Music Metadata Showdown: What’s In A Name? Your Cash.

The importance of keeping metadata tidy is essential for artists in the streaming era, but good housekeeping is all for naught if the streamers change song titles and information at will.

It’s an issue which the Mechanical Licensing Collective just brought to the Copyright Office.

Guest post by Chris Castle of Music Technology Policy

There is an unsurprising discussion going on about song titles in the metadata deliberations regarding the regulations mandating the conduct of the Mechanical Licensing Collective quango. The least surprising part of the discussion is that the services change song titles as it suits them.

This explains why you can get your song metadata all nice and pristine and yet your payments are still screwed up because somehow the titles got changed. It’s not a surprise–they’ve been doing it for years. Unless the services are prohibited from continuing this boneheaded..there I said it..practice, their supposed great yearning for the database in the sky will come a cropper.

The MLC recently raised this issue with the Copyright Office:

The DMPs do not have the same method for altering metadata, and their alterations significantly increase the difficulty of matching. There was a discussion of the DLC’s example of changing the sound recording licensor’s metadata for the “Radio Edit” version of the song “Hello,” so that the song title becomes “Hello (Radio Edit).” It was noted that the MLC’s musical works database will have the musical work title “Hello.” Whereas the unaltered sound recording licensor’s 5-character title “Hello” will be a direct match to the MLC’s musical works database title, the 18-character “Hello (Radio Edit)” is much less of a match in the eyes of an automated string comparison algorithm. Similarly, the MLC does not see merit in the DLC’s argument that each DMP should be allowed to alter metadata such as to remove characters that they deem “illegal” (and there is no standard or consensus on what is an illegal character) as this will only hamper matching efforts.

Let’s acknowledge that there’s nothing new here–this problem has been around for years and was allowed to fester into a business practice. I first wrote about it in the context of the “address unknown” debacle where all concerned allowed services to change song titles and then claim they couldn’t find a copyright registration for the title they changed. Sound Kafka-esque? Mais certainement.

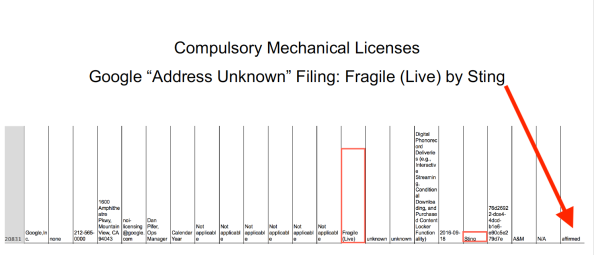

Here’s an example from the address unknown filings that started in 2016. Google filed an address unknown for “Fragile’ by Sting. Bizarre, you say? Yes, of course. But here it is:

Notice that Google affirmed that Google was not to be able to find “Fragile” written by Sting in the public records of the Copyright Office. (Leave aside the absurdity that “Google can’t find [X]”.)

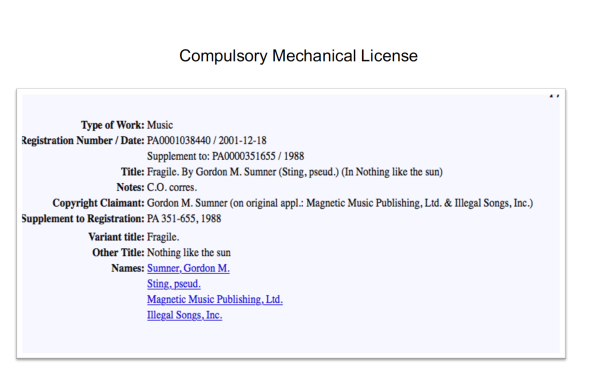

And yet, guess what I found in the public records of the Copyright Office after about a 20 second search:

Dang.

What do you know, “Fragile” written by Sing is in the public records of the Copyright Office. But of course Google only affirmed they couldn’t find “Fragile (Live)” which at best is the title of the recording, not the song. But it’s the song title Google chose to look for, not the actual title of the song–and the compulsory mechanical license available under the address unknown theory is for the song not the sound recording. So wouldn’t you think that the party relying on that compulsory license should have to search for the correct work? Or else…what? Maybe for starters they don’t get to rely on the address unknown because they had the address available to them and chose not to look. And you know what they say–you can’t find what you don’t look for.

Google, Spotify and other services (but not Apple) got away with this loophole of a loophole because they were allowed to. And this isn’t the only one, by the way. There are likely hundreds of thousands of songs that the services claimed they couldn’t find in the Copyright Office records because the service changed the name of the song and then looked for the name they made up. Some might call this fraud (or a violation of 18 USC Sec. 1001, making false statements to a Congressional agency). (I wrote a pretty extensive article on this in 2017 for the ABA Entertainment & Sports Lawyer. I wish it were old news.) So why were the services allowed to get away with this? Don’t let the revolving door hit you on the way out. (And speaking of revolving doors, see Is it Time for the Inspector General to Review the Copyright Office’s Administration of Address Unknown NOIs?)

Now after all the hoorah of the Music Modernization Act Title I (the MLC part) the services are still trying to get away with this hogwash. And who can blame them? They were allowed to get away with it before so why not keep doing the fraud? Of all the predictable insults, this one is probably the most predictable because the services were allowed to get away with it in the millions of “address unknown” songs at a time when serious and sustained opposition might have stopped it. Some things are worth suing over more than others.

Should they keep getting away with it? It will likely just make the black box bigger.

That’s really informative post. I appreciate your skills. Thanks for sharing.