How Congress Can Right Wrong For Music Released Pre-1972

While the vast majority of streams for pre-1972 recording do currently receive some form of royalty payout from Pandora, a new bill recently introduced and known as the CLASSICS Act would ensure a greater degree of equality for all recordings.

__________________________

Guest post by Glenn Peoples, Music Insights and Analytics at Pandora of Medium

Imagine the uproar if digital music services chose not to pay royalties for some of the spins on their platforms. It certainly wouldn’t be overlooked by the music community. But this hypothetical scenario isn’t far from the truth, minus the services’ intent. Some spins are not generating revenue for the tracks’ rights holders and royalties for their performing artists.

Digital services aren’t the problem, they’re just following the law. But the law could change.

Enter H.R. 3301, also known as the CLASSICS Act (Compensating Legacy Artists for their Songs, Service, & Important Contributions to Society Act). Introduced July 20 by Reps. Darrell Issa (R-CA) and Jerrold Nadler (D-NY), the CLASSICS Act would create a new federal right for sound recordings released before July 15, 1972. With this new performance right, Congress would eliminate the demarcation line that has separated royalty-free music from royalty-earning music. Decades of recordings “have been hampered by antiquated and arbitrary laws,” Pandora general counsel Steve Bene said in a press release announcing the bill’s arrival.

Arbitrary is an appropriate word for current copyright law’s treatment of pre-1972 recordings. February 15, 1972 was the day Congress gave federal protection to sound recordings on a prospective basis while reserving recordings before February 1972 under state law. Years later, the 1976 Copyright Act gave recordings full federal protection — but only recordings made after February 15, 1972.

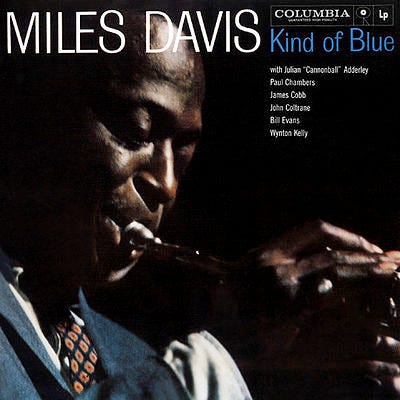

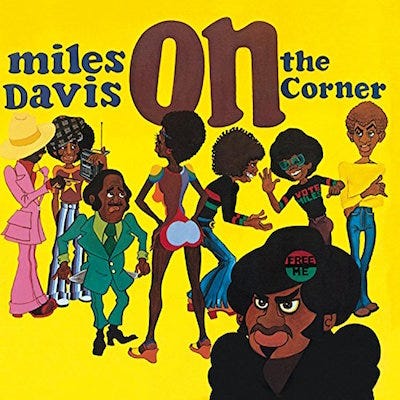

The decades-long recording history of jazz great Miles Davis provides a real world example of the pre-1972 issue. Davis’s recording history almost exactly straddles February 15, 1972 — his first and last albums were released 21 years before and 19 years after that date, respectively, although he released more recordings in the first half of his recording career. His 1959 album, Kind of Blue, the best-selling jazz album of all time, does not have the weight of U.S. copyright law behind it. On the other hand, tracks from On the Corner, released by Columbia in October 1972, through Davis’s 1992 posthumous release Doo-Bop have always been eligible to receive a royalty for digital performances.

Congress does some of its best work when it cleans up a mess. Well, the laws covering pre-1972 recordings are a mess. Without Congressional intervention, pre-1972 sound recordings will continue to be regulated, if at all, by various state laws. That patchwork legal regime has generated dozens of court cases and leaves open the possibility that a sound recording can be lawfully streamed in one state but not another. That is no one’s idea of a sensible system.

Efforts to update the law have been in motion for years. In 2009, the House Judiciary Committee asked the Register of Copyrights to look into the issue, give a recommendation on federal protection for pre-1972 recordings, and consider the effects federal coverage might have on preservation, public access, and economic impact on rights holders. The Copyright Office spent two years holding meetings and town halls to solicit input from stakeholders ranging from record labels to libraries and archives that preserve creative works. In the resulting report, The Copyright Office advocated federal protection that would cover digital performances of all sound recordings regardless of their date of release.

There are exceptions to the current rule. Pre-1972 recordings can receive performance royalties if digital services and record labels (or distributors) negotiate licensing agreements, usually called direct deals, that cover bothpre- and post-1972 recordings. Pandora has direct deals with the three major labels, independent rights group Merlin, and many other indie distributors.

Nearly all pre-1972 recordings in Pandora’s catalog can earn a royalty, but there are holes in the coverage because Pandora doesn’t have deals with every rights holder and distributor. Through July 13, there were 508 million spins of pre-1972 recordings at Pandora. Fortunately, direct deals cast a wide net and 91 percent of pre-1972 spins did result in a performance royalty.

Unfortunately, it’s the independent artists who are disproportionately affected by current copyright law. As Bene noted in his statement, “While many heritage artists are compensated through direct licensing deals, including by Pandora, it’s the independent musicians that this bill rightly protects.” Indeed, 4,600 album artists did not receive royalties for Pandora spins of their pre-1972 recordings through July 13.

Artists now deceased have been outlived by this quirk in copyright law. In many cases, these artists’ estates receive royalties from the sale of recordings and use in audio-visual works like motion pictures and television shows, but not performances of his pre-1972 recordings. The Miles Davis estate has protected his legacy by choosing how his music is may be used and who gets to make a movie about him (Don Cheadle starred in and directed the 2016 biopic Miles Ahead). But his estate hasn’t always received royalties for performances of all of his music.

The great Chuck Berry died in March of this year. His most popular songs — “Maybellene,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “Roll Over Beethoven” — were all released in the ’50s and ’60s. Over the years, Berry made a good living through touring, and he was fortunate enough to have written nearly all of his hit songs (compositions have a performance right). But Berry never earned performance royalties for those recordings. Nor has the estate of Buddy Holly, a contemporary of Berry’s who died in 1959, always received a performance royalty for his recordings. Holly’s widow has called the lack of federal protection “an injustice” that needs to change.

That about says it.