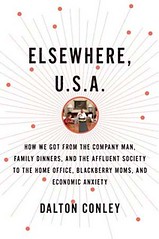

Interview: Dalton Conley of Elsewhere, U.S.A.

Kyle Bylin, Associate Editor

Today I spoke with Dalton Conley, who is University Professor of the Social Sciences and the Chair of the Department of Sociology at New York University and author of Elsewhere, U.S.A.: How We Got from the Company Man, Family Dinners and the Affluent Society to the Home Office, BlackBerry Moms and Economic Anxiety. In this interview, Dalton talks about the “elsewhere phenomenon,” his own industry’s “Napster moment,” and the role of megastars in today’s music industry.

How have the changes in the economy, family, and technology combined to give birth to this new type of American professional?

Dalton Conley: Three forces have come together in a perfect storm of sorts. The first is the most visible and most obvious, perhaps. And that’s the internet / wireless revolution. This has not only allowed up to work all the time when we are not physically present at our employer’s location, it also allows us to stay connected to our non-work lives when we are ostensibly at work. And, of course, this industry itself has accelerated the growth in knowledge sector jobs where we can work anywhere since there is no physical product with which we are dealing.

Dalton Conley: Three forces have come together in a perfect storm of sorts. The first is the most visible and most obvious, perhaps. And that’s the internet / wireless revolution. This has not only allowed up to work all the time when we are not physically present at our employer’s location, it also allows us to stay connected to our non-work lives when we are ostensibly at work. And, of course, this industry itself has accelerated the growth in knowledge sector jobs where we can work anywhere since there is no physical product with which we are dealing.

Second, women—and in particular moms—have entered the labor force in huge numbers over the past couple decades. Back in the 1950s, only 17 percent of mothers with children under 18 worked outside the home. By 1975—the height of second wave feminism—only 1/3 of moms worked outside the home. By 2000, over 2/3rds did. In the most recent economic downturn, men have borne the brunt of job losses such that for the first time, more women are in the labor force than men. That’s an enormous cultural shift. In the meantime, Dad has increased his childcare time by 38 minutes a day. So kids are living increasingly structured lives outside of school and more household tasks—even cooking—have been outsourced to the market place.

Third, every year since 1969 (up through 2007, at least), economic inequality has increased. This rise has taken place almost exclusively in the top half of the income distribution. So the further up the ladder one reaches, the bigger the gaps get. The result is an economic red shift: The feeling that while you may be pulling away from the families just below you, the families just ahead of you are pulling away from you.

The result of these shifts is an increase in work hours at the top such that for the first time, the further up the income ladder you go, the more hours you work. So much for the “leisure class.” Second, for this class of folks, the traditional boundaries between home/office, work/leisure, public/private no longer hold. Social life is increasingly work and vice versa. And the once hallowed boundaries between our home life and the marketplace are dissolving before our eyes.

In ‘The Birth of the Intravidual,’ you argue that the most fundamental line that has been breached is that between the “self” and the “other.”

What aspects of the interpenetration of the social world into our daily consciousness have contributed to our orientation to “elsewhere” and the intravidualism phenomenon?

Dalton Conley: Perhaps the most dramatic erasure of boundaries—and most controversially argued by me—is the boundary between external stimuli and internal selfhood. The constant connectivity of some folks in the Elsewhere Class, I argue, leads to a splintering of the self from a singular “individual” identity to multiple “intravidual” identifies. By being multiple places at once—online, on the phone, where we physically are, on the worry list in our heads—toggling back and forth, we get no time to be “alone” and get to know ourselves. Whereas when I was in college, I could go backpacking through South America and not talk to my family or friends except for a few rushed minutes from a phone cabin once a week or so, today it’s hard to get “lost” and thus have to confront challenges (and confront ourselves) on our own, one of the hallowed traditions of developing rugged American individualism. Second, the increased proportion of our communication that takes place on technologically mediated platforms such as twitter or Facebook means that we are increasingly not communicating one-to-one but broadcasting one-to-many. Among the many consequences of this shift is the elimination of a private backstage, where we let our hair down and only a select few of our intimates see the “real us.” Now our hair is down, so to speak, for the world to see in tagged photos – whether we like it or not. With the erosion of privacy comes the erosion of the private self.

Coming from a nonbiased, sociological perspective, what has it been like watching ‘The Spectacular Crash of the Record Industry in the Digital Age’ and the sociocultural evolution of the music industry as a whole?

Dalton Conley: I can’t say that I am not biased, since I fear that my own industry’s “napster moment” is upon us. With the rise of iTunesU where professors post their lectures, we should be worried—very worried—that parents will no longer pay exorbitant tuitions for some of the same educational material they can get for free. We have to offer something more, something personalized, the way Prince gives away his music in order to promote his concerts. As for my “other” industry, book writing, I am even more fearful about that!

Often times, file-sharing is called out as the main, if not only reason, that the music industry has changed over the last decade.

Are there any other contemporary economic or social conditions that could’ve also played a fundamental role in shaping the bigger picture?

Dalton Conley: I am sure there are. And I am sure I have missed them. Only time will tell, so I leave it to a future sociologist or historian to point out what we, in the midst of all this, have missed… One possibility, however, is the backlash to the Elsewhere Society that we are witnessing in the form of the slow foods, simple living, back to basics movement. Some day, the dominant work-always culture will fuse with its opposite counter culture to form something we can’t even envision yet, just the way that the dominant culture of the 1950s eventually fused with the counter culture of the 1960s.

We’ve seen the convergence of public artist and private individual, as well as, the renegotiation of the fan-artist relationship.

How might we have gotten from the ‘rock megastars’ and ‘MTV celebrities’ of yesteryear to the ‘almost famous’ independent artists of today that seem to make up this middle class of “The Elsewhere Musicians?”

Dalton Conley: Don’t let the YouTube culture fool you: The megastars are still the megastars. The reason that Prince is able to give his music away is that his name is already so big from the “old” distribution model. I don’t think there’s an emerging middle class of musicians quite yet. I think it’s still a winner take all market, even if the rules of success may have changed. I would hope that we would go back to a yesteryear where we produce and consume music locally and thus many more artists would have an opportunity to make a living playing their trade, but I fear that the internet means that we are stuck with viral winner take all markets for the foreseeable future.

Fascinating interview. I particularly like his suggestion of local music consumption being primary, that’s the easiest way to exploit the artist-fan relationship.

Really cool. I liked his example about backpacking through South America. Pretty keen to check out the book now. Thanks!