Killing Itself to Live: How the Record Industry Conceived It’s Own Demise

Kyle Bylin, Associate Editor

Throwaway culture, while, perhaps, not limited to commercialized music, appears to stem from highly and quickly popularized songs that are file-shared and listened to for a short period of time. And are, then, later deleted or ‘disposed of’ from the listener’s computer or MP3 player, typically, once the song starts to fade into obscurity or has grown tiresome to the user, due to circumstances such as novelty, over-exposure, or a ‘change of taste.’

As I’ve argued previously, this can be partially attributed to what file-sharing changed about a music fan’s dynamic relationship with the culture that they consume and the numerous paradoxes of choice that are encountered within the realm of the Internet. Most predominately, file-sharing has allowed fans simulate decisions not yet made, or economically ‘committed to’ rather, and has, in turn, caused them to become ever-more passive about their deletion.

Yet, up until this point, what has largely remained a mystery is why things become unpopular and what affect adoption speed has on the abandonment of cultural tastes. Throughout their research of over 100 years of data on first-name adoption trends, Jonah Berger from the University of Pennsylvania and Gaël Le Mens from Stanford University and Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona found that tastes which quickly increase in popularity die out faster.

More interesting still, the researchers also noted that similar outcomes have been observed in the music industry, wherein, artists who shoot to the top of the charts may be perceived negatively and realize overall lower sales in comparison to those who’ve made a more gradual climb. Simply put, people may avoid buying music from an artist that they see as being short-lived, because the attractiveness of the music has decreased and lost its uniqueness.

“This seemingly counterintuitive finding,” they wrote, “has important implications. It suggests that faster adoption is not only linked to faster death but may also hurt overall success.” How these findings relate to the ten years proceeding and following the rise of Napster and file-sharing is where the big picture becomes clearer and new insight is added into what Steve Knopper deemed ‘The Spectacular Crash of the Record Industry in the Digital Age.’

2. Music as a Unit

During the CD Boom, which lasted from 1984-2000, music became increasingly pressured and scrutinized, because executives started to demand that it act like every other unit. This mindset became one of the many catalysts that caused the Record Industry to change from the savvy executives who nurtured talent and developed careers to the corporate types who relied primarily on the infrastructure established through MTV, big-box retail, and commercial radio.

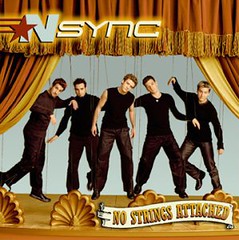

By the late 1990’s, Greg Kot argues in Ripped that the acts dominating the charts were marketing triumphs more than creative ones. And, with these numerous successes, ranging from Britney Spears, ‘N Sync, the Back Street Boys, and Ricky Martin, the major labels began to abandon organic growth, their long-range, career-building view, in favor of the mass-mediated, commercial music, which could provide stronger quarterly growth and profits.

wired generation of fans far more subtle and sophisticated

than anything they could’ve ever imagined."

However, what the hit-factories couldn’t create is loyalty and their practices would go onto cast a divide between themselves and a wired generation of fans far more subtle and sophisticated than anything they could’ve ever imagined. Every time the labels used commercial radio and MTV to spike an artist’s popularity, they had risked, as the researchers noted, realizing lower overall sales, because fans may avoid investing an artist if they perceive them as a fad.

Consequentially, once the teen pop bubble burst in 2001 and the performers that had become the Record Industry’s godsend could no longer sustain their success, the labels began the wake up to the harsh realities that file-sharing seemingly induced. But, no one could forewarn them about the vicious cycle that would be created as a result of their drastic misconceptions and how the very convoluted system they spent years supporting would spiral out of control.

The mass-marketing practices that the Record Industry adopted and mastered in correlation with file-sharing’s rise into predominance may have, in turn, created the ultimate paradox. Wherein the more the major labels focused on producing music that could be highly and quickly popularized, the more expecting fans perceived these artists negatively, perhaps, avoided buying their albums, and preceded to file-share their potentially ‘short-lived’ songs instead.

3.

But, the more the music fans file-shared, the more the major labels were almost forced to produce lowest-common-denominator music, which fed into ever-more vicious cycle. With every new release, every hot new artist that they used their marketing muscle to spike in popularity, it could be said that the Record Industry was killing itself to live. Achieving sustainability and profits the only way these music executives knew how. There simply was no turning back.

The CD-Release Complex, the backbone of the modern Record Industry, built around the idea that fans discover music through the same mediums that major labels use to promote new music, had become so engrained into very fabric of their business, that, without it, they would be lost. Still, they were blind to the fact that the very abstract system they created and used to commercialize culture and bring music to the masses had since become their mental prison.

Previously, artists were established through word of mouth and constant touring, which gradually built a following and allowed an artist develop their creativity and hone their craft. Yet, every year, for the last twenty years, the allotted time table for an artist to be deemed successful shortened and expectations were heightened. With advent of file-sharing and the advances in the Internet, that window of time has considerably shrunk to almost nothing.

On the contrary, digital culture has proved to be as unforgiving as the media landscape that preceded it. Due to the instantaneous nature of the Internet and how it amplifies word of mouth, the growth curve for an artist has compressed from a few years to a few weeks. “Now,” as Jordan Kurland, manger of Death Cab for Cutie and Feist, commented in Ripped, “you run into this phenomenon with people propping things up that shouldn’t be propped up quite so soon.”

“It is a society of instant gratification now, and bands are built up and torn down before they’ve had a chance to create a body of work that represents who they are or what they can do.” In other words, what we’re seeing within every spectrum of the Music Industry, from the top-down corporate media of major labels to bottom-up participatory culture of the Internet: artists that quickly increase in popularity die faster. And, within a climate that supports disposability, the file-sharing community will only continue to thrive and feed on the throwaway culture that is created as a result of it.

excellent article. thankyou

Thank you very much for your comment, glad you liked the essay.

YES! Great essay, I learned something that can help me.

What has really jumped out at the me is the fast cycle for SXSW bands. Hyped heavily before their appearance, buzz bands at SXSW, and then forgotten about six months later. The blogging community seems more guilty of the pump-and-drop than anything I have seen in the past with the music industry. So in terms of hype, I think the current generation of music reviewers/fans is unrivaled.

The emphasis on fast news delivery and trends is getting even more noticeable with Twitter. I haven’t seen a lot of music promotion on Twitter yet (yes, lots of bands are using it, but it hasn’t started to make/break bands yet). But if it comes to pass, maybe we’ll have bands people notice for a few days, and then nothing.

I’ll also add that it’s interesting how we’re seeing the convergence of three trends: (1) trying to build music communities around artists/bands, (2) the use of online tools for marketing/promotion, and (3) the short attention spans of the online community (especially on Twitter).

So the very tools artists/bands are being encouraged to use to create communities are the same ones likely to pull those fans away from communities and on to something new.

you are so wrong… you’ve mistaken the effect of file-sharing for the cause..labels could no longer implement the ‘gradual climb’ artists’ sales because as these bands became popular, the file-stealing robbed them of revenue, they would’ve gained in years past. Then, you make the ridiculous assertion that ” fans perceived these artists negatively, perhaps, avoided buying their albums, and preceded to file-share their potentially ‘short-lived’ songs instead” WHAT??? are you saying that no one would file-steal from these ‘gradual climb’ artists?? are u insane?? and of course, everyone that file-steals will agree with you, because that’s how they rationalize their won stealing (“the record companies DESERVE me stealing their music.”) if you think you could have run a major label profitably during this time, i don’t believe that either….

I dissagree with bandaid22. The more fad artists do gain more sales very quickly due to huge advertising and exposure. The major labels pull all the strings to make it happen, but like in the case of Susan Boyle, people get tired of being force fed something, she didn’t win because everyone was so tired of her. How would you like it if someone fed you fish and chips, three times a day for a month or two months. That is like being force fed the same song on the radio 5/6 times whilst you are listening during the day, people get too tired of it.

I also believe that many people who like fad pop music are not big downloaders of music. Many people do download ‘steady growth’ artists, yes, but many of those people go out and buy more records, especially compared with your one middle of the road album a year 40+ adult. Record labels are so out of touch with consumers, as are bankers and politicians. They like to think they know how to run things, but are being constantly shown to be wrong. Maybe 2009 shall be remembered as the year people actually cared for others instead of their own profit margins, gain and selfishness.

/rant.

Very good article which really sums up a lot of the key factors of why the industry is in the state that it’s in now. I also enjoyed how you presented your ideas objectively, not really siding with the labels or the fans.

The first paragraph of point 3 is especially telling.

“But, the more the music fans file-shared, the more the major labels were almost forced to produce lowest-common-denominator music, which fed into ever-more vicious cycle.”

I think you are right in that people will ultimately download music regardless of how much integrity is involved. Ultimately, all digital media will be free, and in the distant future (hopefully) tangible items will also be free.

The whole digital piracy issue is really a small part of the flawed monetary system which is still in place. As technology/communication advances, more and more products & services will lose value because they will be attainable by anyone and everyone.

Sadly, the govt’/”powers that be” will do everything in their power to prevent this “technological renaissance” if you will.

I just hope people are aware of these circumstances before they occur, as the reality check may not be a subtle one.

“As technology/communication advances, more and more products & services will lose value because they will be attainable by anyone and everyone.”

I agree. But when this happens, we need to have new ways for people to survive: either new ways to earn salaries, ways to trade for what they need, or a system to provide people with at least the basic necessities.

I’m not sure if you envision having everyone return to the days when they grow their own food, make their own clothes, and create their own energy, but if not, we need to have some sort of commerce system.

Excellent article.

From a musical aesthetic point of view , it´s only natural that the music that instantly finds a large audience , does so, by not challenging the listener.

Music that lasts on people´s tastes is one that somehow forces the listener to expand his musical sensibility. It demands focused attention and time for it to grow.

Humbled that I could help teach, thank you for your comment.

Suzanne, I think you make a really good point with your SXSW example. To an extent, in the old model if your first album got reviews of any kind, there was a good chance that your second would receive almost a complimentary follow-up. Now, you may be considered ‘over with’ by the time your second rolls around.

It’s hard to say that, the online community not only thrives, but feeds off of championing new music. Yet, that’s exactly what they do, with 105,575 albums released in ’08 and who knows how many promising singles and EP’s that got picked up, there’s this seemingly endless supply of music, so why settle?

Wow, that is a very well-summed up conclusion. Sometimes, we forget that the same system that allows us to build tribes, has the same power to take them away, as soon as, your no longer considered ‘worth following.’ I’m afraid it comes down to that no marketing plan survives contact with its intended audience.

Furthermore, you have so many people, out to do different things, with the same tools.

Thank you, no seriously, I very much enjoy when people disagree and challenge my ideas. First and foremost, from a more historical perspective of the music industry, labels have been trying to figure out how to create blockbuster albums without the gradual climb, long before file-sharing. Therefore, as I quoted in a previous post: “It was no coincidence, then,” Steve Knopper speculates in Appetite for Self-Destruction, “that Napster, the free file-sharing service, popped up on the Internet at precisely this time.”

Knopper refers to it appearing, seemingly, at the same time, where the Record Industry was the most focused on making instant blockbusters that plumped bottom lines, but couldn’t, say, sustain their overall success, beyond Justin Timberlake, who was able to move beyond the machine that made his career possible. You can’t assert that the record labels could no longer implement ‘gradual climb’ artists because of file-sharing, that trajectory, one could argue, was already in motion during the Post-CD Boom.

That’s the whole point. The very evolution of the Record Industry, from something that took risks and look towards the long term to a more conservative system that thrived on short term gains. And, no, I’m not asserting that people have some kind of moral high-ground that causes them to only file-share certain kinds of music, what I’m arguing, is that beyond the notion of free music. There was also, as Umair Haque noted, back in 2004 mind you, that there was a certain aspect of risk-sharing involved, people trying to mitigate the risks of buying 3 good song albums that the record labels pushed onto the market.

You must obviously realize, ten years ago, things were different than they were now. Kids knew a world with mass-record store chains, whereas today, they probably file-shared their first album long before they had the allowance money to grab up their first album.

Well said. However, “I also believe that many people who like fad pop music are not big downloaders of music.”

Seeing as the artists most popular on file-sharing networks closely relate to those on the Billboard charts, I’d argue that’s not even the case. They are the people most likely, to have no organic connection to music, they just want it and don’t care how.

Thank you very much Ace. While, the objectively, may have simply been a result of my writing style, I’m very glad, that I was able to present my ideas in a way that assumed no favorable side.

Thanks Beni, I think you stated something very telling. Why is Budlight so popular, well, becuase its able to appeal to the most people without challenging or making any of them outsiders. Leinikugel and Guinness, aren’t for everyone, but much like bands like Dream Theater, those who are rabid fans are, but those not part of the tribe, don’t get it.

This is some warmed-over tripe, for sure! The notion that labels lost interest in artist development or that corporate demands edged out entrepreneurial instincts or that instantly popular things engender cynicism are about as old as my grandma’s first spectacles!

My God! Is the record industry (and its self-styled analysts) so completely lost that these self-evident observations actually pass for insight? Ten years down the line (and down the drain), it really is unbelievable to read these same conclusions over and over again without any change in the status quo except increasingly declining revenues.

I remember hearing Queen’s “Sheer Heart Attack” single on the AM radio in my mom’s car back in ’74 (an extremely bad edit, too, by the way) and thinking to myself, “Well, that’s the end of my interest in Queen!”. Wow! I didn’t realize that I was having an extraordinary glimpse into consumer behavior!

Yes, Suzanne, you are right. I don’t want to get off topic too much but there are a few radical minds out there who are currently presenting feasible concepts of how future societies may operate.

The Venus Project is one example…

http://www.thevenusproject.com/

Great article Kyle, and great discussion as well I might add. I too appreciate the impartiality, as I genearlly find that opinions which tend to skew too hard to either side tend to overlook many factors at play. The truth is that the behavior of the labels and consumers alike are bound together to form the end result, which is a broken industry.

I think its true that the labels gave up on long term talent development. This is the result of becoming public corporations, who’s actions are accountable to shareholders above all else. Since company profits are always measured on a quarterly basis, the smart strategy is to maximize your profits in the short term. An artist that takes a long time to grow their fanbase and move records is an expense to a company, but a fast moving overnight sensation is all short term profit. It doesn’t really matter if the act fizzles out fast, you just repeat the process with something else. I don’t think long term future forcasting is in any of their playbooks; perhaps its not because they can’t change their business strategy, its that they won’t…the short term hit may be percieved as too large. The corporate mindset is far different from other business structures…it runs by a different set of rules which are aimed at managing worth…its a delicate balance of profit, expense and image which can seriously derail any sort of extreme initiatives.

Seeing as your Queen “Sheer Heart Attack” example, happens to precede my very existence by roughly fourteen years, I’d argue that I had no intent of brushing off my essay as grand wisdom, unapparent to all, before my grand unveiling. Without sounding too snide, I’d rather like if you could expand upon your criticism with the very original observations and insights that you claim I lack, yet do nothing in terms of objectively adding additional opinions, which could, potentially, better round out this conversation thread.

I’ll have to check it out. Being a “Whole Earth Catalog” boomer, I’ve always been fascinated with this sort of stuff. But putting plan to action is always so hard. Many utopian experiments have faltered for one reason or another. Still, it’s wroth contemplating.

Even if the topic has been covered for the last 50 years, it is still worth revisiting in terms of new online tools. A lot of people think that online communication will improve everything, but in some cases it just speeds up an already bad process.

I’ve been online and an active participant in online discussion groups since 1995. What I see in Twitter is not a revolution, but just an evolution. But what does jump out at me is the almost mob-like way topics rise and fall quickly.

Opps. I meant to say I’ve been online since 1993. The Apple Media Research Lab had an office in Boulder and I spent quite a bit of time there and worked part-time for awhile as a content creator. I was experimenting with driving traffic to OneNet, an early Apple online network. And I was also writing about online marketing. It was very early in that field. I think I may have been the first to create what amounted to an online marketing newsletter/blog.

thanx for the rebuttal, kyle, but you keep quoting things that prove my point, not yours (point being that file-stealing CAUSED ‘throwaway’ music, not that file-stealing is a result of it. *1 u point out that labels had been engaged in promoting gradual climb bands until napster came along –precisely MY point; it was still profitable to invest in gradual climb bands until napster killed the long-term return-on-investment; #2 here’s a quote from your article ” the more the music fans file-shared, the more the major labels were almost forced to produce lowest-common-denominator music’ — exactly my point; it was no longer profitable to promote the gradual climb bands, and u offer no proof that its profitable now. Did we really think that there would be no price to pay for tearing down the industry that as recently as the 90s had successfully marketed Pearl Jam, Metallica, Alice In Chains, and Smashing Pumpkins? Throwaway music instead of acts like these are the price…

So, let’s get this straight. File-sharing did not cause throwaway culture. The technological innovations that led to the creation of the MP3, the introduction of MP3 Players, and file-sharing in general, coupled with complex sociocultural influences and psychological perceptions, gave way to a form of consumer behavior, which involved and allowed people to download music and delete songs from their computers and not care, in any way, whatsoever, about the consequences. In other words, throwaway culture lies in the eyes of the beholder… After all, I said this behavior may not be limited to commercial music. It is, simply where I observed it most predominately happening.

“During the CD Boom, which lasted from 1984-2000, music became increasingly pressured and scrutinized, because executives started to demand that it act like every other unit.”

See above. That’s 1984, music beginning to be treated like a unit. Something you can sell more of from quarter to quarter. Gradual climb artists don’t work like units. Napster 1998. It’s not like they magically abandoned gradual climb artists after Napster. They were already in the process of doing that. Read Appetite for Self-Destruction and get some more historical perspective.

“it was no longer profitable to promote the gradual climb bands, and u offer no proof that its profitable now.”

Again, read a book, this one’s called Ripped. In it, you would find out that the failure rate at labels was 90%. Meaning only 10% of artists signed to labels actually recoup and made money off of the sales of their albums, which, in turn, actually paid for all the ones that failed to catch on. Therefore, you have to realize, it could’ve been any artist that blew up. The point I made was that sometimes, instant successes may realize overall lower sales than those who made a gradual climb. And, the labels, more often than not, seemed to bet on the instant success.

“Did we really think that there would be no price to pay for tearing down the industry that as recently as the 90s had successfully marketed Pearl Jam, Metallica, Alice In Chains, and Smashing Pumpkins? Throwaway music instead of acts like these are the price…”

Maybe at the major label and commercial radio level, but, if you can’t find something you liked in the 100,000 albums that came out last year, then, there’s something wrong with that picture.

Jay, very well-put. Thanks for the comment. Still keeping my eye out for Culture Shocked Part 2.

“The truth is that the behavior of the labels and consumers alike are bound together to form the end result, which is a broken industry.”

Exactly.

thanks Kyle!

Pt 2 is almost done…just needs a few final touches…should be up soon!

It now looks like buying music is a lot about attention span. Twitter is about the thrill of hectic movement, therefore equalling a short attention span. How many tweets can you post during the standardized running time of a single on format radio of approximately 3:00 minutes? The hot new song becomes unattractive more quickly, maybe even before 3:00 minutes are over, when the attention span is shortened by virtual life speeding up.

I guess it’s rather the formats that are long for people to sit through, like films or concerts, that sell music rather than ultra-short ones such as tweets.

Take that with a grain of salt, because I’m not on Twitter and don’t intend to be. But when you believe the whole universe could be shifting in 3 seconds, it just doesn’t make good business sense to buy a song that takes a whole 3 minutes to listen to.

The non-Twitter crowd might actually buy more music in the end because they can enjoy it better.

I disagree that social networks foster a short attention span. As an avid user of Twitter, FriendFeed, Facebook and still MySpace, I’ve established long term friendships/alliances with other users on both a professional and friendship level. Social networks are tools. You get out of them what you put into them. If you toss out short term, low attention span marketing, that’s what you’ll receive from participation in social networks. However, if you’re trying to build a strong(er) brand by establishing long term relationships with fans/clients/associates, you can do so whether you’re a band member or a CPA.

Very interesting thoughts, and there are many truisms stated. But it strikes me as looking for complicated, even mysterious, underlying causes and reasons for both a really simple issue, as well as an extremely complicated series of issues.

(Please excuse the rambling and the length, but I’m on my way out the door.)

Basically, despite what the popular and pro-file sharing community likes to say (over and over and over), you can’t argue with, or compete, with FREE. Free anything will likely trump paying for it, unless it’s toxic.

Aside from that, most of the precepts stated above, overlook the basic issue of SCALE – both the scale of the record business, before and after 1978, and the global scale (and opportunity) of internet file sharing.

Much of the behaviors and reasoning stated above are the result of, or resulted from, and after, those two scales were in place.

Having said that, I would love to sit down – for a couple hours – and get into the details of both our viewpoints. Again, there are a lot of truths in your piece, but it seems to me similar to searching for a ‘problem’ to the ‘solution’ you have reasoned.

It’s both less complicated (start with ‘free’), and more complicated (the nature and history of both the record business and the opportunities afforded by the internet).

(I’ve been saying to friends for years that we’ve gone back to the future. In the earliest days of rock’n’roll, going back to Elvis, Chuck Berry, and up to the Beatles and Dylan, the business was all about selling singles – i.e., the ‘best’ song by the artist – and playing live as much as possible.

Having lived through and evolved during the 60’s, 70’s, 80’s, etc., we’ve grown from a baby business to one that generated so much revenue that it inevitably attracted global conglomerates, who, of course, changed the business to conform with their established business models for their other commodities. With the advent of file sharing, free trumped overpaid rip-offs, and the business crumbled.

Many look at this as technological advancement. I see it as that, but also as a tool that enables people to steal with impunity. As a result, an entire industry has crumbled, and will have to rebuild itself with an entirely different business model. (Can you say look at radio and TV – free to the public, underwritten by commercials.)

So, in a sense we’re back to the 50’s and 60’s. (Even if CD sales are back to the 90’s.)

The music industry has been trying to conceive its own demise for decades. One upmanship is the name of the game in attempting to retain control of a mounting spire built on what? Bad business ethics, poorly written or ill-conceived contracts that delivered less than adequate returns to the artists on even the most popular releases in history.

Then the industry turns on the people who buy the music, suing downloaders using technolgy the recording industry put into practice.

It’s been a litigious model for many, many years. And who knows if we are seeing the best or worst of it at this point in time.

My premise is that music lovers as well as music industry insiders support the professional working class musicians who add value to their craft. Allow them to continue with their careers as they represent a large number of people in this country who are working for a living; supporting families, paying mortgages, making car payments, and putting their kids through college.

What’s be done is done. Let’s look to the future with more support for the professionals, less focus on the hobbiests. If emerging bands find a way to build brand loyalty, they will make it to the professional level, otherwise they’ll have to decide what they want to be when they grow up.

I’d love to think that bands can break based on the new model, but as so many here have pointed out, the buzz is almost instantly forgettable. SM networks are adding a level of ADD to this society in a behavioral sense like none we’ve ever seen.

You say you want a(r)evolution…we all want to change the world.

Janet Hansen

Scout66.com

Excellent, thought-provoking analysis and discussion. Thanks very much, Kyle!