CDs As Expanded Instruments: Pioneers Of Hacked Sound Art

While compact discs are certainly on the decline as far as the average music consumer is concerned, several innovative pioneers within the music industry have and continue to explore the limits of the CD as not just a means of listening to music, but as a creative tool from which to create new sounds.

_______________________________

Guest Post by Jeremy Young on Soundfly's Flypaper

The Compact Disc (CD) was introduced into commercial ubiquity on October 1, 1982, alongside the world’s first-ever CD player, the SONY CDP-101. Billy Joel’s sixth studio album, 52nd Street, was selected to be the first recording issued on this new digital audio format, which is hilarious considering that particular album wasn’t even new at the time. 52nd Street was originally released in 1978.

CDs were developed over years of research with the intention of making recorded music available on an optical audio disc with superior sound quality. The audio division at Philips in the Netherlands is said to have first begun experimenting with the technology, however, SONY in Japan was supposedly also testing out optical discs, independently of Philips. By 1982, the two companies had joined forces to release the new medium to worldwide markets. One might say that the world has not been the same since. With all the conversations about sound superiority to vinyl, tapes and 8-track, laser and mini-discs aside, the compact disc has probably had the biggest influence on ushering in the vastly dominant digital music marketplace of today.

Since the prolific outbursts of the Fluxus movement, almost every popular medium of creative expression has been subject to artistic interception and recontextualization. In music, the influence of John Cage has led artists to continually search for expanded worlds of sound — new ways of expressing, creating, and listening to sound as music — in the generative possibilities of new technology [1].

Cage’s experiments with tape-collage and found sound, Christian Marclay and Milan Knizak’s use of turntables and prepared vinyl records and John Oswald’s practice of plunderphonics, among other working artists of the 1970s and ’80s, paved the road for reimagining the sounds of the medium itself as new forms of composition. Even photographer Lázsló Moholy-Nagy experimented with phonographs, imagining a way to “draw” the grooves to create a hand-written sound score.

While the work of these artists was almost exclusively considered avant-garde, eventually the cresting popularity and surge in production of electronic “glitch” music in the 1990s would solidify the explorative conquest of data-driven manipulations of digital technology as an important reflection of the way everyday consumers experience music.

Let me briefly digress to let tech journalist Eric B. Parizo summarize how the compact disc stores and converts binary data into audio: “A player uses a low-intensity laser scanner, reflecting light off of the surface of a disc. The code on the disc consists of flat areas and pits, or microscopic grooves. The intensity of the light reflected back from the surface of the CD differs depending upon whether the light strikes a flat spot or a pit. Electric signals are then created based on the varied intensity of the reflected light. Those signals are then amplified and interpreted in audio, video, etc.”

Error-detection systems were put in place so that small irregularities in the laser reflection would not affect the audio. In fact, this software was introduced and developed as early as 1960, so by the time home CD players made it to market, the programs were already pretty advanced. Roc Jiménez de Cisneros explains that the coding system essentially “guarantees that occasional scratches, dust or any minor imperfections on the data side of the disc do not corrupt information decoding, thus preventing them from altering the sound coming out of the speakers, which would potentially result in sporadic or even constant bursts of noise.”

Unlike vinyl and tape, to really “prepare” a compact disc requires a heightened sense of data-hacking, or at least, a much subtler hand at physical manipulation, in order to get past the error-detecting software and intervene with the data being read. Marclay has humorously stated, “I like the old-fashioned turntable… Because its so dumb. You can hit it, you can do all these things, and it will never stop playing. The CD players are too smart… smart machines” [2]. However, the end results of manipulating discs as well as CD player sensors, as we will see in the following artists’ work, reveal a glittering, unpredictable, and dense array of sonic possibilities.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “3 Artists Using Cassettes as Performance Instruments”

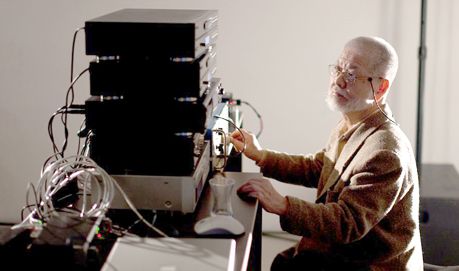

Yasunao Tone

Perhaps no artist has become the emblem for prepared, or wounded compact disc manipulations than Yasunao Tone. He was definitively the first artist to experiment with these processes; his work with the medium dates back to roughly 1984, a mere two years after the CD was introduced into the market.

Tone’s work is shaped by his focus on indeterminacy, or chance, which comes from being involved with the Fluxus movement in the early ’60s. He began poking pinholes in Scotch tape and sticking small pieces to the surfaces of compact discs in the mid-’80s, gauging the effect it would have on the players’ sensors [1]. Essentially, he found that although some of the binary data was being blocked, the machine still attempted to piece together the rest. So instead of shutting down, or skipping overany damaged audio, the CD scanned the audio as true, though it would not sound anything like the music contained on the disc. The result, as can be heard below, is like jittered white noise, dense with tones and rhythms contained in the original music, but fragmented and put back together like an audio puzzle.

Excerpt from Yasunao Tone’s Solo for Wounded CD (Tzadik, 1998)

Tone was improvisational in his performances with the wounded CDs. He would bang the CD players to get them to skip from place to place around the disc, which gave the listener a unique sense of the physical geography of the compact disc. Whereas you always know exactly where the needle is on a turntable, the compact disc sensor system is hidden inside the player’s internal hardware and is abstracted from the sound.

Yasunao Tone’s wounded CD (prepared with tape and scratches), photo by Gary McCraw.

Tone’s work, though decently documented on recordings, is predominantly based in the live andimprovised tradition. His interests have always been to create systems, or processes, by which data may be disrupted in the transfer from source to audio signal and to navigate these disruptions in performance. The following is a recording of one of his Mp3 Deviations pieces, which takes a similar approach to his work with CDs, but makes use of a custom built software that maps and interprets corrupted file error messages in MP3s.

Excerpt from Yasunao Tone’s Mp3 Deviations #6+7 (Mego, 2011)

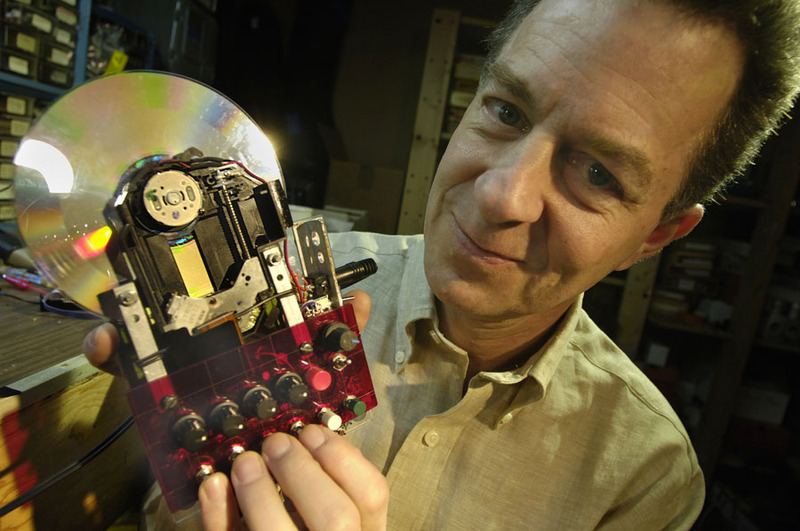

Nicolas Collins

Nicolas Collins is a multidisciplinary artist and electronic music composer, curator, writer, editor-in-chief, and organizational director. He does it all. Collins’ work in home-built circuitry and micro-computers was pioneering in the field of electronic sound art. His compositional practice is almost equally as important — his influence on the way contemporary composers use live technology alongside an acoustic orchestra cannot be understated.

His work with compact discs is not totally unlike Tone’s, in that there was a lot of trial and error experimentation to understand how the sensors inside the player actually functioned, and the boundaries of what they could handle.

It was through a hunch [1] that Collins discovered that the player’s chip contained a “mute” pin, which is perhaps the most important mechanism in the transference of coded data into audio. He removed the pin, and to his delight, the CD player just wouldn’t shut up. It translated every piece of information that the sensors picked up as audio, leaving no signals filtered. And this is where his work differs from Tone’s. Tone never really tampered with the player, just the discs, and while Tone was provoking the sensors to create sound, Collins’ work with this cracked medium is actually about controlling its silences. The piece below, “Broken Light” makes use of that very process:

It’s worth noting that this work is scored, even though by nature it involves an improvisational, reactional relationship to the piece on the part of the performers. Tone’s work is almost all solo or improvised without a score. The score to “Broken Light” is viewable here, and it is super interesting to read through. The image beneath shows what each string player was given, a hacked Sony D2 Discman, a modified remote control and foot switches to call up tracks for three movements (“1,” “2,” “3”), scratch across CD (“S”), and nudge through tracks (“N”).

Collins was a student of Alvin Lucier at Wesleyan, where he was able to meet John Cage, Christian Wolff, David Tudor, Robert Ashley, Gordon Mumma, and others. In New York, he was part of the Impossible Music Group, along with David Weinstein (one of the founders of New York’s Roulette Arts Intermedium and a producer of Clocktower Radio), which performed works for cracked media, often including several prepared CD players.

Collins also invented a multitude of instruments like the backwards guitar, the MIDI trombone, and through his tinkering with the mute pin, the unmuted CD player. Collins got the chance to showcase the MIDI trombone in every track on his album 100 of the World’s Most Beautiful Melodies, which featured duo improvisations with John Zorn, Elliott Sharp, Peter Cusack, Christian Marclay, Shelley Hirsch, and so many others. And because Collins is not shy about anything relating to his process, he also wrote an essay on how the sampling trombone device works!

Read more on Flypaper: “Elliott Sharp’s Essential Guide to Being Elliott Sharp”

Oval

Oval was a musical project initiated in Germany in 1991 by Markus Popp, Sebastian Oschatz, and Frank Metzger, although now only Popp (pictured above) remains connected with the group. Their early albums Systemisch (1994) and 94Diskont (1995) were hugely influential in solidifying the new electronic sound known as “glitch.” You’ll notice immediately how different Oval’s music sounds from the others in this article, in that this is actually quite pleasing!

Systemisch contains hundreds of samples generated from scratched and written-on compact discs, skipping and failing. But the group edited them into minimalist, pretty rhythmic grooves and tones,using them as source material for what today would be considered your basic electronic track. All of the typical CD stuttering sounds, seem to be rounded off, EQ’d and compressed into drum-like tracks that reference the standard sounds off a drum pad.

Funnily enough, the band actually started out as more or less pop music, writing instrumental and vocal music in the late ’80s. Disdaining the use of synthesizers, Oval instead deliberately mutilated CDs by writing on them with felt pens, then processed the palette of fragmented sounds to create a very rhythmic electronic style. Early digital drum and loop sequencers with interactive interfaces like Cubase were just coming into the market in the early ’90s. Looking back on his process, Popp recalls,

“Essentially, I was looking for new musical building blocks without relying on quantized MIDI sequences plus, say, a drum machine. And the most interesting and unpredictable sequences I could find was the fascinating, irregular musical ‘storytelling’ of a laser of a CD player skipping over the damaged surface of a compact disc. So one could say that the early Oval signature sound ended up mainly consisting of re-composed fragments of (what once was) other people’s music not because I was ‘anti-music,’ but because this was simply my best (low budget) shot at an electronic music that was new and surprising as opposed to being purely experimental.”

Oval’s album 94Diskont (1995)

Later, through experiments in sampling and controlling the stutters into more predictable rhythmic patterns, Oval stumbled into the beautiful “glitchy” minimalist electronic music for which they have since become known, sampling errors into beautifully imperfect patterns. They have influenced artists such as Autechre, Björk, and one of my favorite sampling albums of all time, Jan Jelinek’sLoop Finding Jazz Records (2001).

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Sampling as Instrumentation: How Recorded Noise Found Its Way into Music”

Others

On the 2001 compilation album, Un Tributo to James T. Russell, the Spanish imprint Alku collected tracks from a range of artists using hacked compact discs to create an ironic tribute to the founder of the CD itself, Mr. Russell. You can stream the entire album at Francisco López’s SONM Sound Archive of Experimental Music and Sound Art for free, though you need to register. Tone and Oval are both represented here, but some of the other highlights include a work by Javier Hernando, where he records himself back-skipping over a CD’s contents, and 35 consecutive 4-second tracks, all completely silent, by conceptual artist Terre Thaemlitz which open the album with a Cagean listening exercise — coercing the listener to take note of the audible noise their CD player makes while playing this very disc.

The compact disc is now 33 years old. There are of course, tons of contemporary artists out there experimenting with sound collage, sometimes including samples generated from CDs, CD players, and hacked lazer-read media. At the heart of many of these artists’ work is either the drive to create new sonic systems and landscapes from altering the way data is communicated from source to signal (Florian Hecker and Ken Gregory for example), or an intent to draw the listener’s focus towards the medium and its properties as a sound-generating device (like Otomo Yoshihide and hiswork with Sachiko M, and Zorn affiliate David Weinstein).

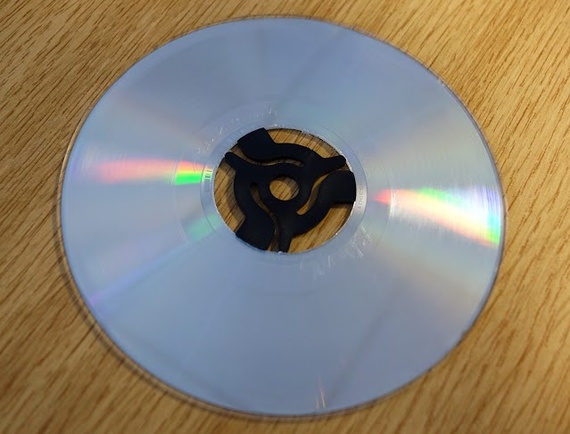

This disc still looks like a CD, but it plays like a record. (By Amy Freeborn)

London-based sound artist and designer Aleksander Kolkowski has created a way to lathe-cut vinyl grooves onto the surface of CDs, making them playable on turntables. That’s pretty much the ultimate put-down for a medium that for so many years was advertised as “Perfect Sound Forever,”and reminds us of one of Nicolas Collins’ famous statements: “music isn’t just conveyed in grooves, pits and waves. Music is grooves, pits and waves.”

Update: This article was updated on April 5, 2016 to include quotes from Oval’s Markus Popp.

—

Notes

[1] Stuart, Caleb. “Damaged Sound: Glitching and Skipping Compact Discs in the Audio of Yasunao Tone, Nicolas Collins and Oval.” Leonardo Music Journal Vol. 13: Groove, Pit and Wave: Recording, Transmission and Music (2003): 47-52. Print[2] Marclay, Christian and Tone, Yasunao. “Record, CD, Analog, Digital.” Audio Culture: Readings In Modern Music. Ed. Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner. London: Continuum, 2004. 341-347. Print.

Very cool article!

Thanks for the article.

I vivdly remember putting a CD-ROM of Microsoft Word into my uncle’s ancient CD player from 1983 at some point back in the late 90s, and it indeed played the data content as sound: A brash electronicly sounding “hum” relatively quickly gave way to a white noise resembling sizzle which would have lasted throughout the “album” but got boring rather rapidly.

interesting article.

Quite entertaining and educational article. Thank you.

Good article, though it’s missing this beautiful piece from 1987(!) by Steve Layton, “Socrate gloss: Bords de l’Ilissus.” Get the mp3 here at:

http://www.niwo.com/steve/music/Mp3workspage2.html