Can A Song Ever “Grow On Us” Again In The Age Of Spotify?

The streaming era has reshaped the way consumers listen to music in a number of ways, some more obvious than others. In this piece, Fred Jacobs laments the potential loss of the slow burn appreciation of a song that develops over time.

Guest post by Fred Jacobs of Jacobs Media Strategies

There’s one of those “benchmark” features on Facebook that always captures my attention.

Someone gets “tapped” to spend 10 days, selecting a favorite album each day. The idea is that each of these albums has some sort of significance and meaning – that is, your carefully selected choices should be part of your musical foundation.

It’s interesting to check in with people you know – in some cases, it’s not hard to predict some of the artists and even the albums they select.

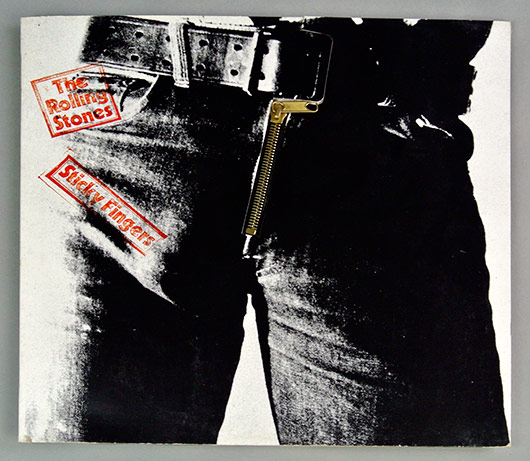

Case in point, my dear friend and WRIF alum, Mark Pasman. He’s wrapping up his “Big 10” vinyl fest. And as a musician – and a very fine one – I’ve been tuned into Mark’s selections during the last week or so. The other night, I was not surprised to see this album pop up as part of Mark’s picks:

When we worked together at WRIF, Mark was the guy championing Elvis Costello from the git-go. He “heard” Elvis before the rest of us did. And while I was slow to come around, eventually Costello (nee Declan MacManus) became one of my fave raves, too.

That’s the way it works. Or worked.

There are some bands, artists, and songs you just “get” the first time you hear them. In Monday’s post, that’s precisely what happened when the young Donna Halper working in an office embedded inside WMMS’ vast music library first discovered Rush’s “Working Man.”

All of us can easily remember that tune we only had to hear once to know, “It’s a hit.”

But what about the other way around? Those songs that had to grow on you, that you had to hear a dozen, or maybe even 100 times, before the brilliance or hookiness of the song finally permeated your brain. Especially those songs on albums where you wondered, “What was the artist thinking?”

For me, it’s not hard to remember some of those tracks I initially hated, that I came to appreciate and ultimately enjoy. In most cases, they didn’t “sound” like the artist, representing a deviation in form or style.

I bought the Rolling Stones album, Sticky Fingers at Harmony House in Detroit in 1971 (the album with an actual zipper on the album cover.) And like we all did, I threw it on the turntable and listened well past the radio hit, “Brown Sugar” (yup, side 1, cut 1). And I remember I ended up liking them all to one degree or another.

Except “Dead Flowers.” It sounded like a twangy Country-Western song. And the very young me couldn’t figure out why the Stones bothered to include it on this signature album. It had to be “filler.”

But like most of us back then, when I put the album on my turntable, I played it – “in its entirety” – as radio DJs used to say. First, that was just the way we were all taught to listen to a record. And second – and perhaps most importantly – it was too much work to walk across the room, pick up the tone arm, skip the “hated” track, and re-place the stylus precisely at the beginning of the next song.

At some point – and I can’t tell you when or how many “spins” it took – but I finally “heard” the song. And to this day, when it comes on the radio or I hear it in a playlist, the window gets rolled down, and I sing the song right along with Mick Jagger.

It’s impossible for me to date myself. And so, when I tell you that people routinely listened to albums – both sides – cover to cover back in the ’60s and ’70s, I know it sounds odd, ancient, and maybe even quaint.

And in so many cases, they came to enjoy some of those tracks that initially didn’t feel or sound right.

They grew on us.

And that got to me wondering whether in 2020, that can ever happen again on any scalable level. The technology used in services like Spotify, Pandora, and others makes it possible and convenient to easily “skip” any time we hear a song we don’t like – especially in the first second or two. We’re not invested. At least when you paid a few bucks to buy an album, you felt like you had to give it a chance. Yes, it was a crude form of getting your R.O.I.

But with playlist services, “song skips” are part of the reason why most people subscribe in the first place. A number of years ago, Spotify data scientist, Paul Lamere, released what became a landmark study with this headline-grabbing finding:

A Quarter of Spotify Songs Are Skipped Within The First Five Seconds

And this was back in 2014. Lamere’s research revealed what we all sensed – our attention spans were eroding, thanks to the convenience and ease of digital technology. It has now become a truism among record labels, artist management, and among musicians themselves that in order to have any chance at a hit (assuming you’re not Adele or Ed Sheeran), that very first song on an “album” better hook in listeners in the first few seconds – or it becomes musical road kill.

It has even spawned “tips” feature article like this one from the Atlanta Institute of Music and Media:

“How to Hook a Listener in the First 30 Seconds of a Song”

Using techniques like “Including a quick melody from your hook in the intro” of a song, AIMM urges musicians to write and record tunes strategically, rather than aesthetically. Practical advice perhaps, but sad nonetheless.

It turns out this “first few seconds” rule applies to news stories, features, and podcasts, too. Tamar Charney, the scholarly Managing Director for Personalization and Curation at NPR One (her title says it all), will tell you that same pattern exists in the way most consumers pick and choose content on her network’s popular app.

Amazingly, Spotify has just created a new feature for its “premium” subscribers – where you can totally eliminate any song you “hate.” It’s a feature The Verge reported on in April allowing you to “hide” songs from every playlist you encounter so you never ever ever EVER have to hear it again. (Unless you run across it on the radio, that is.)

And so, that makes me wonder, whether music will ever “grow on us” again; whether it’s even possible for most young people today to take part in that Facebook exercise of choosing 10 seminal albums in 10 days. (I know what you’re thinking – most young people today aren’t on Facebook anymore.)

And is there any medium where it’s even possible to discover a song, initially dislike it, and eventually have it “grow on you?”

And outside of on the radio, I’m hard-pressed to imagine this scenario happening in this crazy 21st century we’re in the process of enduring. When a radio station “adds” a song and puts it in “rotation,” that’s the moment when you might hear it a dozen or so times, like it or not.

And if by some chance, the song receives airplay on multiple stations in the market, there’s an even better chance you may come to like it – or at least, appreciate it – after so many spins.

That’s because radio is still played in the background, while we’re working or mindlessly driving. It is moments like these when those “dark horse” songs have the chance to actually be heard – and “grow on you.”

It is why to this day, record labels still beg for radio airplay and substantial spins. They know FM radio is the last bastion of “un-skippable” exposure (short of a preset button) where consumers get exposed to music they don’t specifically choose.

And so, at the risk of sounding like I’m from the Cro-Magnon Era, I’m curious about those songs that snuck up on you – that you initially didn’t hear, but that ultimately “grew on you.”

I’ve been told by many people that one of the strange unintended consequences (if you could call it that) of the COVID-19 pandemic is that many of us slowed down a bit, with more time to take in the world around us – our families, gardens, our music, our hobbies.

And even with the “re-opening” happening, and restrictions being lifted, most of us have more time on our hands than we did just a few short months ago.

So, if you have a turntable, grab one of those albums and play it “in its entirety” – side 1 and side 2 – and resist the urge to skip any of the tracks. And maybe in the process, you’ll discover a song (or two) that never received radio play, that rarely make anyone’s playlist, but that an artist wanted you to hear.

You might even add to one of your Spotify playlists.

In writing this post, I started thinking about my own album favorites. And it occurred to me that most aren’t just about the music, but also connect with a point in time in our lives. There’s almost always a story behind these albums.

For me, one of those is “he Nightfly, the first solo album from Donald Fagen of Steely Dan fame. One look at the cover and you’ll see why it grabbed me.

I was programming WRIF when it was released, and we were serviced with both the vinyl and cassette copies of the album. Not long afterwards, station management scheduled a dreaded team off-site in northern Michigan. And for the 4+ hour ride, I grabbed a handful of cassettes, threw them on the passenger seat of my Mazda RX7, and headed “Up North.”

One of those CDs was The Nightfly. And up and back, I probably listened to it at least a half dozen times, all the way through.

The only single from the album that earned any airplay was “I.G.Y. (What A Beautiful World).” Interestingly, the title track – a song about an all-night DJ spinning jazz records, cranking coffee and smoking Chesterfield Kings, taking callers and urging them to “respect the seven second delay we use” never got any substantial airplay. Maybe it wasn’t supposed to.

The song suggested to me the elusive Fagen probably wanted to be a DJ at one point, and in the song, he’s Lester the Nightfly, working at “an independent station, WJAZ,” broadcasting in Baton Rouge from the foot of the fictitious Mt. Belzoni. Yes, it’s more than five minutes long, and it’s side 2 cut 2, never destined to see the light of day.

In fact, Fagen leaves us with this short message at the top of the “lyrics sleeve” of the album:

“Note: The songs on this album represent certain fantasies that might have been entertained by a young man growing up in the remote suburbs of a northeastern city during the late fifties and sixties, i.e., one of my general height, weight, and build.” – D.F.

Pretty personal, right?

Who knows? It might even “grow on you.”

Fred Jacobs founded Jacobs Media in 1983, and quickly became known for the creation of the Classic Rock radio format.

Jacobs Media has consistently walked the walk in the digital space, providing insights and guidance through its well-read national Techsurveys.

In 2008, jacapps was launched – a mobile apps company that has designed and built more than 1,300 apps for both the Apple and Android platforms. In 2013, the DASH Conference was created – a mashup of radio and automotive, designed to foster better understanding of the “connected car” and its impact.

Along with providing the creative and intellectual direction for the company, Fred consults many of Jacobs Media’s commercial and public radio clients, in addition to media brands looking to thrive in the rapidly changing tech environment.

Fred was inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2018.