Prison Music: An Historical Primer

In this piece, Amanda Petrusich takes us on journey examining the long-standing relationship between prisons and music, and the power of music (performed both by and for the incarcerated) as an agent of personal transformation.

Guest post by Amanda Petrusich of Soundfly’s Flypaper

In December 1972, Bruce Springsteen – newly signed to Columbia Records, underfed, swaddled in a hooded sweatshirt, still answering to “Brucie” – plugged his guitar into the wonky sound system of the prison chapel at Sing Sing, a maximum security correctional facility in Ossining, New York, about 30 miles up the river from Manhattan. Greg Mitchell, a writer and editor at Crawdaddy, had secured a spot in the crowd — he’d been cajoled into attendance by Springsteen’s then-manager, Mike Appel — and was scribbling notes for what would ultimately become the first sizeable piece of journalism to concern Springsteen, published in Crawdaddy in 1973.

Springsteen was signed to Columbia Records as a folk singer (the first “next Dylan”), but he arrived at Sing Sing with the E-Street Band, and, according to Mitchell, figured the crowd might appreciate a rollicking, 20-minute version of Buddy Miles’ “Them Changes” (“Well, my mind is goin’ through them changes / I feel just like committin’ a crime”). By Mitchell’s account, the entire show was loose, unpredictable. Some of his recollections read, now, as nearly apocryphal.

“In the middle of an R&B song, a short, squat, bald black guy with bunched muscles came rumbling down the aisle like the law was still after him,” Mitchell wrote. “He got past the guard, hit the stage at a gallop, reached into his shirt, and pulled out… an alto sax!”

Jailhouse concerts are considered rehabilitative for the inmates, and bestow a certain kind of outlaw credibility to the performers — a distinction first crystalized when Johnny Cash released At Folsom Prison in 1968, and inadvertently re-inflated his career, now with an added air of “fuck-off” recalcitrance.

Many commercial genres have thrived on the presentation or performance of a certain sort of countercultural insurrection, and booking a gig at a prison quickly became a shortcut for declaring your own sense of disobedience.

Following At Folsom Prison’s success, the Sex Pistols, Big Mama Thornton, the Cramps, and John Lee Hooker each released popular live albums recorded in prisons. Cash himself had performed at several prior to Folsom, and in 1969, he released another album recorded in one, the now triple-platinum At San Quentin. For Springsteen — a protest singer, even then — the booking made sense: Here was defiance, bodied.

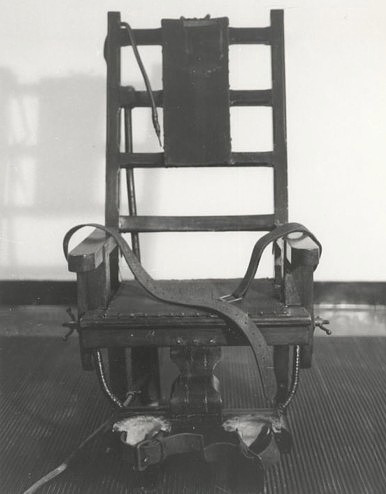

Sing Sing, which opened in 1826, was the site of 614 executions via its electric chair (“Old Sparky,” in the parlance of the time), including the botched (and contentious) killings of convicted traitors Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, and the Italian anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.

+ Read more on Flypaper: Check out our full week of content on music in, about, and from prisons here.

New York State abolished capital punishment in 1965, but Sing Sing still houses around 2,000 inmates, most of whom have been convicted of violent crimes; per a 2009 report, 58% of Sing Sing’s population is serving a sentence of a decade or more.

It feels redundant to call an American prison notorious, most are hotbeds of abuse and mismanagement, but Sing Sing has long been fingered as a particularly gruesome place to pay for wrongdoing. In his 2000 book Newjack, a masterwork of immersion journalism, Ted Conover goes undercover as a corrections officer at Sing Sing for a year; he describes “a feeling of imminent confrontation, of badness just ahead” as suffusing his days.

When I was a kid, growing up just north of the prison, near Croton-on-Hudson, I recall it existing in our collective, adolescent imaginations as a nadir, a worst-case-scenario, so grisly as to be surreal. A Nightmare on Elm Street and Sing Sing: Such were our touchstones for fear.

“For nearly as long as incarceration has been considered a viable method of retribution and reform, music has emerged from the cell blocks — songs born of that experience, forged in fields and yards, a way of defining and expressing the loneliness and deep torment of a life shucked of agency.”

Still, music (as recreation, as reward) has long been present there. In a 1915 story for Musical America, a weekly newspaper founded in 1898 to cover drama, music, and the arts, a reporter named Arthur Farwell overheard some disembodied singing while reclining on a porch overlooking the eastern banks of the Hudson. He listened for a while, but couldn’t quite discern the song’s origins.

“By this time I had become excited,” is how he described the experience in his column. He implored his host to help him locate the source, and together they discovered it was piping out of the warden’s office at Sing Sing, where the chapel choir, then comprised of around a hundred inmates, was rehearsing. Farwell praised the practice as empowering, nutritive:

“Many persons will be still be so far under the domination of ancient and limited ideas as to think it strange and even impossible that to give liberty to a large body of criminals should be the means of creating order,” he wrote. Five years later, in 1920, the paper again reported on the music coming out of Sing Sing’s chapel: “Stirring volume and remarkably fine impromptu harmony… impressive in its deeply felt emotional quality.”

In the subsequent century, Sing Sing also hosted an odd number of professional touring musicians, including the Latin pianist, bandleader and activist Eddie Palmieri, who released a two-volume recording, Live at Sing Sing, in 1972.

A few years before, on Thanksgiving Day, 1969, B.B. King and Joan Baez (with Mimi Farina) played a double bill. It was filmed, and eventually aired on television the following year. “I was told that some of you dudes don’t know anything about blues,” King announced between songs, his face gentle. “That’s what they told me. But I imagine quite a few of you dudes have the blues already.”

For nearly as long as incarceration has been considered a viable method of retribution and reform, music has emerged from the cell blocks — songs born of that experience, forged in fields and yards, a way of defining and expressing the loneliness and deep torment of a life shucked of agency.

“It’s a question that gets asked of art frequently, and earnestly; can we separate good work from a bad life?”

In the 1930s and ’40s, the folklorists John and Alan Lomax recorded hundreds of work songs, blues, hollers and spirituals at southern prisons that more closely resembled slave plantations, including Parchman Farm in Mississippi and Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana. Many of those recordings are more complicated and emotionally wrenching than their commercial counterparts. They are essential to any comprehensive understanding of the south in the first half of the 20th century.

It remains challenging, though, to reconcile the spiritual resonance of those songs with the oft-unforgivable malevolence of their creators. It’s a question that gets asked of art frequently, and earnestly; can we separate good work from a bad life? But it is never less ambiguous or more acute than when lobbed at a convicted murderer.

J.B. Smith, who was recorded by the folklorist Bruce Jackson in 1965 and 1966, at Ramsay State Farm in Rosharon, Texas, sings in a pure and steady voice about regret, contrition, the despair of internment. His performances are exquisite; they awaken something like empathy, if not devastation. Ergo, it feels necessary – ethically crucial, in some complicated, non-instinctive way – to recall, over and over, that Smith ended up at Ramsay because he killed his wife in a fit of ferocious jealousy. That he is not, in fact, singing her back to life.

A half-century later, less music is emerging from prisons, in part because folklorists are no longer shuffling in with microphones. “Neither Alan nor I could now do the work we did then,” Jackson wrote in 2014, in an essay accompanying Parchman Farm: Photographs and Field Recordings, 1947-1959. “The prisons were awful, but they let people like us in. The prisons are more awful now, but people like us don’t get in anymore.”

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Making It in Hell: The Lomax Prison Song Recordings from Parchman Farm, 1933–69”

In the fall of 1977, The Clash recorded “Jail Guitar Doors,” the B-side to “Clash City Rockers” and a blunt, careening homage to the MC5’s Wayne Kramer. A few years prior, Kramer had been busted selling cocaine to undercover agents: “Let me tell you ‘bout Wayne and his deals of cocaine, a little more every day,” Mick Jones shouted. “Holding for a friend till the band do well, then the D.E.A. locked him away.”

Kramer was sentenced to 26 months at the Lexington Narcotics Farm, or Narco, a federal prison-cum-drug rehabilitation center tucked away between the horse farms and bourbon distilleries in the green hills of Lexington, Kentucky. Since opening in 1935, Narco had been generous to musicians, and by the mid-‘50s, the prison had become an incubator for young jazz players and a workshop for pros. Reportedly, Chet Baker, Ray Charles, Tadd Dameron, Dexter Gordon, Elvin Jones, Stan Levey, Jackie McLean, Anita O’Day, Red Rodney and dozens of others logged time at Narco.

“The prisons were awful, but they let people like us in. The prisons are more awful now, but people like us don’t get in anymore.”

In his biography of Miles Davis, John Szwed recounts Davis’ fumbled attempt to admit himself in 1951: “Miles, his father, and his father’s new wife, Josephine, drove down to Lexington, and when they arrived, word spread quickly. Red Rodney, a trumpeter who’d played with Charlie Parker, rushed out to meet him, but Miles had changed his mind and had already left.”

Rabbi Joseph Rosenbloom, a chaplain at Narco, recalled the prison’s house band: “The band had an excellence that would have been difficult to match on the street; it needed to make no compromises.” Players were granted regular access to instruments and to practice rooms, and the farm had a 1,300-seat theater where patient-led jazz combos regularly performed to a full house (there are, regrettably, no recordings of any of the performances).

Perhaps most incredibly, in 1964, a band comprised entirely of Narco patients performed on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. There are no extant master tapes of that performance, either, making audio of Narco musicians one of the great lost American artifacts, like Harry Truman’s sword collection, or the final third of The Magnificent Ambersons.

Music stayed omnipresent at Narco in the 1970s and ‘80s, and during Kramer’s tenure, he regularly played in a band. “We did a little program every Sunday in the auditorium,” Kramer said of his time there.

“We played funk and a little bebop and a lot of blues. There was a great drummer, also from Detroit, named Eric Low. We backed up singers, whatever. There was a black sax player, not an inmate, who would bring his group in there and play with us sometimes. He was a mailman, lived around there. He was real good.”

“Audio of Narco musicians is one of the great lost American artifacts, like Harry Truman’s sword collection or the final third of The Magnificent Ambersons.”

Later, Kramer credited Narco with his own evolution as both a person and a player: “I was fortunate to be incarcerated at a time in America when rehabilitation was a genuine part of corrections and was supported with budgets and staffs who knew from experience that the only way to reduce recidivism was for prisoners to learn new skills and attitudes as tools to help them become contributing members of society. Not only did I grow as a man, and a musician, but music also allowed me to be of service to my fellow prisoners while I was locked up. Our prison band performed regularly for events in the facility and we even played outside the prison in community outreach events that were a benefit to all.”

Since his release, Kramer has become a pioneering advocate for prison music programs. In 2007, Billy Bragg, in an homage to the late Joe Strummer, founded Jail Guitar Doors, a program, named after The Clash’s song, that provides musical instruments — an established rehabilitative aid — to incarcerated convicts in the UK. In 2009, Bragg partnered with Kramer to bring the program to the US. “From our experience, we know that music can give voice to deep complex feelings in a new, non-confrontational way,” they explain in their mission statement.

There are other organizations dedicated to deploying music as a curative and reenergizing force, more useful than punitive approaches (studies reiterate that prisoners enrolled in various forms of art therapy inspire fewer disciplinary reports, and usually have lower rates of recidivism). Researchers have amassed a considerable body of empiric evidence supporting the emotional and physiological benefits of music as therapy.

Even Plato, writing in 380 B.C., understood its muscle: “Musical training is a more potent instrument than any other, because rhythm and harmony find their way into the inward places of the soul, on which they mightily fasten, imparting grace, and making the soul of him who is rightly educated graceful, or of him who is ill-educated ungraceful,” he wrote in The Republic.

“Short of illicit substances, music is the most effective anesthetic to the pain of long or short-term incarceration.” – Erwin James

In 2015, Carnegie Hall’s Musical Connections program helped Sing Sing inmates stage four concerts of Duke Ellington’s music, including one that was broadcast throughout the facility on an internal television channel. Rehabilitation Through the Arts, a program founded at Sing Sing in 1996 and now operating at five prisons in New York State, organizes workshops in theater, dance, movement, visual arts, voice, music and creative writing.

That sort of hopeful, community-based outreach is noteworthy, if still anomalous, within a system that can often feel irreparable.

In “The Sing Sing Follies,” a 2005 story for Esquire, John Richardson followed one of the productions put on at Sing Sing by Rehabilitation Through the Arts, and wondered: “Can art really rehabilitate a man? Does singing and dancing really heal?”

His questions are reasonable. They speak to an ancient idea — that music and art should be considered essential bits of a person’s moral education, imparting things that might otherwise be very difficult to learn. That music can truly change a person, or at least help sublimate and assuage feelings that might otherwise be hard to access.

It is also a way of making certain punishments seem more humane. “Short of illicit substances, music is the most effective anesthetic to the pain of long or short-term incarceration,” the journalist Erwin James (who, in 1982, was convicted of killing two men, and served 20 years of a life sentence at HMP Wakefield, in West Yorkshire, England) suggested in a 2008 piece for The Guardian.

Any case for the presence of music in prison, whether it’s being performed by or for the incarcerated, is, in the end, a case for music as a significant agent of personal transformation, a source of deep comfort. It’s predicated on the possibility that something true and remedial can be communicated through sound — something that might be garbled or reduced via any other path.