In this piece, Daniel Reifsnyder explores how Bob Dylan’s protest song “The Hurricane” helped draw national attention to the plight of wrongly convicted Black activist and former boxer Rubin Carter.

Guest post by Daniel Reifsnyder of Soundfly’s Flypaper

America has been grappling with racism and inequality for hundreds of years — a struggle that has even continued through today to dominate our present reality in numerous ways. Sadly, racism and inequality are likely to continue to plague our communities into the future, but that doesn’t mean we can’t voice our opinions, express our desires for change, and use creativity to build support for movements.

In the 1960s and ’70s, protest songs became an important way to bring attention to injustice and shine a light on the marginalized and oppressed. Today we’re going to talk about one such occurrence and the story behind it.

This article reflects on Bob Dylan’s epic protest song “The Hurricane” — which helped bring about national attention to a wrongly convicted Black activist named Rubin Carter, a former boxer who was serving life in prison for a crime to which no evidence ties him — and what we can learn from this tragedy.

“Here comes the story of the Hurricane…”

Rubin “Hurricane” Carter was a promising athlete born in New Jersey in 1937. He got his nickname as a result of his fast and furious punches, and an uncanny ability to achieve knockouts very quickly. In the 1960s, he went pro as a boxer, which kickstarted an impressive career that led him to become a top contender for the World Middleweight Crown.

That was, at least, until he was falsely accused of murder and convicted by a nearly all-white jury. Here are some highlights from his early career showing his incredible potential.

Being Black in the ’50s was ultimately a crushing existence of poverty, oppression, and daily persecution. Carter’s hometown of Paterson, New Jersey was divided and segregated by color; certain restaurants and establishments simply would not serve the Black community. Schools, busses, and most other institutions were segregated and separated, and the threat of violence was almost always present. During a hunting trip, Carter and his family were nearly run off the road by a white man in a truck.

Local police were no allies to the Black community of northern New Jersey either. People of Color were routinely harassed by law enforcement on the flimsiest of excuses (does this sound familiar?), and were often the first to be targeted as well as the last to be believed.

Unfortunately Carter got himself onto the police radar at an early age for attacking a man with a Boy Scout knife. According to Carter, the man was a pedophile who was preying on his friends and sexually assaulting him. But rather than investigate the alleged pedophile, Carter was quickly sentenced to seven years in juvenile prison at the age of eleven.

Perhaps if he had kept his head down, the young Carter could have eked out a life in this landscape of staggering inequality — but a fighter he was, and so he instead decided to take a stand by getting into activism. Initially, he marched and protested with Martin Luther King. He became an outspoken Muslim and increasingly used his rising star status and media spotlight to bring attention to the cause of racial injustice and equality.

His increasing success as a boxer allowed him to live loud. Carter wore expensive tailored suits and drove a new custom Cadillac with his name emblazoned on it; this level of swagger must’ve been highly unusual for white people to take in at the time, and Carter must’ve had a target painted on his chest. Here was a successful Black man, but someone already branded locally as a “troublemaker” from his years in juvenile detention.

It’s no surprise they were looking for an opportunity to take him down.

“Pistol shots ring out in the barroom night…”

And then, on June 17th, 1966, at 2 AM, two Black men entered a bar in Paterson and killed two white men and a woman, and wounding a third man. Carter, having spent the night club hopping, met his acquaintance John Artis, and was giving him a ride home when they were stopped by police on route.

Carter and Artis did not match the description of the shooters other than that they were both Black. After being hauled in for questioning and passing lie detector tests with flying colors, police trotted both of them in front of the victim who had been wounded. The witness, Willie Marins, insisted these were not the men that attacked the bar.

The woman who was shot, Hazel Tanis, miraculously survived and clung to life for a month before succumbing to her injuries. During that time, she was able to describe to police in detail, the look of the men who stood over her at point blank range and shot her multiple times. When she was presented with photos of Carter and Artis in a lineup, Tanis did not recognize either of them them. In fact, she pointed out two different individuals entirely.

But despite the lie detector tests and eyewitness statements from the victims, police singularly continued to pursue Carter and Artis as primary suspects in the Paterson killings.

“You’ll be doin’ society a favor… that sonofabitch is brave and gettin’ braver…”

Two career criminals, Alfred Bello and Arthur D. Bradley — who were committing a burglary in the neighborhood at the time of the murders, and one of whom was robbing the register of the bar right after the shooting — claimed to have witnessed two Black men exit the bar after the shooting started.

In return for dropping certain charges against them, the duo agreed to implicate Carter and Artis during trial. The state’s case was, unsurprisingly, very weak. Not only did they never find a murder weapon, but police also never bothered to conduct gunpowder tests on either man, which would’ve determined that they had recently fired a handgun.

Normally in a brutal triple homicide, the suspects might have bloodstains and splatter on their clothes; neither Artis nor Carter had any whatsoever. The prosecution claimed they found bullet shell casings in Rubin’s car — a fact that Carter’s attorney challenged. Those shells were not even of the same type used in the murders.

“The DA said he was the one who did the deed… and the all white jury agreed…”

Being a notable figure locally, and having been at multiple clubs that night, Carter was able to provide extensive witness testimony placing him elsewhere at the time of the murders. When he took the stand, he wore the same cream-colored suit he was arrested in the night he was accused. He did this to highlight the fact that witnesses claimed the men who shot up the bar (and did not match either man’s description) wore dark clothes.

Nonetheless, the jury (all white but for one West Indian) convicted both Rubin Carter and John Artis on all counts. The sentence: Life in prison.

It is important to remember that this was 1967, a time of racial upheaval. The 1965 Watts riots were fresh in people’s memory, and the “Long, Hot Summer of 1967” which included 159 race riots across the country was happening at that very moment in time. The fact that here in small city New Jersey, two Black men allegedly killed three white people only underscored the racial tone. The white community of Paterson got its way this time; a troublesome, uppity Black man was put in his place.

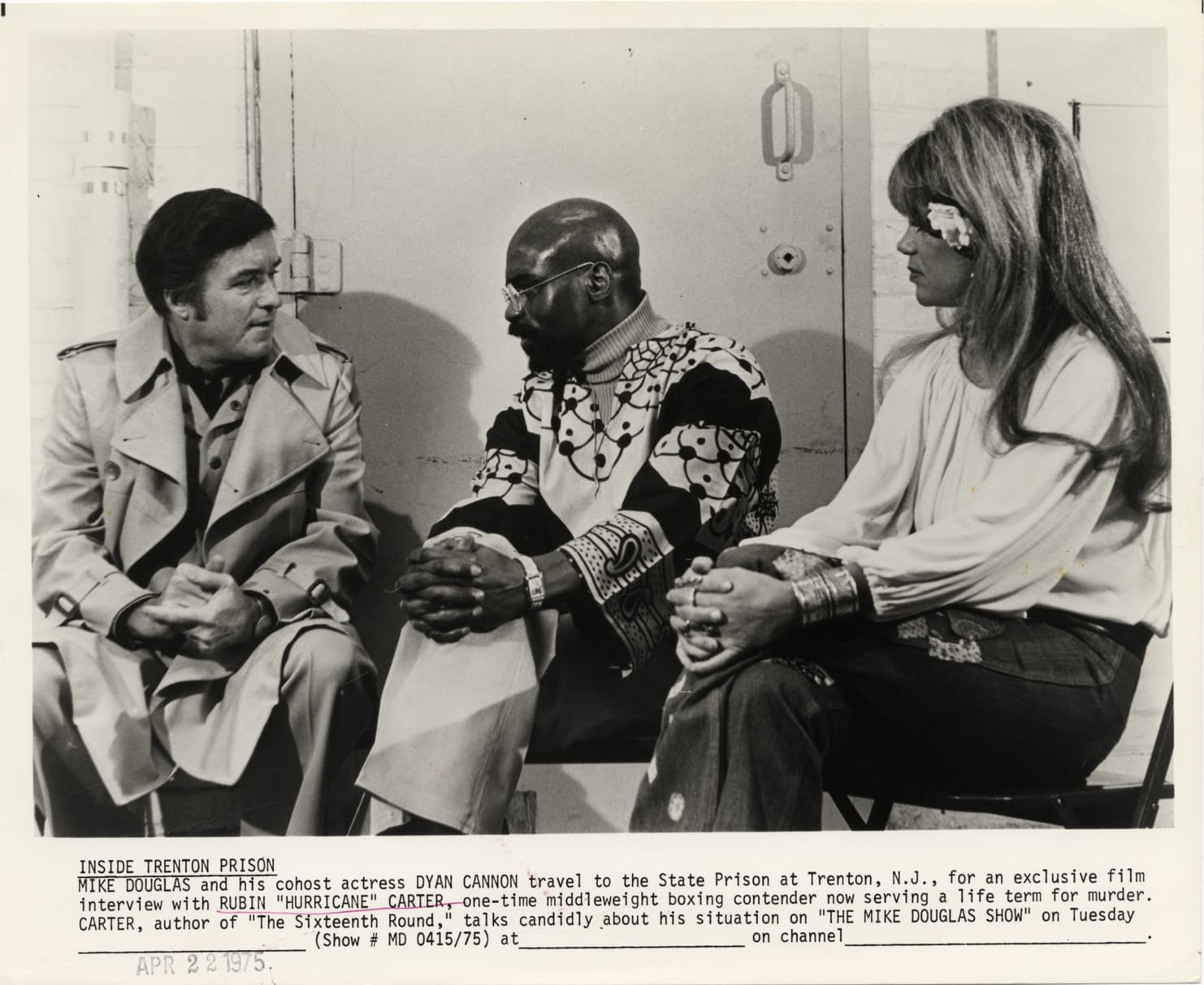

While in prison, thanks in part to his celebrity status, Carter was offered a book deal, the result of which was a 1974 autobiography called The Sixteenth Round. After this book was published, many reporters, celebrities, and dignitaries were interested in his case, including Coretta Scott King, Muhammad Ali, Burt Reynolds, and Stevie Wonder; and contributed to Carter becoming a national conversation topic.

Yet despite the public outcry, celebrity attention, and the state’s obviously weak case against him, Carter and Artis’s appeals were routinely denied. That was until 1974, when the prosecution’s star witnesses — Bello and Bradley — recanted their statements naming Carter and his friend as the murderers. Rubin’s defense team successfully used this as the basis to overturn his conviction and the prosecution decided to try Carter yet again.

Unfortunately, it was all for nought. Bradley refused to cooperate further, and Bello recanted his recantation, reverting back to his original story (with some key variations). And once again, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, Carter and Artis were again convicted; their original life sentences reimposed.

In the midst of all this, Bob Dylan met with Carter after reading his biography, and penned his newest modern day protest song, “The Hurricane.” In 1976, between being sung on tour, spun on the radio, and talked about in the media, the song helped raise even more awareness as well as funds to help Carter’s situation get a closer examination. It’s an incredible song that went all the way to #33 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Dylan stepped into the ring for Carter. But in doing so, he became a lightning rod for controversy himself.

Dylan was immediately accused of factual inaccuracies, including directly misquoting key figures in his song and exaggerating certain details of Carter’s career. Dylan’s label, Columbia, wrung their hands about this as well. Worried they’d be sued for libel, they pleaded with Dylan to change some of the lyrics and re-record the song; and, although he did, he was eventually sued by at least one witness.

Dylan won. Despite any inaccuracies it may have, the song was never intended to be one hundred percent factual.

One more note on Dylan’s song. I would be remiss here if I did not add a note about the fact that Dylan uses an offensive racial epithet in his lyrics. While offensive, and not something I personally would use in my own songwriting, it gets to the actual issue being discussed: Race in America; how we talk about race; how we engage with it; and how race affected the outcome of Carter’s wrongful imprisonment.

While I certainly don’t believe Dylan is racist, looking at this from a purely songwriting angle, it puts listeners in a difficult spot because the word he uses isn’t his to use. It’s a word that immediately triggers trauma in many individuals. And yet he does use it, and he makes us sit with it, shocked and uncomfortable. The goal, as with the rest of the song, is to shock the country to this injustice, both Carter’s and America’s.

One last complicating aspect of Carter’s story that gets little attention amidst the rest of the drama, but I feel is important to mention, is activist Carolyn Kelley’s 1976 accusation that Carter violently assaulted her to the point of blacking out in a hotel room. Though he was never charged for the assault, evidence and accounts do seem to truthfully corroborate Kelley’s retelling of the incident, and it did have a negative effect on Carter’s public appearance at the 1976 retrial when he was again sentenced to life in prison.

But in 1985, nearly twenty years after his original conviction, Carter’s life sentence was finally overturned and he was released from prison (Artis had been paroled just a couple years prior) due to the newly appointed Federal Judge H. Lee Sarokin granting a writ of habeas corpus. Sarokin found the trial to be rife with racial prejudice, “grave constitutional violations,” and found the state had withheld exculpatory evidence.

The U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the judge’s decision to overturn, and with the Supreme Court declining to hear the case, the prosecution had little choice but to drop it. Sarokin never heard the Dylan song, and in fact declined to listen to it when someone presented it to him.

“That’s the story of the Hurricane…”

This is a mysterious story, with strange twists and a lot of uncertainty. The reason we tell the story of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter is not to glorify an imperfect man put up on a pedestal by a cultural icon. We tell this story because of what it reveals in our own justice system, and the imbalances in sentencing and evidence-consideration when it comes to racial bias.

For Carter’s part, he used his newfound freedom in a way you might expect; he became a public speaker and advocate for the wrongly accused. He moved to Canada and became a naturalized citizen — perhaps understandably, no longer feeling comfortable in the U.S. He died of cancer in 2014, a free man.

Daniel Reifsnyder is a Nashville-based, Grammy-nominated songwriter, having started his musical journey at the age of 3. In addition to being an accomplished commercial actor, his voice can be heard on “The Magic School Bus” theme song and in Home Alone 2. Throughout his career, he has had the honor of working with the likes of Michael Jackson and Little Richard among many others. He is a regular contributor to several music related blogs, including his own, Songsmithing.net.