A Rock Doc Renaissance: Why Now?

With the recent success of films like Amy, Keith Richards: Under The Influence, and 20 Feet From Stardom, it's clear that we're in the midst of a rockumentary renaissance, spurred on by a variety of cultural and economic factors.

_____________________________________

Guest Post by Dan Epstein on Medium

Since the 1967 release of Don’t Look Back, D.A. Pennebaker’s seminal Bob Dylan doc, the music documentary — or rockumentary — has been an integral part of popular culture, giving us a look inside the worlds of our favorite artists.

But while the “rock doc” was once reserved for upper-echelon artists (the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who) or major events (Woodstock), the 21st century has seen a proliferation of documentaries focusing on everything from bands whose influence far outweighed their sales (Sex Pistols, Big Star) to cult heroes (Lemmy, Rodriguez, Harry Nilsson), and even historic recording studios (Muscle Shoals, Sound City).

Amy was one of last year’s most successful music documentaries

The last five years has been an especially fruitful period for rockumentaries. In 2015 alone, we saw new docs on Amy Winehouse (Amy), Kurt Cobain (Montage of Heck and Soaked in Bleach), Keith Richards (Keith Richards: Under The Influence), Bruce Springsteen (The Ties That Bind), Nina Simone (What Happened, Miss Simone?), punk heroes the Damned (Don’t You Wish That We Were Dead), jazz legend Jaco Pastorious (Jaco: The Film), and countless others.

Music documentaries have officially solidified themselves as part of the cinema lexicon.

To what can we attribute the recent explosion of music docs? There appear to be several factors involved, from greater distribution channels thanks to cable and alternative media streaming services (HBO Go, Showtime Anytime, Netflix) to more inexpensive ways to make the films. Also, thanks to music streaming services such as Spotify and Pandora, younger generations have decades of music that’s now easily accessible to them.

Ethan Rudin, CFO of Rhapsody International, sees younger fans checking out classic artists. “These are the most studied music fans, many of them now with their own kids and they use our service as a teaching tool,” Rudin says. “The availability of iconic bands not previously available on streaming services, like [the streaming release of the Beatles’ full catalogue], is also inspiring a new generation of young fans.”

Perhaps it’s this increased access to music that’s led to a greater interest in legacy recordings and sonic roots — things typically explored and placed in personal or sociological contexts in music documentaries.

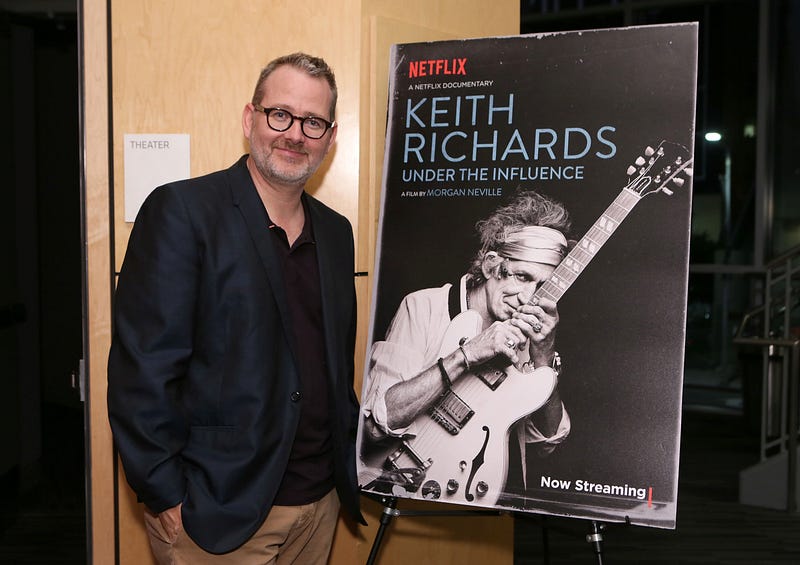

Morgan Neville attends the event “Reel To Reel: Keith Richards: Under The Influence” at The GRAMMY Museum

Morgan Neville attends the event “Reel To Reel: Keith Richards: Under The Influence” at The GRAMMY Museum

“It’s easier to get funding for music documentaries, because it’s obvious that there’s going to be an audience on the other end,” adds Morgan Neville, director of 2013’s GRAMMY-winning 20 Feet From Stardom, and 2015’s Keith Richards: Under The Influence.

The rise of crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and GoFundMe don’t hurt either, eliminating the “down payment” hurdle that’s historically gotten in the way of creative projects, especially those that do not cater to a mainstream audience.

“As a documentarian, you may not get the budget to make the sort of thing you want to make,” explains Rachel Lichtman, who launched an Indiegogo campaign with her co-producer Andrew Sandoval to help fund The Guys Who Wrote ’Em. “I think [crowdsourcing] has been incredibly important in bridging the gap of disinterest from large film companies.”

Also changing the game is the increasingly affordable creation and production process, thanks to digital technology. Searching For Sugar Man, Malik Bendjelloul’s Academy Award-winning 2012 documentary about Rodriguez, was partially shot with an iPhone, using a retro video app.

Between the desire for content from fans and the available avenues to share these films, the number of music docs is indeed on the rise as a result. Showtime confirms that their number of music documentaries this decade have increased 22 percent.

Beyond the growth of alternative media and distribution channels — or, perhaps, because of it — Neville believes that the quality of documentaries has risen, making them more appealing to audiences, a fact backed by the critical and commercial success of films like Amy and What Happened, Miss Simone?(both of which are Oscar-nominated). “I think, in general, that documentaries have lost their stigma; they’re no longer ‘eating your vegetables’ — now they’re seen as movies, which are really entertaining.”

More than simply entertain audiences, today’s music documentaries do double-duty, serving as promotional vehicles for artists. “What I think has really accelerated the surge in documentary making is that the artists and the labels have come to see documentaries as real legacy pieces,” says Neville.

Shirley Halperin, News Director for Billboard, concurs. “The Nina Simone documentary definitely impacted her catalogue and legacy because a lot of people didn’t know a lot about her life. It led to a book by Alan Light, who told me it was directly triggered by the documentary,” she says.

And, thanks to the access that fans now have to explore the world’s music catalogue through online streaming services, that initial exposure to a new (or legacy) artist — whether it’s through a music documentary or a concert your parents dragged you to — can easily result in further discovery and consumption of that artist’s work.

“This is the first generation in the history of pop culture that is actually turning backward,” says Jeff Jampol of Jampol Artist Management, who co-produced recent documentaries on his clients Janis Joplin (Amy J. Berg’s 2015 docJanis: Little Girl Blue) and the Doors (Tom DiCillo’s 2009 film The Doors: When You’re Strange). “Usually what happens is, when we come of age, we eschew our parents’ music and taste in everything, and say, ‘Your stuff sucks — this isour stuff!’ And I think modern generations still do that, but then, all of a sudden, they start to turn backward. They go, ‘What is this? What’s it all about?’ Then they look through the music and find that Led Zeppelin — or the Rolling Stones, or the Beatles, or the Doors, or the Ramones, or Janis Joplin — have something to say.”

According to Jampol, this is a prevalent trend. “The Doors were only together 54 months and they are earning more over the last ten years than they did when they were in their prime.”

Despite that eyebrow-raising stat, the question remains: does the documentary help raise awareness about the artist or is the documentary successful because the fans already know the music? Maybe it’s both.

“The documentary can work for both an existing fan base and new fans,” Jampol says. “Fans of artists always want to dig deeper and stir up some of those memories. If there is an interesting point of view, it can also connect with new fans.”

A snapshot from the documentary 20 Feet From Stardom. Credit: Tremolo Productions

A snapshot from the documentary 20 Feet From Stardom. Credit: Tremolo Productions

“Music films do allow you to bring in other audiences,” says Neville, whose 20 Feet From Stardom significantly boosted the profile of Darlene Love, Merry Clayton, Lisa Fischer, and other artists who were best known as backup singers within the music industry. “The women in 20 Feet have all had incredible, much-deserved opportunities come their way since the film’s release. The impact of a successful documentary worked there, and it worked with Anvil, it worked with Rodriguez, it’s worked with so many others. It’s an incredible marketing tool, and I think everyone has woken up to that.”

Halperin agrees that is definitely the case. The music industry magazine recently broke the news that Universal Music hired someone for film and television development to mine Universal’s deep catalogue for potential documentary subjects, be it, as she says, Kingston Trio or the Beach Boys. “They do because it keeps the money recycling, they get their sync money, they get potential catalogue sales.” For artists, the documentaries make a lot of sense. They are also great for filmmakers and fans for what boils down to a very simple reason: “They make great stories,” she says.