The Songwriting Mystique: Who’s Behind A Hit? [Anthony DeCurtis]

As consumers of music, fans often like to think that the lyrics of the songs they hear are as personal to the singer as they are to the listener themselves, but the complicated reality of "hitmaking" is such that this is not always the case, and even when a singer does write their own songs, they don't always do so alone.

______________________________________

By Anthony DeCurtis for the Grammys on Medium

For people who don’t work in the music industry, no activity involved in the creation of music is as cloaked in mystique as songwriting. By mystique I don’t mean mystery, though there’s a strong element of that as well. People believe in the artists they love, and if those artists write their own songs, fans always want to know what inspired them—where the songs came from, if they were based on actual things that happened in the artists’ own lives.

I still remember the tears that came to the eyes of a friend’s wife one day at lunch when I casually explained how many of the great Motown classics were written to order, how Hitsville was based on the automobile assembly lines that had made Detroit famous. She wanted every one of those songs to have been lived, and I felt like a fool for puncturing that lovely fantasy.

We rely on songs to narrate the most important events of our lives — births, marriages, even deaths. And if we’re allowing those songs to reach us in our most vulnerable moments, we want to believe that they meant as much to the people who wrote them as they do to us — that, somehow, they came out of the same experiences. We want to believe that they emerged from the same deep place that we travel to inside ourselves when we hear them.

That’s not always the case, however. Songs are — and, in many ways, have always been — created in as many complicated ways as there are different audiences and different tastes in music. Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff got the idea for Billy Paul’s “Me and Mrs. Jones” when they saw the same couple having lunch everyday at a restaurant near their studio. Were they having an affair? Who knows? But they got a song out of their speculations and Billy Paul got a number-one hit in 1972.

Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff attend the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia 2011 Lifetime Achievement award gala

Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff attend the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia 2011 Lifetime Achievement award gala

The common notion that songs are written by sensitive souls in splendid isolation — garrets, perhaps — derives from the tradition of Romantic poetry, and it’s a fairly recent idea. In contemporary terms, it dates back to the rise of Bob Dylan in the early 60s and the concept of the singer/songwriter. Dylan established a standard that, for artists to be considered credible, they had to sing their own songs.

That Dylan’s voice is, shall we say, so idiosyncratic only helped enshrine that notion. It didn’t matter if you could sing with technical perfection. If you were singing your own words, the cracks in your voice only lent them greater credence. You were singing not because you were some showbiz wannabe, but because you had to, regardless of your limitations, because your lyrics expressed your deepest, truest, most impassioned feelings. No one could deliver your words with as much meaning and conviction as you could, regardless of how scintillating a voice any other singer might possess. You were telling your own story, however rough-hewn, in your own way.

In that regard, Dylan paved the way for the likes of Lou Reed, Neil Young, Leonard Cohen, and many other artists whose voices defied conventional standards of what a singer should sound like. They revolutionized singing and they revolutionized songwriting.

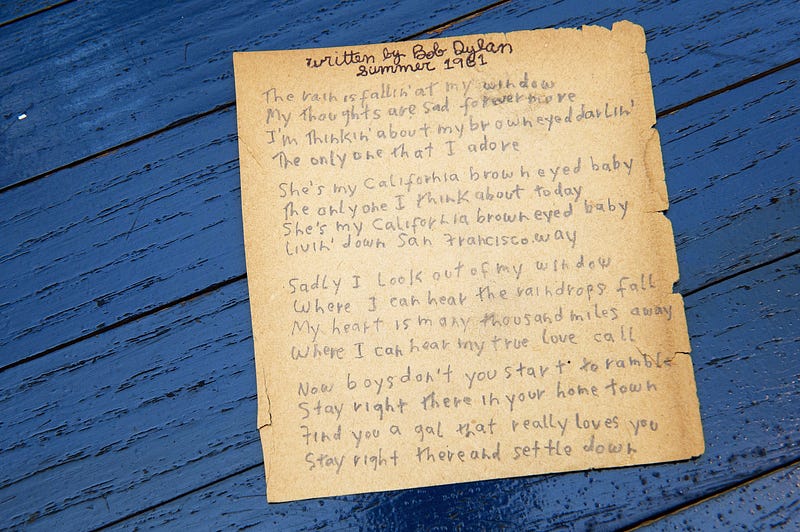

Bob Dylan’s originally handwritten lyrics for ‘California Brown Eyed Baby’

Bob Dylan’s originally handwritten lyrics for ‘California Brown Eyed Baby’

It’s also worth remembering the obvious, but often overlooked point that songs have music as well as lyrics. If a song’s melody or beat isn’t happening, it doesn’t matter how fantastic the lyrics are. People won’t pay attention. Steve Miller, who’s about to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, recently told me that his “secret formula is that a hit single has to have five hooks.” In “The Joker,” for example, there is the harmony singing (“In the car, driving, people love to sing harmony,” he says), as well as “the slide solo, the whistle, the chorus, the ‘midnight toker.’ “

How different is his thinking about a hit he wrote more than forty years ago from the assumption underlying the “writer camps” current today, where representatives of major artists scour the offerings of prominent songwriting teams to see if they can make a match. “It’s not enough to have one hook anymore,” Jay Brown, the president of Roc Nation, told John Seabrook, the author of The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory. “You’ve got to have a hook in the intro, a hook in the pre-chorus, a hook in the chorus, and a hook in the bridge.”

That’s a mighty tall order, something that’s often difficult for any one person to achieve. Which brings us to the kinds of collaborations that are such an important part of songwriting today. Take this year’s GRAMMY nominees for Song Of The Year.

Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space,” a hilarious parody of her man-eating image, couldn’t be more personal in one sense. It’s based on her own experiences as reflected by the funhouse mirror of the media, and she had to deal with both the complexities of the relationships themselves and the weirdness of how they were portrayed in gossip magazines and tabloids. But she didn’t write the song by herself. It was co-written with Max Martin and Shellback, who have also worked with Britney Spears, Carrie Underwood, Usher, and Pink. The music, the words and, to be honest, the compelling video all contribute to what we think of when we hear “Blank Space.”

Taylor Swift performs onstage during the 56th GRAMMY Awards

Taylor Swift performs onstage during the 56th GRAMMY Awards

Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” has become a spontaneous civil rights anthem, but Lamar co-wrote it with Sounwave and Pharrell Williams, one of the most successful hit-makers of our time. It is one of those songs that caught a cultural moment; it provided an uplift that was desperately needed in terrible times. Could those writers have known that? It’s nothing that can be planned — which only makes the song’s galvanizing impact more forceful.

Little Big Town’s smart, moving “Girl Crush” was written by the Love Junkies, the songwriting collective of Lori McKenna, Liz Rose, and Hillary Lindsey. (Nashville, of course, remains a music center where independent songwriters thrive.) It takes a classic country strategy of standing a cliché on its head and coming up with something exciting, fresh, and touchingly emotional.

On “See You Again,” two of the songwriters, Wiz Khalifa and Charlie Puth, combine wildly varied styles — Khalifa’s propulsive hip-hop rhymes and Puth’s delicate ballad singing — to capture the song’s theme of male friendship enduring beyond death. The song’s powerful feelings provide the unifying element.

Finally, Ed Sheeran’s “Thinking Out Loud” is a collaboration between Sheeran and Amy Wadge, a singer/songwriter he’s worked with frequently in the past. Writing together and apart, songwriting collaborators can provide valuable perspective for each other, texture, and insights that either one alone might not be able to muster.

Songwriting aesthetics vary across genres, but as styles of music increasingly merge and audiences have the entire history of popular music at their fingertips, collaborations offer the possibility of new twists and approaches. Two heads — or more — are often better than one. In a recent commercial for IBM Watson, Bob Dylan chats genially with the computer system about his massive, peerless catalogue of songs, which Watson says are primarily about how “time passes and love fades.” When Watson mentions that he has “never known love,” Dylan responds with the openness that has helped keep his music so vital for more than fifty years. “Maybe we should write a song together,” he says. Indeed, why not?