________________________

Guest post by Chris Castle of Music • Technology • Policy

Related articles

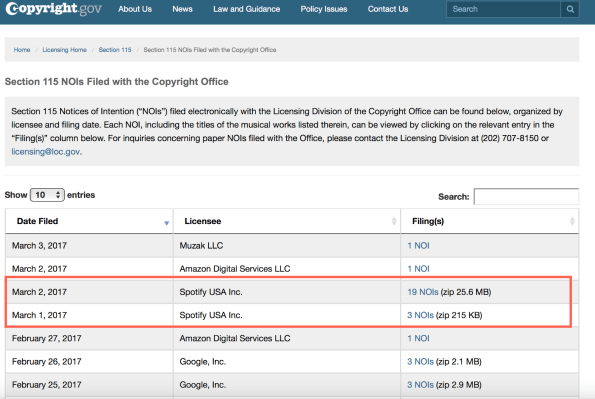

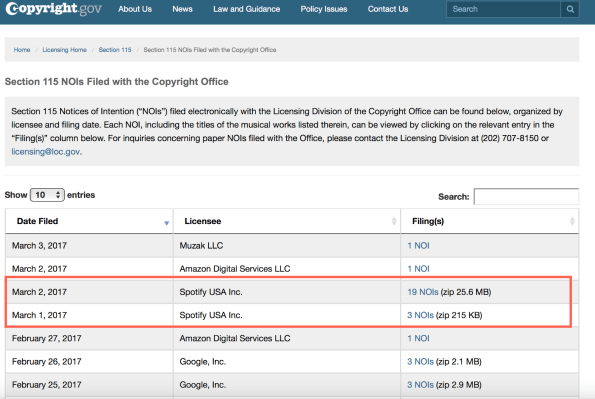

Spotify recently filed 217,112 "address unknown" NOIs with the U.S. Copyright Office saying that they were unable to locate any owner of these copyrighted songs anywhere in public records.

________________________

Guest post by Chris Castle of Music • Technology • Policy

Related articles