By Eric Peckham on Medium.com

The evolving music industry is turning top managers into moguls—operating across media, tech and consumer brands The evolution of the music industry is putting greater power into the hands of top artist managers and transforming their firms—traditionally very small, behind-the-scenes operations—into miniature conglomerates operating across media, tech, and consumer brands.

The root of this transformation is the broader shift in power from labels to artists, and thus to artists’ management teams. The internet empowers artists with the ability to directly engage fans and distribute digital content on their own, a dynamic that has made record labels—whose deals usually give them the majority of an artist’s music revenue—increasingly less necessary for building a national, or even international, audience.

The whole EDM genre, which has been on fire over the last few years, has thrived largely without major labels or radio. In hip-hop, Macklemore & Ryan Lewis (with manager/agent Zach Quillen) built a passionate fan base locally and online, leveraged that to run their own (profitable) tour, reinvested earnings to self-finance the production of the The Heist, and then went to labels only later with the negotiating power to strike a la cartephysical distribution and marketing deals.

Even in the more common arrangement of taking a traditional record deal—which remains the norm and likely will for many years—top artists and their managers have been faced with an increasing hand-off of responsibilities as the labels downsize their investment in developing artists (mainly because they themselves are tight on money). Management firms, talent agencies, and publishers are in response expanding to handle many functions that were traditionally label services.

As a result of both trends, power is shifting into the hands of artist managers and their teams, who are at the helm of an artist’s whole operation as a business… which keeps expanding in scope.

Artists as Diversified Brands

An artist manager’s job description nowadays goes far beyond merely coordinating a musical career.

This is partly by force and partly to take advantage of new opportunities. Although there’s some optimism for earnings from streaming services to improve as their use becomes ubiquitous, revenue from songs themselves is no longer very significant in comparison to how popular the songs are and what album sales would have once brought in at that rate.

Music (and social media presence) is the heart and soul of who an artist is and where they devote their time, but its function from a business lens is just the starting point. It fuels a brand and loyal audience that are then leveraged for complementary ventures with more meaningful money-making potential.

Coordinated mostly by an artist’s agent, the live music (touring & festivals) boom has combatted losses in music sales and continues to see healthy growth—a unique in-person experience remains well worth paying for—but it’s only one piece of the puzzle.

New forms of collaboration with brands are a central revenue source and require a broader business and digital savvy from the artist manager to envision and evaluate opportunities effectively. Traditional sponsorship deals remain standard, but in increasingly creative (and often complex) forms like Pepsi’s “tweet to unlock” campaign around Katy Perry’s Prismalbum, the Jay-Z/Microsoft collaboration for launching his Decodedautobiography, or AmEx’s interactive “Blank Space” app with Taylor Swift.

But there’s also an evolving shift toward longer-term, equity-based partnerships. Rather than “selling out” by slapping their name on lots of random products, artists are finding corporate partners whose brands genuinely complement their own, then working to help build the product/company over time and share in the upside, like Pharrell’s work with sustainable materials brand Bionic Yarn. If the artist manager has the eyes of a smart investor, equity-based deals can be dramatically more lucrative for artists: 50 Cent’s (estimated) $50MM stake in Vitamin Water, and Diddy’s 50% profit-share in Diageo’s Ciroc vodka, sparked wider adoption of the model in particular; Justin Timberlake’s stake in the relaunch of Myspace, not so much.

Especially after its recent $3B acquisition by Apple, Beats by Dre stands as the pinnacle example of a how artists might parlay their personal brand into their own startup companies

Most notably, as a step beyond equity-based partnerships, popular artists are increasingly channeling their personal brand into the launch of their very own companies, matching creative control with far more potential upside. Madonna’s launch of Maverick in the early 1990s (with music, film, tv, book publishing and fashion divisions) was an early incarnation of what really took off among hip-hop icons in following years (although she’d go on to add more fashion lines and an international fitness club chain in 2010 as well).

Jay-Z (Roc-a-Fella Records, Rocawear), Diddy (Bad Boy Entertainment, Sean John, Revolt TV), Pharrell (Billionaire Boys Club), Dr. Dre (Aftermath Entertainment, Beats by Dre) and others have capitalized on the opportunity to build successful companies rather than just being a marketing tool for others. Even in country music, Kenny Chesney co-founded a successful spirits company, Fishbowl Spirits (maker of Blue Chair Bay Rum), built from scratch entirely around his brand and audience demographic.

Artist Managers Take Center Stage

In this new landscape, top artist managers are full-scale entrepreneurs building conglomerates spanning media, tech and consumer brands.

One part venture capitalist, one part entrepreneur, a manager is on the hunt for “the next big thing” in music to invest their efforts in—informed by an increasing amount of data and knowing that inevitably most “investments” won’t be big wins (managers, by the way, get a roughly standardized ~15% of artists’ earnings). They’re in charge of launching those artists to become an internationally-known brand in the span of just a couple years and gradually crafting sustainable businesses underneath them.

Kara Swisher interviews mega-managers Troy Carter (Atom Factory), Scooter Braun (SB Projects) and Guy Oseary (Maverick / A-Grade) at D11. Great example from Braun on artists as consumer brands: at the time, the #1 and #3 top-selling perfumes globally were both Justin Bieber-branded ones

The tools and strategy needed to break an artist into stardom in 2015 often look more similar to operations of Silicon Valley startups—social media buzz, extensive analytics and key partnerships. The more capable an artist manager is as a digital entrepreneur, the farther the artist can go without needing the support of a record label at undesirable terms. Thus it’s not just increasingly necessary but also preferable for the artist and manager to build out the management firm’s team and handle operations across music, partnerships, and new ventures themselves.

As the management firm’s capacity grows, it also makes sense for it to take on additional artists, given the economy of scale. The management firm becomes a whole funnel for launching new artists and coordinating their stakes across numerous ventures. They can plug their artists into a network of opportunities they’re pursuing and ventures they control, cross-pollinate fan bases strategically, and collaborate with their established artists to propel newly-signed acts into the spotlight (look at how Justin Bieber put Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe” on the map).

The result of it all is a much more influential and—contrary to their historic place—high-profile role for leading artist managers within the entertainment industry and beyond. It also makes the choice of manager a much more important, longer-term decision for an artist than it used to be when labels did more of the work and managers were switched out like pairs of socks.

Artist Managers as Media Moguls

If you extrapolate another step, what top artist managers (and their teams) are really becoming are experts in identifying, launching and operating creative business ventures. It hasn’t taken long for them to realize that they can apply their skill set beyond just musicians.

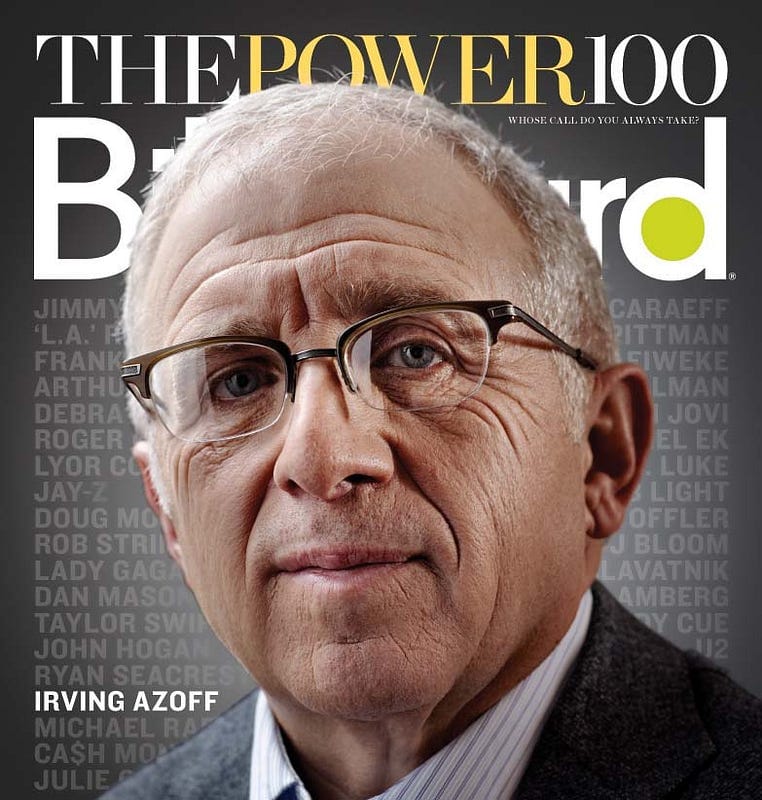

Within entertainment, social media stars, actors and other talent are getting added to management rosters: look at Irving Azoff’s work with comedienne Chelsea Handler and investment in Levity, the recent merger of Primary Wave and Intellectual Artist Management, or SB Project’s management ofTodrick Hall.

Tech entrepreneurs, in particular, are the new cool kids, and top artist management firms (not to mention talent agencies and labels) are interested in the action up north in Silicon Valley. Troy Carter (Atom Factory), Guy Oseary (Maverick / A-Grade), and Scooter Braun (SB Projects) all raised venture capital funds to apply their particular business savvy (for marketing, pop culture, media platforms and consumer trends) toward lucrative investments in startups like Uber, Airbnb and Songza. They’re still an anomaly in the startup world, fulfilling a new niche of “Hollywood VCs” and providing enough differentiated value to access some of the most competitive deals, typically invited in by the lead investor. Some tech investments are media-related but many aren’t—it’s not so much about strategic investments that impact their artist management responsibilities as it is about diversifying the types of creative, consumer-facing ventures their firm can advise and build a stake in.

As they get more comfortable bridging industries, several of these top management teams are also applying their experience in launching artists and advising startups to the incubation of their own tech products and consumer brands as a new revenue source (just like they’re doing for some of their established artists). Atom Factory co-founded Backplane and Pop Water; SB Projects incubated fahlo and relaunched British Knights; Azoff MSG has been on a buying spree across entertainment and media; and Red Light Management’s Coran Capshaw previously launched and sold e-commerce platform Musictoday. Each firm has even brought creative studios in-house.

This new model has the firms split between managing talent, launching new ventures and investing in outside opportunities, with each pillar tying into the others. It’s like an entertainment industry keiretsu with one management/investment team at the center of a network of interrelated businesses.

Not all managers can or will follow the same business expansion beyond what relates directly to their artists, but even that still requires a wider scope of business savvy than ever before—spanning music, tech, and brands. Agencies and publishers are adapting as well to handle operations that shift away from labels, even hiring their own radio promotion staff, and will be resources to small management teams that don’t yet have the capacity to handle such a wide scale of new responsibilities.

It’s still early in the game, but the evolving role of management teams will likely change the working (and perhaps even financial) relationship between artists and managers, leaving many questions about where labels fit in. This evolution finds top music managers well-positioned as a new form of media mogul.

For more from Eric Peckham, follow him on Twitter @epeckham

Related articles