How To Curate (In) The Culture Wars

Ed McKeon discusses the blurring of lines between politics and culture, and why the music industry is far from exempt from the important changes and upheavals currently taking places as a result of the culture wars.

Guest post by Ed McKeon of Soundfly’s Flypaper

Identity is back, big time. But did it ever go away?

From #BlackLivesMatter and anti-Imperialism to #MeToo, gender and sexual equality to expanded identity politics, issues of representation are in the foreground of not only the political sphere but the cultural world too. More significantly, the distinction between the political and the cultural has itself become blurry. The foundations of public monuments, flags and statues, the business interests of arts institutions’ board members, or their sponsorship deals, have all been challenged; and at times, uprooted.

Nor is music exempt. If Mount Rushmore makes white colonial power sacred, especially looking out over Native American land, what about “The Star-Spangled Banner” with its lyrics written by slave owner and anti-abolitionist Francis Scott Key?

As a Brit myself, I know that “God Save the Queen” and “Rule, Britannia!” are equally problematic. Perhaps one of the first acts of would-be President Kanye West will be to write a new American anthem?

The overlap of politics and culture speaks loud and clear when a rapper and fashion icon aims to replace a reality TV show branding mogul as the world’s most powerful man. Culture writer Sara Cascone suggests that West’s mid-term closeness to Donald Trump is reminiscent of a performance art piece by Joseph Beuys in which Beuys spent three days locked in a cage with a coyote, a symbol of the wild American spirit.

The political battles of how we want to live and what we want to become are increasingly fought on the cultural terrain of who the “we” is, and how “we” might understand our place in the world. For those compelled to ask this question, those who don’t see themselves recognized in the rhetorical “we,” it’s clear that for elites some people are more American, more righteous, more civilized, more deserving, more…”human” than others.

What’s also clear is that the old arguments used to claim these privileges are no longer, nor ever were, truly sustainable. Genetic inheritance is undermined both by millennia of miscegenation (there are no “pure bloods”) and by contemporary biogenetics which demonstrates the genetic incorporation of cultural traits. In other words, the ways that we think (and sing, and listen), can and do affect our biology.

Likewise, if there is a one true God, the idea that s/he picks sides or has one brand is untenable when each of the major faiths is fractured, when Christianity alone has over 300 ecclesiastical traditions comprising 33,000 distinct denominations worldwide. Our current moment is one in which the old “certainties” are crumbling rapidly and becoming unrecognizable.

The defining qualities of art, including music, have also been contested. It’s no longer clear what art is.

Yet this crisis isn’t new. It really took hold fifty years ago, in particular as many artists took up the challenges of the “historic” avant-gardes of the 1910s and 1920s — the Futurists, Dadaists, Constructivists, and Surrealists. It’s no coincidence that the modern profession of “curator” emerged in the 1960s.

When the difference between what was art and what was not could no longer just be seen — or seen justly — an advocate was required who could ground an artist’s latest work in context (giving it a so-called provenance), provide a theoretical account of its value, and persuade large numbers of the public to make their own judgements. In the process, the value of contemporary works sold at auction boomed, the audience for the latest art expanded, cities across the world began building new galleries and the number of biennials rocketed.

With its hundreds of traditions and thousands of interpretive denominations, art became vulnerable to its own “success.”

It’s no accident, then, that just as questions of identity and value have returned with a vengeance, so the notion of curating has taken hold beyond the framework of art and museums. Our 24/7 news is “curated,” fashion is “curated,” restaurant menus are “curated,” and music is of course “curated” (even if it’s being done by an algorithm).

What’s less clear is whether curation — as the process of producing value by making difference visible — offers solutions to the problem, or whether it might itself be part of the problem. The Culture Wars can, in fact, be understood as a symptom of this curatorial model.

Consider HG Wells’ The Time Machine (1895), which popularized the idea of time travel as a science fiction genre. Emerging dizzied from his journey into the distant future, the Time Traveller meets two versions of human evolution. The Eloi appear to have created Utopia. This Eden has no war, disease, or hunger, but as a result, its people have become weak, satiated, and simple-minded. These innocents are then prey for the Morlocks, sinister creatures who live underground, hidden. At first, the Traveller assumes the Eloi are the product of a socialist paradise as there are no property or divisions of land among them, whilst the evil Morlock must surely be what became of the capitalists. Only later does he reverse his speculation: Capital “won” at the cost of making its workers sub-human.

Wells studied at the Royal College of Science, London, neighbouring the South Kensington Museum, comprising today’s Science Museum, Natural History Museum, and Victoria & Albert Museum. This sets the scene for the climax of the Time Traveller’s adventure, their now abandoned collections of ancient objects providing an improvised weapon and combustible material for a torch that allow him to escape the Morlocks and journey on.

What becomes evident is that “time travel” was not simply an inspired flight of imagination. The public museum (not just the one in London) was itself a time machine, a technology allowing people to quite literally “walk back in time,” and by implication, to project themselves into the future.

Museums and galleries took off in the nineteenth century as popular attractions, in particular for their ability to present narratives of progress. Arranged in chronological displays, it became possible to move through the products of different civilizations, especially as Imperialist adventures brought back treasures from the cultures they subjugated — what today is increasingly understood as loot and plunder.

Here’s a scene from 2018’s Black Panther that covers this topic from a fictional standpoint. (We broke down the compositional techniques and leitmotif appearances in the film in this blog post).

The history of art could likewise be presented as a series of periods and styles, each succeeding the last until reaching the most modern (or “advanced”) work in the collection. The curator’s role, along with that of art historian and critic, was to classify each item, to place it in its specific history and to assign it a value.

It’s always been much easier to curate the work of the dead, who can’t answer back. Living artists could disagree or resent having the meaning or significance of their work determined by another, especially when comparisons with “Old Masters” were rarely in their favour. It’s no surprise, then, that museums specializing in modern work only emerged from the 1910s and 1920s on (New York’s MoMA was founded in 1929), alongside avant-garde artists who rejected the model of history from which their work had been excluded or marginalized.

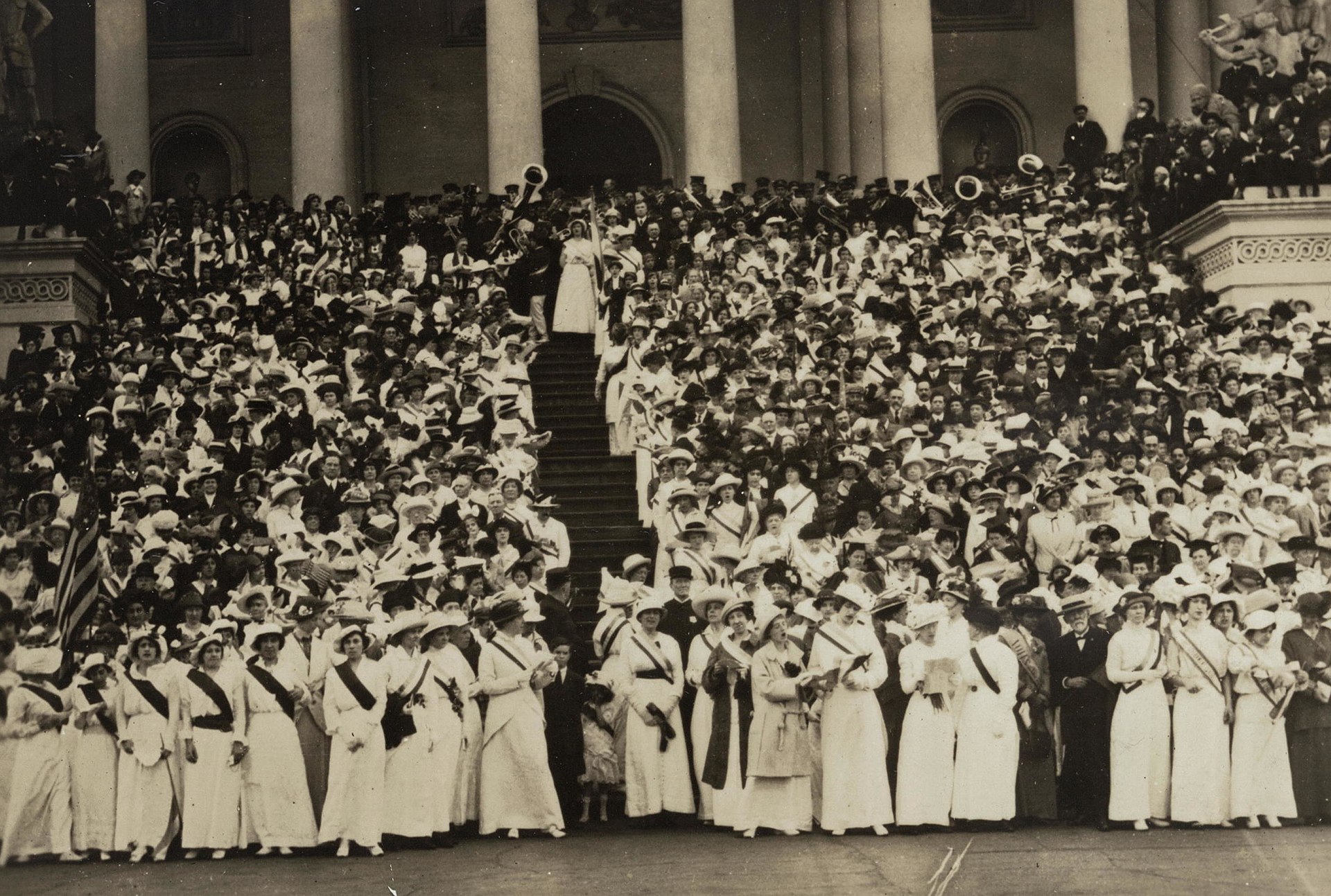

F.T. Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto (1909) famously called for museums to be destroyed. Militant suffragettes in Britain took up the call in attacking the politics of culture by smashing the windows of London’s Sackville Gallery in 1912.

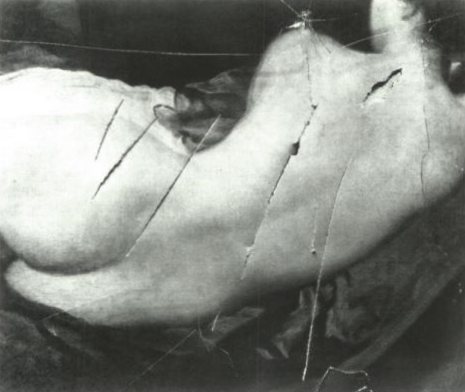

The artist Mary Richardson, under her pseudonym Polly Dick, went further. In March of 1914, she entered the National Gallery in London, and took an axe to Velásquez’ Rokeby Venus as revenge for the state’s destruction of “the most beautiful character in modern history,” Emmeline Pankhurst, forcing the closure of the museum as well as others for a time.

The cause of recognizing women as the equals of men was not only destructive, however. We should also recall the suffragettes’ anthem, “The March of the Women” by Ethel Smyth, as a call for unity and action.

Curators themselves came into the firing line when the politics of art erupted in the 1960s. “Cancel culture” was pioneered by elites who preferred not to have their own dirty laundry aired in public.

Edward Fry lost his job at the Guggenheim when his show of Hans Haacke was cancelled after it was due to include a forensic critique of the business of New York slum landlord Harry Shapolsky. MoMA director John Hightower was sacked shortly after allowing works critiquing the Rockefellers for their support of the Vietnam War — Nelson, as Governor of New York and Nixon’s later Vice President, and implicitly his brother David, the then-Chairman of MoMA — in the exhibition, Information.

The conservative backlash of the “moral majority” was unleashed in the 1980s, giving us the Culture Wars as we now know them. Robert Mapplethorpe was targeted for his Black male nudes, whilst Andres Serrano was made the devil incarnate for his Immersion (Piss Christ), played out against the AIDS pandemic. Art could no longer be separated from its own politics, and curating was recognized as the mechanism by which this was enacted.

Artist collectives like Colab and Group Material took curating into their own hands, pioneering projects dealing with squatting and rent strikes, homelessness, AIDS, and even “democracy” itself.

Such critical curating became exemplary for the first curatorial study programmes in higher education, but the subsequent “institutionalization of critique” — curators emulating critical artists, and acquiring political works for museum collections — led to its own crisis. If nothing changed, if repressive structures remained intact, were “critical” curators not simply complicit in inoculating political art by treating it primarily as art, and only secondarily as political?

Today, curating is increasingly learning from music (much to the disgust of some critics); and vice versa. We are rightly aware of the biases in representation, of genres from which women have been absented, of the privileges accorded to white, straight, and male genres and artists.

The lesson goes broader. Music has struggled more than the gallery arts to keep its separation from politics. It is not only embedded in the music industries, its hit factories, its economies and marketing machinery — something that composer Johannes Kreidler has parodied mercilessly.

Music consistently plays a crucial role in how we form our identities. For many, it makes us “feel like who we really are.” What we listen to is often taken as a sign of our authentic self, which is why politicians have been careful to position their musical tastes accordingly. Music businesses have led the way in manufacturing identities, something in which music curators have been implicated during the era of digital streaming.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Who’s Never Heard of Hal Willner?”

It is the unreliability of a politics of identity that music offers to today’s curating practices. On the one hand, like Ethel Smyth, music can be used to construct bonds of solidarity that can be a resource for groups needing their unity as a foundation for political strength. That can be played in multiple directions, though, not always for the weak against the strong. Racists and fascists sing songs too, even if not very good ones.

Try changing (or “covering”) the national anthem and see what response you’ll get… One of music’s key lessons is that identity is not a given, unless it’s given to, or rather imposed on, you; it’s something we grow into. We perform it each day as a “habit of self” (and one of the very definitions of “performativity”), which is why our tastes and our sense of self can change over time — even if most people establish their musical identity by their late teenage years.

In recent decades, though, tastes like identities have become multiplicative. Fewer people insist on listening to just one type of music, just as our family, friend, and professional networks shape our multiple identities. Music becomes a tool through which we can try out different ways of being ourselves.

Musical politics, then, is not only or even primarily dependent on representation. It is something we enact with each performance, with each listening — in what we listen to, where we listen to it, with whom, and especially how we listen. We have much to learn from musicians such as Pauline Oliveros, whose practices of Deep Listening emerged through the women’s group she established for listening meditations in the early 1970s in response to the political violence of the time.

Are the identities we adopt through music accidental, innocent plays of fantasy and wish fulfilment? Are we comfortable in rejecting, devaluing or delegitimizing some music for the people it is thought to represent. If “music says ‘we,’” as the philosopher Theodor Adorno claimed, who does this “we” include or exclude, and how?

A key musical lesson for curating is this: What politics are we performing when “we” gather together to make meaning, to dance, to party, and to listen?

Ed McKeon is a producer, researcher, and writer who works with musicians and artists at the points where music indisciplines others, whether theatre, installation, object, or performance. He has collaborated with artists such as Pauline Oliveros, Heiner Goebbels, Elliott Sharp, Jennifer Walshe, Matthew Herbert, and Brian Eno. He has presented BBC Radio 3’s flagship new music programme; was artistic director of the British Composer Awards; and remains a Trustee of the Hinrichsen Foundation, on the Editorial Committee of Riffs, and Vice Chair of the British section of the International Society for Contemporary Music. Ed leads an MA programme at Goldsmiths College, University of London on Music Management. His doctoral research at Birmingham City University on musicality and the curatorial is supported through the Midlands4Cities Doctoral Training Partnership, funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council.