built songs around an instrumental riff that was treated and repeated like a sample, like “Are You That Somebody” and “No Scrubs.”

Producers also now created songs on computers instead of recording them to tape, making it possible to tweak sounds endlessly and layer tracks with abandon, and they became more interested in exploring this vast new potential than in getting creative with harmony.

Historically, songwriters distinguished the bridge section by exploring a new tonal area — but now they could achieve clear textural variety (and a bit of street cred) by bringing in a rapper. And this sample-based and sound-based way of working extended to non-hip-hop-influenced music as well.

In 1997, The Verve’s international hit “Bitter Sweet Symphony” was based around a sample of, of all things, an orchestral version of the Rolling Stones’ “The Last Time.” (After a legal battle, royalties from this international hit ended up going to Allan Klein, Rolling Stones’ former manager.)

Rock n’ Roll

In 1991, Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and the Seattle sound burst onto the charts and changed commercial rock forever. Suddenly, rock musicians who wanted to be commercial had to sound raw and unschooled. Loud guitars were in. Vocal harmonies and flowery melodies were out, and so were songs with lots of chords.

In particular, the songs on Nirvana’s Nevermind tend to have the same chords in the verse and the chorus. Borrowing from The Pixies, Kurt simply stomped on the distortion pedal in the chorus, making it bigger by making it loud. Fortunately, his melodies were quite inventive. With a loud chorus and contrasting melody that uncovered new relationships in the chord progression, who needed new chords?

The chorus and verse of “Smells like Teen Spirit” are so different that you’d never guess they shared a chord progression.

I wish I knew more about two other genres that were popular in the U.S. — country music and electronic dance music — but as far as I can tell, neither of these genres has typically been known for complex chord progressions either. (“Achy Breaky Heart,” anyone?)

Anyway, since the shift hit multiple genres around the same time, I’d speculate that its causes transcended any particular style of music. Instead I’d look to broader technological and cultural changes:

- An explosion of digital technology gave musicians and producers much more control, giving them vast freedom to innovate with sounds, beats, and layers of tracks. Artists explored new sounds and rhythms at the expense of chords and song structure.

- A cultural shift encouraged pop songs to sound less artificial. Instead, pop was supposed to reflect a more raw and authentic expression of an artist’s true emotional state, even if in fact months of production was secretly used to get there. This mirrored similar shifts in cable TV, movies, and other areas of popular culture.

“West End Girls” (1984)

A Song With an Unusual Hook

As you can probably tell, I’ve been thinking about all these things for a while. But I had occasion to think about them all over again while listening recently to the Pet Shop Boys’ “West End Girls” on a phone. Over the phone’s tinny speakers, the chords in the verse and the chorus sounded really similar. They’re played on a synth string patch that obscures the actual pitches, and I had to put on headphones to hear the bass, at which point it was clear that the chorus chords are subtly but significantly different.

But I could now imagine a world where the bass didn’t shift up in the chorus — where “West End Girls,” like a post-1990s song, didn’t change progressions at all. What would have been lost?

“West End Girls” would be a compelling song in any case. It entices the ear with its smooth, world-weary attitude, its calmly intense vocals triumphing over a mid-1980s dance pop instrumentation that would normally be desperately cheesy. Apparently the song was influenced by T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” and the line “From Lake Geneva to the Finland station” apparently refers to the journey Lenin took to escape to Russia. It’s apparently the only #1 pop hit written by a music critic. And recently The Guardian decided “West End Girls” was the greatest UK #1 single of all time. What’s not to like?

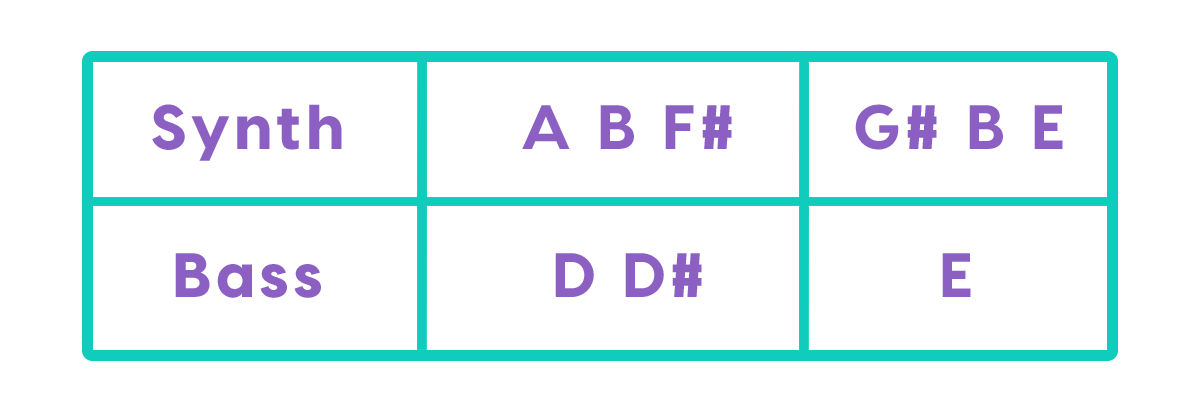

Of course, as a music nerd, I was more enthralled by the song’s striking instrumental hook, in which a synth bass climbs up D-D#-E, articulating a shift from B7 to E major:

It’s a simple, yet potent take on a classic V7-I progression. When the D is played, we feel briefly like we’re in a Bmi7 chord in first inversion. When the D# is played, we’re in a B7 in first inversion. Then, before the ear can quite assimilate what’s happened, we’ve arrived at E major.

Since the D is on a strong beat, and the D# on a weak one, the rhythm emphasizes the minor flavor of the V chord, treating the more harmonically significant major flavor as a passing tone. The really cool thing is that the verse was in E minor, and the hook emphasizes the minor form of the dominant — so when the hook smoothly and subtly shifts us to E major, it sounds magical, the revelation of a quiet mystery.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “How to Use 7th Chords in 7 Minutes.”

The Verse and the Chorus

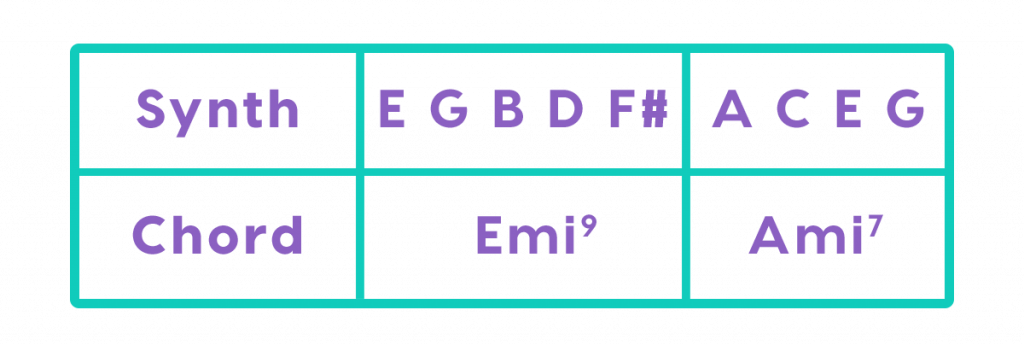

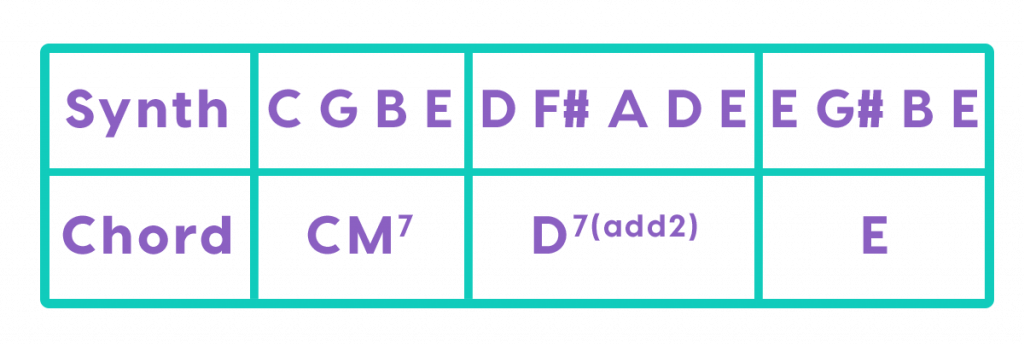

Now let’s look at that verse. Here, Neil Tennant raps over two repeated chords:

The ’80s synth string sound makes it hard to distinguish the pitches. I can’t actually detect whether the first chord contains a G. Since Tennant described this chord as a “G major 7th with an E bass,” I’ll include the G, but the chord quality isn’t strongly affected by its presence or absence. We readily recognize this as an Emi9-Ami7 progression.

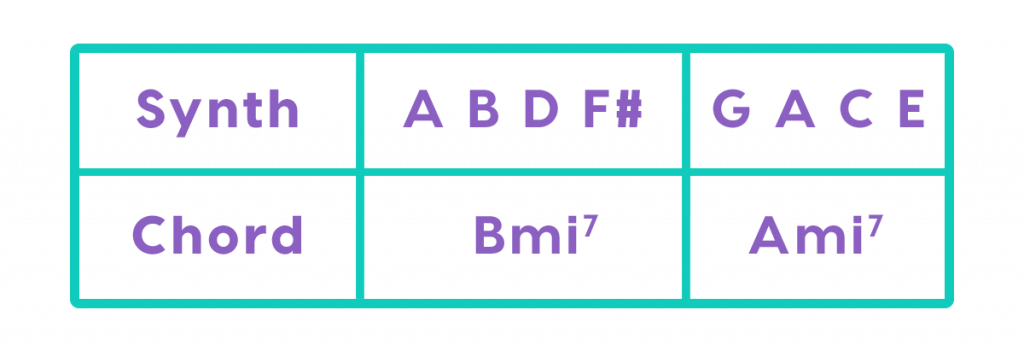

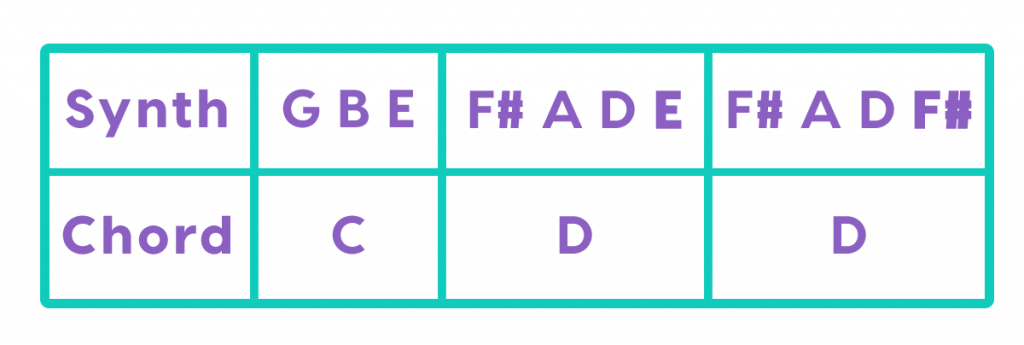

To me, in this song, the jazz pitches included in each chord soften its minor quality, lending the song a cool, thoughtful, gently Romantic quality, always opening out as it moves up from i to iv and back. The chorus chords are a subtle shift from the verse:

The move to Bmi at the start of the chorus is barely detectable. Without the bass, and with the blurry strings synth patch, you’d think you were still in the verse. There’s no change in the arrangement, except that Tennant starts to sing. And as we’re still in the same key area as the verse, the melody he sings would match just as well with the verse’s Emi9-Ami7 progression as it does with the Bmi7-Ami7 progression they actually used.

A Harmonic Journey

So, what if this song had been written in 2020?

It might well have used the same chords in the chorus. Here’s how the end of the verse and the start of the chorus would sound:

This sounds completely acceptable. And no doubt a modern pop producer would do all sorts of interesting things to the arrangement and the vocals to give the chorus the lift it needs. But compare this to the song played with the actual chords:

It’s subtle, but functionally quite different. As Tennant says, the chorus is the part where the track “moved up.” Instead of sticking with the verse’s i-iv progression, it rises to a v-iv progression. This lends it a new energy; it lifts the song up. The chorus rises to v, and throughout the section, we wait for the chords to sink back down to a i or I chord.

In other words, we’ve created tension, and the ear expects a resolution.

The cool thing is that the resolution, the return to i, happens through the song’s main hook. Magically, the hook provides the resolution we’ve been waiting for, suffusing it with meaning, energy, and satisfaction. In other words, instead of the song just shifting to E major for variety, it returns simultaneously with the resolution, with the return to I. This is a potent moment, giving the hook much more meaning than it would have in isolation. And it’s where we drop the title of the song as well.

That’s songwriting, folks!

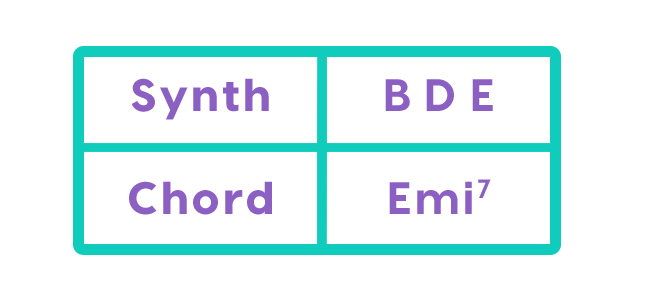

Expanding our horizon to the entire song uncovers an even larger harmonic journey. The song begins with sounds of the street, to which it adds a long Emi7 chord:

Then, at 0:19, the following chords come in.

This starting chord, plus the opening CM7-D-E progression, introduce the idea of a shift from the realm of E minor to E major. (Not only do we start in E minor, but the CM7 comes from the minor tonality.) It’s a microcosm of the entire harmonic journey of the verse and chorus.

To me, it feels like an expansion of the hook progression; still three chords, still rising, still ending in the same place, but happening twice as slowly (half notes instead of quarter notes) and covering twice the distance (two whole steps instead of two half steps).

At 0:37, we hear the hook, which leads directly into the main song. But just before that, the song does something I think is really cool, something we seldom see in pop songs, but which can help a pop song rise to the level of classical music. It abandons the repeated progression in order to create a stronger moment of tension and release.

We hear the CM7, then a D that’s a bit different than the one we’ve been hearing:

Yes, the D chord ultimately switches its top note to an F#. And then… we wait. The last D is held for six beats. Finally we hear the third chord of the progression, the E — but it comes in via that hook. Here’s how the whole thing looks and sounds:

This adds a bit of bonus tension, prolongs it, and once again resolves it through the hook.

Ultimately, the opening CM7-D-E progression doesn’t return until the outro. It bookends the song, creating a harmonic journey that spans its entire duration.

“West End Girls” would be special even without these few extra chords, the little twist here and there. But these elements combine to create a macroscopic harmonic journey of the sort we don’t always hear in pop. They lend the song a larger meaning. This is what makes a song something worth hearing many times, instead of something catchy that grabs you but soon wears out its welcome. It makes the song more timeless.

Now, let’s compare this to a single-progression song created after the great 1990s divide.

“Cake by the Ocean” (2015)

While thinking about “West End Girls,” I started also thinking about DNCE’s 2015 Top 10 hit “Cake by the Ocean.” At first I had no idea why, since the songs seem different on the surface. But a quick look reveals deep similarities.

How the “Cake” Is Baked

“Cake by the Ocean” is a single-progression song. The progression in question is Emi-Bmi-Ami (not unlike the Emi-Ami of “West End Girls”). The chorus melody of “Cake” features a D over the Emi and an A over the Bmi, which makes the chords feel more like Emi7-Bmi7-Ami, close to the Emi9 and Ami7 of “Girls.”

And, okay, even though I don’t personally hear sevenths played in the keyboard or guitar parts, it feels to me as if the chords in the chorus have sevenths — as in, I feel like I hear Emi7-Bmi7-Ami7. Nor am I the only one who feels this way; this official piano sheet music contains the sevenths as well.

“Cake” has distinct sections: an intro, verses, prechoruses, choruses, a breakdown, and an outro. And yet the chord progression never changes. Instead, “Cake” demarcates its sections and achieves variety using the tune and the arrangement. Here’s how that works, from the intro through the first chorus:

- Intro (0:00) — minimal arrangement, just the song’s main guitar riff accompanied by handclaps.

- Verse (0:08) — voice, main guitar riff, plus basic drum kit. The melody moves at a moderate speed, featuring mostly consonant pitches like the 1st and 5th scale degrees (for example, E and B over the Emi chord). It repeats the same pattern three times, followed by an ending tag that repeats the pattern’s last two pitches.

- Prechorus (0:24) — the arrangement intensifies, adding a guitar playing offbeat chords and throwing in bits of backup vocals. The melody consists entirely of low A’s, except that the very last note descends to a G. The melody moves much faster, though, contributing to the intensification. To build further suspense, for the last two measures, the beat drops out completely.

- Chorus (0:40) — Party! The song pulls out all the stops to shout, “Hey, this is a chorus!” The tune rises more than an octave, featuring catchy multi-tracked high falsetto vocals, transposing the consonant E-B of the verse up a full seventh to a high and dissonant D-A.

The arrangement adds more percussion. The guitar rhythm is more elaborate and more present. There are sound effects, plus maybe some subtle keyboard pads.

To me, the song’s main task is to set up the chorus for maximum impact, using every nonharmonic trick in the book. The verse melody is simple and forgettable, with a basic arrangement. The prechorus melody is deliberately low and monotonous. So when the chorus roars in, it’s a big moment. And it is a fabulous chorus, a classic summer hit!

Next, we have a second verse, prechorus, and bridge. The second verse adds a new guitar riff. The second chorus adds even more subtle tracks and sounds, and even a cute little “oo-aha” tunelet. But there’s no significant new harmonic, textural, or lyrical material. Unfortunately, the song is now out of things to say, but it’s still got two minutes and twenty-three seconds to say that in. “Cake” is running out of steam!

Running Out of Steam

But there’s one more chance. After the second chorus, traditionally, we might reasonably expect there to be a bridge. For multi-progression songs, this is an opportunity to explore new harmonic terrain. Some songs just spend the bridge traveling to and back from the subdominant, but other songs seize the chance to migrate somewhere quite new (I’m talking to you, “Land of Confusion”).

The bridge is like the “Development” section in the classical Sonata — having established a clear tonal center through most of the piece, a middle section let the composer stretch their legs a little. Single-progression songs lack the option to travel to new key areas, but they still have many ways to achieve variety. We mentioned earlier the idea of bringing in a guest rapper. With total control over the sounds and arrangement, so much more can be done!

“Cake” fails to rise to any such occasion. The second chorus is simply followed by a brief breakdown, where, for four measures, we return to the guitar and handclaps of the intro. Then the chorus roars back in for the last 53 seconds of the song. Even more stops get pulled out to raise the ecstasy — more vocal interjections, another tune, more synths, more sound effects.

But, for me, at a certain point this all falls flat. Somewhere around the second verse or second chorus, you realize, much like Peggy Lee might say, “Is that all there is… to a pop song?” The arrangement keeps screaming, hey, novelty, excitement! And yet what it’s really doing is dressing up stasis with activity. Nothing’s actually happening. It’s a false promise. You can throw all the hyped-up backing vocals and keyboard lines at the final chorus, but it’s an anticlimax. The listener knows it’s not the big moment the arrangement claims to be; it’s not a grand moment where tension is released in a great celebration — because there’s no tension to release. The air has left the balloon.

In contrast, “West End Girls” had a simpler arrangement — but it also featured a harmonic journey. This is why, for me, I appreciated the song much more after I’d heard it a number of times, separated by years. “Cake by the Ocean” had a more immediate appeal to me, with its amazing chorus, but I soon tired of it. Of course “Cake” is supposed to just be a cute dance song with lustful lyrics, not artwork for the ages… but “West End Girls” was for dance clubs too. And I think it’s aged quite nicely.

Remixing the “Cake”

Since “Cake” is such a well-arranged simple party song with such an appealing pop performance, could this song be improved by a little harmonic variety? Of course! To avoid ruining the song’s sunny simplicity, the change would just need to be something subtle.

So, what would we change? The chorus is already glorious, but the verse and especially the prechorus are quite forgettable. I’d rewrite one of those or tweak it in a way that gave the song some energy. The prechorus would be an especially tempting target.

First, the current prechorus is a mere placeholder, a section that aims to shrink into the shadows so that the chorus can shine extra bright. Second, there are plenty of wonderful songs where the verse and chorus lie strongly in the same tonal area, but the prechorus moves away, letting the song achieve a pleasing resolution when the chorus returns to the main key.

One classic move would be to land on a chord that’s the V of one of the key chords in the chorus, like this:

Or, maybe better still:

But the change could be much more subtle. It could even lie in the chorus. What if the chorus used A major instead of an A minor? This tiny change wouldn’t make the song seem more complex, and it might lead to ideas about how to foreshadow this new harmonic inflection in the new prechorus.

Such a chorus might sound like this:

Even though I’ve taken the first steps, I’m not going to try to rewrite “Cake” here — or, not until the day when I can sing like Joe Jonas and produce like Mattman & Robin. Still, I have tried my hand at rewriting other songs whose sound I admire to lend them the structure and harmonic journey I crave, even though I have made them immeasurably worse because I’m the singer.

If you’re brave, check out the devastation I wrought on “Dark Horse.” If you’re still here after that, heck, here’s the whole album of détourned covers.

So, Where Do We Go From Here?

From this article, you can tell I’m quite fond of harmony — of making things happen with pitches. But there are plenty of other excellent ways to achieve variety. Just look at the world of classical/new music. As many composers abandoned tonality and recognizable tunes in the 20th century, they doubled down on other musical elements.

Since they could no longer achieve variety by introducing a new tune or a new tonal area, they turned to textures, dynamics, the density of notes per area of time, and new sound colors instead. Of course, all of these techniques had also been used previously to delineate sections in tonal, tuneful pieces, but now composers relied on those more than ever.

Unlike classical/new music, pop songs are still built on a foundation of chords and melodies. Even though pop music has spent the digital era exploring the new possibilities of sound, songwriters still have the option to create variety and structure using harmony. They’re just making a choice not to exercise this option. So, my first suggestion would be: if that chorus isn’t popping, or if the song’s energy sags when you return to the verse – consider changing some chords. It’s easy. It’s fun. You can even change keys!

I admit that my ear is too steeped in other kinds of music to truly judge whether multi-progression songs are an option for much of the modern Top 40. While these songs do exist, too many chords might make a song sound uncommercial, perhaps too close to the dreaded musical theater.

In that case, if you’re going to work with a single progression — be creative! For each section, find a melody that explores different relationships between your chords. You can make the same chords sound very, very different. Some examples:

- Katy Perry and Ester Dean’s song “Firework” leverages a single A♭-B♭m-Fm-D♭ chord progression to massive variety in a verse, pre-chorus, chorus, and bridge that all sound quite unlike each other. It’s a master class in how to make a single-progression song sound like a multi-progression song.

- Daft Punk, Nile Rodgers, and Pharrell Williams’ “Get Lucky” has a verse, pre-chorus, and chorus that contrast greatly without changing chords.

- As I write these words, the #1 song on the American Top 40 chart is “Blinding Lights” by The Weeknd. The Weeknd has been known to write multi-progression songs. I happen to be a fan! “Blinding Lights” sticks with one progression, but listen to this song and notice the ways in which Abel Tesfaye finds melodic and even harmonic variety among sections. I think it works great, even though I do sneakily suspect that a global harmonic journey would make me get tired of it more slowly.

Going back to the 1990s, listen to “No Scrubs,” which switches things up in a glorious bridge. Check out the astonishing rhythmic variety in “Say My Name.” And let’s not forget “Smells Like Teen Spirit.”

Do it! Establish contrast! Make your song interesting. If you expect it to get 100,000,000 streams on Spotify, making those 100,000,000 streams a deeper, more meaningful artistic experience is the least you can do. It is… your duty.

Ben Morss earned a BA in Computer Science from Harvard and a PhD in Music at UC Davis, which he immediately squandered by playing with bands like Cake, Wheatus, and Onward Chariots. An alumnus of the BMI Musical Theater Workshop, Ben co-wrote two musicals based on Angelina Ballerina, and he’s currently working on a musical/opera that’s not really about Steve Jobs.

I miss those artists.