What Is The Value Of Exposure When Exposure Is All There Is?

Revenue related to live performances accounts for 65% – 80% of most artist’s income. With that income gone for the foreseeable future, artists are examining all of their other income streams, including streaming.

By Mark Mulligan of MIDiA and the Music Industry blog

There is an existential debate going on at the moment, around whether streaming is paying artists enough. It may feel like a rerun of old debates but it is catalysed by COVID-19 decimating artist income. These are some of the key narratives: here, here and here.

In this piece I lay out the underlying economics of the argument. I also focus wholly on artist income as songwriter income is another topic entirely.

COVID-19 has reset the debate

The latest streaming royalty debate is not an isolated event. It is happening because COVID-19 has decimated live income, leaving many artists worrying about how to make ends meet. Last week, just before this whole debate kicked into gear I wrote:

“Live’s lockdown lag may have the knock-on effect of making artists take a more critical view of their streaming income. When live dominated their income mix, streaming’s context was a meaningful revenue stream that built audiences to drive other forms of income. It was effectively marketing artists got paid for. Now that artists are becoming more dependent on streaming income, the old concerns about whether they are getting paid enough will likely come back to the fore. It is in the interests of both labels and streaming services, that labels use this as an opportunity to revisit their streaming splits with artists. Labels cannot afford to have artists united against the labels’ primary income stream.”

None of this makes the debate any less important, but it explains why it is happening now, and with live revenue potentially set to take years to fully recover, it is a reality that streaming services and labels need to adjust to. It is in the interests of both labels and streaming services that artists feel like they are being treated fairly. But it is crucial that this debate is grounded in a firm understanding of streaming economics and that we do not return to the mudslinging of more than half a decade ago. A debate which, by the way, did not result in any fundamental change to how artist royalties are paid and was eventually followed by labels negotiating smaller revenue shares with Spotify and others.

Where streaming has got us to

Firstly, let’s lay some ground markers:

- Streaming has driven half a decade of recorded music revenue growth, with the market now 42% bigger than it was in 2014

- The wider streaming economy has globalised fandom and engagement

- More people are listening to more music now than before

Streaming has been the change agent that turned around 15 years of decline. But it also completely reframed artist income from recorded music. In the old sales model artists would get a large sum of money in a relatively short period of time. Streaming income is more like an annuity, a longer-term return where the music keeps paying long after release. In the old model artists had smaller but high-spending audiences. With streaming they have larger but lower-value audiences.

For example, a recouped independent artist might expect to earn $4,500 for selling 1,500 copies of an album. That is roughly how much an artist would get from 5,000 people streaming the album 20 times each. The average revenue per user (ARPU) has gone from $3.00 to $0.90 for streaming. The artist has traded ARPU for reach.

This model worked fine when live and merch were booming because more than three times as many monetised fans meant three times more opportunity for selling tickets and t-shirts. This of course is the ‘exposure’ argument streaming services are fond of, which works until it does not. Now that live and merch have collapsed, as the trope goes ‘exposure does not pay the rent’. The previously interconnected, interdependent model has become decoupled.

Put simply, artist streaming economics do not work without live.

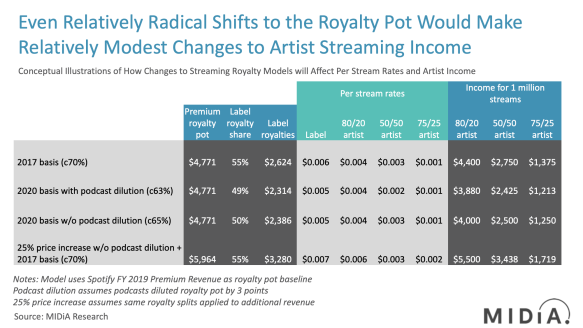

The question is: what levers can actually be pulled and what effect can they have? In the above chart I have used Spotify’s 2019 premium revenues to illustrate how changes in royalty shares can impact what artists earn. I have used a total per stream rate of $0.06 as the base case, which could look on the high side for some artists, but the purpose is to show the relative change. Whatever amount the base rate is, it will increase by the same percentages.

The tl;dr of the chart is the most radical of the options (label rate returns to 55%, podcast dilution is removed from the royalty pot, a 25% increase in retail price and therefore royalties) results in a very meaningful uplift of 42% in royalties for artists from today’s current state. But, the three problems here are:

- Such measures could damage the commercial sustainability of streaming

- It does not change the underlying annuity model shift that streaming represents

- We are about to enter a recession. Music subscriptions are at risk, increasing the prices right now could accelerate subscriber churn. Meaning a bigger slice of a smaller cake for artists.

Let’s take the first two points in turn.

1) Spotify lost $184 million in 2019. With this royalty model it would have lost more than $1 billion. Spotify would have to reduce its operating costs by a fifth just to get back to losing $184 million. Critics would argue this represents trimming the fat. It might, but it would also likely lead to Spotify:

- Cutting back on product development

- Cutting back on growing its subscriber base

- Finding new ways to charge labels and artists for additional services

None of these are reasons not to pursue the strategy but they are prices that labels and artists have to be willing to take. Spotify revenue growth will slow. Furthermore, it will skew the market towards Apple, Amazon and Google who can afford to make music loss leading. In the mid term this may benefit artists, but in the longer term (i.e. when Spotify is sufficiently squeezed) these tech majors are likely to follow their MO of ‘reducing inefficiencies in the supply chain’. So be careful what you wish for.

2) Taking an artist straw person, with 20% of her total income coming from streaming, if live and merch only gets to 25% of its previous level, the 41% increase in streaming income would still see her total annual income fall by 40%.

No streaming lever can be pulled hard enough to offset the decline in live revenue.

So, let’s pull together all the pieces:

- Streaming royalties can be increased meaningfully if prices are increased and rates revisited but it may slow the streaming market

- Now is probably not the best time to be increasing streaming prices for consumers

- Even a big increase is not going to offset the fall in live income

There is not a simple, single answer to fixing the current crisis in artist income. A blended, pragmatic solution would be:

- Increase royalties at a middle option rate (do not increase prices until after the recession)

- Artists push their fans to buy their music at destinations like Bandcamp

- Professionalise and commercialise the livestreaming sector, with a strong focus on charging for events in order to create some live income

- Innovate virtual fandom products to drive new, additional income streams

It is not going to be easy for artists for some time yet. The hard truth is that income levels will not return to full strength until live does, and that is a way off yet. Streaming is more important now than ever so any solution must balance maintaining its momentum and scale with sustaining artist careers.