Google, Amazon Leverage Copyright Loophole To Use Songs, Not Pay Songwriters [Chris Castle]

To avoid properly compensating songwriters, big data purveyors Amazon and Google are claiming they are unable to find contact information for the deserving songwriters, instead opting to file copyright notices in what appears to be a music land grab, says Chris Castle.

_____________________________

Guest post by Chris Castle of Music Tech Policy

Two vastly wealthy multinational media companies are exploiting a copyright law loophole to sell the world’s music without paying royalties to the world’s songwriters on millions–millions–of songs. Why? Because Google and Amazon–purveyors of Big Data–claim they “can’t” find contact information for song owners in a Google search. So these two companies are exploiting songs without paying royalties by filing millions of notices with the Copyright Office at a huge cost in filing fees that only megacorporations can afford–an unprecedented land grab in nature, size and scope.

That’s right–Google and Amazon are falling over themselves to use their market power to stiff songwriters yet again. And as I will show, it is not just obscure songs that are affected. New releases, including one example from Sting, are also targets suggesting significant revenue loss to songwriters. (I go into this in more detail on this series of posts.)

I happened to speak to a representative of one of the mass NOI filing companies after a recent panel in Los Angeles who assured me that the reason that his clients were filing these NOIs was not because they did not want to pay royalties but because they were so worried about liability from a “Jeff Price jihad” and that his clients fully intended to pay royalties retroactively once the song owner became known unlike the record companies who are “thieves”. I believe that he believes that his client believes that they’re just trying to avoid being sued for not having the rights, but humor this unbeliever. My bet would be that getting that retroactive payment will take the effort worthy of an act of Congress.

Perhaps literally.

If his new boss clients had a reputation for or history of treating creators fairly, I’d be far more inclined to bet on sunshine and puppy dog tails, but they don’t so I won’t. The problem would be easy to solve–all they would need to do is issue a press release or even a blog post on the Google Public Policy blog stating that it is the official position of the company to pay retroactively. Even if you accept his premise that record companies and music publishers are “thieves,” they never filed millions of NOIs. In the meantime while we’re waiting for that post, I think we have to act as if it is not coming.

The U.S. Compulsory License

Songwriters are the most regulated workers in America. The government sets wage and price controls on most uses of songs and practically everything else about a songwriter’s business–except fulfilling government’s basic role of keeping them safe from piracy and multinational monopolists gaming the system. Congress needs to stop this latest scam.

The latest loophole that Google and Amazon are hacking is uniquely American–the compulsory license for songs. No other country has one. Most songwriters would prefer that the U.S. repeal this legacy anachronism from 1909 that keeps the government’s boot on their throats.

In order to get the government’s license, services only need notify the songwriter (or their publisher) that the service intends to use the song under the compulsory license. Of course, sending this notice of their intention to use the song (called an “NOI”) requires knowing who to send it to, and that is the “hack” that Google and Amazon are exploiting now. Others services surely will follow their market leadership if Congress fails to act.

The hack uses market power to manipulate a loophole in how those NOIs are sent. Common sense tells you that to send a notice, you must know who to send it to, even for a song. But does common sense also tell you that if you don’t know, the law should allow you to exploit the songs without compensation? Particularly if you’re the biggest purveyor of data in human history?

The legacy compulsory license allows services to exploit songs if they decide they can’t find the songwriter–and not pay royalties until the songwriter finds them.

That’s right–Google and Amazon trade on a loophole that allows them to serve NOIs on the U.S. Copyright Office if the song owner cannot be found in the public records of the Copyright Office regardless of what other information is readily available to these services, including their own. And once Google or Amazon serve that “address unknown” NOI, they don’t have to pay royalties and they cannot be sued for copyright infringement–so the millions in filing fees they will spend at the Copyright Office is a kind of insurance premium. This excerpt from the Copyright Act states the rule:

Why Can’t Google Search?

The “address unknown” NOI starts from this premise: Google is supposed to search for the song owner’s contact to send NOIs.

That’s right–Google is supposed to search. Think about that. This 1976 rule was never intended to apply to a music user with Google’s search monopoly. Yet, if Google “can’t” find the song owner after a search, then Google can serve an “address unknown” NOI to the Copyright Office and then exploit the song for free until the songwriter can be “identified” in the Copyright Office records–which may be never.

That registration by songwriters–while prudent–is costly and entirely voluntary. Forcing songwriters to register essentially turns the system into a version of YouTube’s “opt out” debacle, and probably violates international copyright treaties.

But the idea that Google can’t find someone is a remarkable thought. Gmail alone has over one billion users. Google knows everything about everyone and makes billions of dollars from reselling and manipulating that information. Not to mention the fact that Google bought the music licensing service Rightsflow–itself an NOI mill. Not to mention ten years of information Google has scraped from Content ID on YouTube or sheet music on Google Books.

Amazon also has a phenomenal amount of information about music ownership. As one of the biggest CD and DVD retailers, Amazon certainly has a head start in song research.

However–it appears that Google and Amazon are not using their own data for NOIs. Instead, they apparently are buying databases from the Library of Congress that tell them whether a song is registered for copyright or otherwise recorded in the digitized Copyright Office files (which songwriters are not obligated to do in order to get the benefits of the compulsory license). Those Library of Congress databases at best only cover copyrights after 1978 for technical reasons, so tens of thousands of jazz, blues and classical compositions created before 1978 are not included, as well as songs from outside the US before or after 1978.

Why buy this data when these giant corporations already have so much information at their fingertips? Because the point for the services is not to find out who actually owns the songs, the point is to find out if the Copyright Office has a record of who owns the songs based on the Library of Congress data.

That is the hack.

Kafka-esque Moral Hazard

In other words–the government allows Google to claim they can’t find the songwriter even if Google’s own data would reveal their identity just because the song owner isn’t included in the Library of Congress database at the time Google searches. And there’s the “gotcha”.

Kafka’s next book is in there somewhere.

Offering all the world’s music all at once presents a licensing problem that no system will be able to solve due to the sheer numerosity and disaggregation of the creative process. How many songs will be written by the time you finish reading this post and how would you find out who wrote them?

So it should not be surprising that the market has offered a few ways to solve for this problem: Direct licenses (bypassing the NOI altogether) and NOI clearance companies that specialize in maintaining song owner information to send out mass mailings of NOIs (sometimes called “carpet bombing NOIs”).

These are two significant methods available to Google and Amazon and my guess is that these monoliths employ both methods for their interactive streaming services (the kind of service that competes with Apple and Spotify).

What’s the Alternative?

If Google and Amazon cannot find the song owner under their direct licenses or through an NOI company, how can they find the song owner? The easy answer is don’t use the song. But that approach is counter to offering all the world’s music at scale by creating supply that is not responsive to demand.

Deciding which songs are right for “address unknown” NOIs requires some Silicon Valley style hocus pocus. Remember–it’s not that Google can’t find the song owner. The loophole requires that they can’t find the copyright owner in the pubic records of the Copyright Office, even if Google has actual knowledge of their whereabouts.

Then you have to believe that Google knows where to get the information for which direct licenses they want, they know how to carpet bomb NOIs, they have a decade of information in Content ID, but when it comes to some songs, Google has to turn to the Library of Congress? And Google’s only choice is to serve “address unknown” NOIs on the Copyright Office?

Once served, the Copyright Office posts these mass filings on their website in large Excel files so that songwriters can sift through the haystack to find their needles. This hit and miss and self-serving process is fraught with moral hazard and should not be the law in 2016.

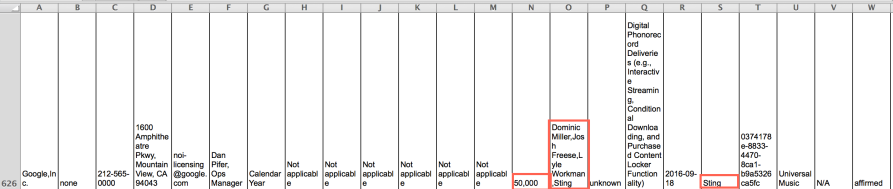

This is what the filing looks like–but realize that “1 NOI” means “1 NOI With An Excel file with over 40,000 songs on it”.

Sting Songs Give Some Examples

A spot check of a couple of Google’s filings reveals that Google is not getting it right. Let’s use three Sting songs for an example.

Sting’s recent release “50,000” (coincidentally a tribute to David Bowie and Prince) is on Google’s “address unknown” NOI list. That song is probably subject to a direct license, but the song copyright registration may not yet have been processed. There’s almost always a delay in processing copyright registrations, so new releases will rarely appear in the Library of Congress database day and date with the song’s release. Google will not be paying royalties on Sting’s song, but will be exploiting it.

That’s right–a song that is a tribute to an artist rights advocate like Prince is itself being ripped off.

Google has also filed an “address unknown” NOI for a song entitled “Fragile (Live)”. My bet is that “Fragile (Live)” is “Fragile”, the well known hit song and anthem of the environmental movement.

This likely means that someone at Google seems to think–or wants to think–that “Fragile (Live)” is a different song than “Fragile”, probably because there is a sound recording registered for “Fragile (Live)” in the sound recording metadata but no song registered by that name in the Library of Congress database. And why would there be if it is the same song? We humans have a way to catch this kind of mistake.

It’s called listening.

This pattern repeats with “Brand New Day (Cornelius Mix)”, also included on Google’s “address unknown” NOI. Again, a version of the sound recording, not the song. The song remains the same.

It is highly likely that the songs “Fragile” and “Brand New Day” were registered with the Copyright Office long ago. That’s probably why the “Live” and remixed versions of the sound recordings show up in Google’s NOI filing for the songs and the original versions do not.

In this case, not only are these songs likely covered under a direct license with Sting’s publisher, but even if they are not, the song owner’s information is identified in the public records of the Copyright Office. The loophole does not apply, but Google takes it anyway and the cost of checking up on a multinational media company falls on the songwriter.

And given that it’s Google, the songwriter will probably have to sue them to a final non-appealable judgment in order to fix the mistake that should never have been allowed to happen in the first place.

The Congress Must Act

The government’s compulsory license has become distorted by rent-seeking behavior by multinational media corporations. It should be stopped or substantially modified. If Google is allowed to use this loophole to profit at the expense of songwriters from its considerable influence peddling and litigiousness, that will be crony capitalism writ large.

Despite the assurances of the mass NOI filing agent, my view is that until I see it in writing, I have to assume that Google and Amazon took this route because it not only offered an opportunity to react to Jeff Price or David Lowery who have the temerity to speak up on behalf of song owners, it had the added bonus of actually stiffing songwriters. The reason I think that is so is because that’s what they chose to do rather than taking the obvious alternative–just not using someone’s property if you decide you can’t find the owner.