The Paradox of Music: Is More, Really Less?

Kyle Bylin, Associate Editor — (@kbylin)

I. New Choices

Often times, in discussions about how our culture has become abundant with music and the potential that it has to cause choice overload in the minds of fans, it does not take long for someone to recall the amazing lecture that psychologist Barry Schwartz gave at TED back in 2005, where he explores the central thesis to his book The Paradox of Choice. Let us use his talk as a starting point for this conversation and try to figure out if the effects of the culture of abundance that he outlines in it also relate with the perils that we suspect fans experience in the digital age. In doing so, we will get a better idea if fans may fare worse and be robbed of satisfaction in a culture abundant with music.

In Schwartz’s opening statements, he presents what he calls the “official dogma” of all western industrial societies, which, in his mind, goes something like this: “if we are interested in maximizing the welfare of our citizens, the way to do that is to maximize individual freedom,” and the way to maximize it, he argues, is to "maximize choice." He sums up his thinking on this issue, by saying that: “The more choice people have, the more freedom they have, and the more freedom they have, the more welfare they have.” No one would argue against the idea that in order to have a sustainable, healthy, and lively music culture—there needs to be diversity. This idea states that the more music options people have to expand their taste with, the more cultured they turn out to be. As a result, it could be said that society, as a whole, is better off; its citizens—having experienced this multitude of perspectives, life experiences, and views of the world—are marked by the refinement in their taste and knowledge.

"fans could wade through the plethora of music that had risen through the bottom-up participatory culture of the Internet."

Indeed, throughout the last decade, fans have experienced the splintering of genres into niches and an explosion in music choices. As our current logic would tell us, this is a good thing. Rather than being limited to the top-down, corporate created music that the record industry provided, fans could wade through the plethora of music that had risen through the bottom-up participatory culture of the Internet. So, too, during this time, the media landscape fractured into pieces and fans witnessed the rise of the personalized music experience. Now, each fan could find a media outlet that more perfectly matched their taste. Hell, if they wanted to, they could even create their own stations on sites like Pandora and Last.fm that were specialized to their taste—no matter how arcane. Also, fans could download whatever music suited their interest—for free—and edit out every moment of their musical experiences that did not suit their needs.

Thus, much like the proliferation of choices in the supermarket, careers, and consumer electronics that Schwartz goes onto describe, fans have experienced a similar revolution. Both in terms of what fans consume and how they consume it, the amount of choice that each of fan encounters has greatly increased in a short number of years. The paradox of music choices though, is that while the number of options that a fan faces in the physical world has contracted, due to shrinking of shelving space devoted to music in retail outlets, online, the amount of music that they can experience has exploded. What’s paradoxical about this situation is that judging by decreasing diversity of commerical radio stations and the drastically reduced selection in music departments; a coming of age fan might be left with the overwhelming sensation that there is less music available today. When in fact, there is actually more music being made available now than at any other point in the entire history of popular music.

II. The Tyranny of Choice

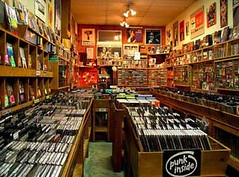

No doubt, many of you are old enough to remember what it was like to purchase music before the Internet, the epidemic of file-sharing, and the fracturing of the album format. Likely, some of you even spent a few the early years of your career working in a record store. The selection was vast, but not so much that it was overpowering, and if a fan did need some assistance in navigating these choices, there was probably a clerk like you to offer them a bit of sage advice about what music they might like. Whether or not they listened to you, of course, is another story entirely. Even so, since we all seem to know what’s good about a record store full of music; let’s talk about what is bad about it.

At this point in Schwartz’s lecture, he makes the argument that in this culture of abundance, “All of this choice has two effects, two negative effects on people. One effect, paradoxically, is that it produces paralysis, rather than liberation. With so many options to choose from, people find it very difficult to choose at all.” In effect, the more albums that a fan is attempts to choose from, the more likely they are to either kind of freeze up and go with the path of the least resistance, like the lastest pop album, or to simply leave with no albums at all.

“The second effect,” Schwartz says, “is that even if we manage to overcome the paralysis and make a choice, we end up less satisfied with the result of the choice than we would be if we had fewer options to choose from.” Why is that?

Well, there are several reasons to make note of: First, when a fan goes into a record store that has thousands of albums to choose from, if they buy one, and it’s not what they thought it would be—after all, what new album is? Schwartz explains, “It's easy to imagine that you could have made a different choice that would have been better. And what happens is this imagined alternative induces you to regret the decision you made, and this regret subtracts from the satisfaction you get out of the decision you made, even if it was a good decision.” In this line of thinking he further contends, “The more options there are, the easier it is to regret anything at all that is disappointing about the option that you chose.” Fans are candidates for regret when they buy an album and it turns out to be either not what they expected, or not as good as they expected. Also, they are primed for regret when they purchase an album and, soon after, realize that they could have selected a different album that sounded better.

"The more that a fan considers these other songs, the more their satisfaction with the final purchase is diminished."

Next on the list is what economists call “opportunity costs.” These are, in respect to music, when there are lots of alternative albums to consider in a fan’s purchase—given that they are a somebody with limited funds, and have to be satisfied with this album; it’s easy for them “to imagine the attractive features of alternatives that [they] reject, that make [them] less satisfied with the alternative that [they’ve] chosen.” Even if the album that the fan chooses happens to be one of the best that they have heard, it is exceedingly likely that many of the passed up albums also contained several fantastic, brilliant songs on them too; ones that they had to go without. The more that a fan considers these other songs, the more their satisfaction with the final purchase is diminished.

Third is the escalation of expectations. “With so many options to choose from,” Schwartz writes, “it is hard to resist the expectation that what one finally chooses will be perfect, or at least, extraordinary.” When a fan is shopping for a new record and all these albums are bouncing around in their head, yet they can only buy one; it is entirely possible that their expectations for how good that album should be, go up. By the time the fan does put the CD in their player, experience of it and the amount of satisfaction they derive is lessoned. In a sense, the CD they bought is disappointing in comparison to what they expected. Perhaps what happens when a fan encounters this surplus of music is that all of these added options increase the expectations that they have about how great these artists and their albums should be. “And what that's going to produce,” Schwartz further clarifies, “is less satisfaction with results, even when they're good results.” Put differently, it’s possible that the good album was really a great album.

Furthermore, for previous generations, one consequence of buying a bad album when there were not that many available is that when a fan was dissatisfied, and they asked why and who was responsible, the answer was clear. The record industry was responsible; they put out a bad album and made a misjudgment about its quality. Since both the fan and their friends listened to the same music, it was a more of a reflection of the quality of music available at the time and not of the quality of their taste. When there are thousands of albums to choose from in the record store, there is no excuse for failure. “And so when people make decisions, and even though the results of the decisions are good,” Schwartz explains, “they feel disappointed about them, they blame themselves.” The industry did nothing to the fan, they did it to themselves.

III. Why Culture Might Be Different

The corollary to the effects of choice overload in the domain of music, and perhaps cultural objects in general, is that, unless the limitations of a fan’s disposable income do in fact force them to be selective when they purchase music, buying one album doesn’t necessary mean not buying the other. Although they may still experience a degree of anticipated regret or buyer’s remorse, it is likely that it would not be too severe. Granted, that does not mean that satisfaction that they get out of the album they did buy—even if it was a great album—will not still be lessened as a result. Whether the fan is conscious of it or not, the experience they have of that collection of songs will be dampened more than it would have, had it been the only option they considered—resulting in a decrease in their overall satisfaction.

Then again, it could be argued that most fans do not truly experience the entire selection of the record store anyway. By the time they can afford to purchase music their taste has already been refined. Plus, while a fan may notice an unusual artist name or some remarkable cover art, they may not know who the artist is or if their style exists outside of their preferences, so these additional options would go mostly unnoticed. Since radio and MTV played such a vital role in promoting music in the pre-Internet era, and a great number of the titles carried by the store reflect their playlists, most fans had enough familiarity with a small cache of artists already. Again, this had the effect of dramatically reducing the amount of choice that each fan experienced. Thus, while a fan may have felt many of the symptoms that we associate with choice overload, it is hard for us to know how great of an impact it had on their music experience and to what extent the amount of their satisfaction with it may have been reduced.

"The paradox of choice is simply an artifact… of the physical world…"

However, anyone who has read Chris Anderson’s book The Long Tail would remember that he does not necessarily agree with the arguments made by Barry Schwartz. In the chapter titled The Paradise of Choice, he writes, “The paradox of choice is simply an artifact of the limitations of the physical world, where the information necessary to make an informed choice is lost.” From his point of view, “The paradox of choice turned out to be more about the poverty of help in making that choice than a rejection of plenty. Order it wrong and choice is oppressive; order it right and it’s liberating.” In other words, sure, in the record store, when faced with a large array of albums, fans may feel discouraged, but in an environment like Amazon, the selection process is easier. Fans have more information to take into account before making a decision and various ways to segment the current array of options into categories that are more meaningful. Also, if they get stuck and need a little extra help, the recommendation engine is there to further simplify the number of albums they have to choose from; it presents them with the albums that “people who bought this album also bought.” Therefore, due to the way Amazon eases the selection process, it’s likely that the amount post-sale regret that a fan experiences will be minimal. “After all,” Anderson reasons, “if everyone else picked a given product, it can’t be that bad.” Still, as it is with anything else, we will see if there is more to it than that.

In research paper published shortly after The Paradox of Choice, Schwartz points out that almost all the research that has been done on ‘choice overload’ has involved some kind or other of goods and services. “Though,” he says, “I don’t for a minute believe that choice overload is restricted to the material domain… it is important to ask whether there is something about the world of culture that makes it different.” To which he then asserts, “I think there are reasons to regard culture as a special domain, and I also think that the profusion of cultural options has positive externalities that make it good for society even if, at the same time, it adds to the frustration and confusion faced by individuals.” The thing is, he writes, “Yes, we all have limits of time and financial resources, but cultural objects and events are not substitutes for one another to the same degree that ordinary material objects are. Perhaps because culture is an ‘experience good,’ participating in cultural events may whet the appetite for more participation. ‘Doing’ culture may stimulate demand for more culture. This may be enough, in and of itself, to make choice in the domain of culture an unalloyed blessing.” To conclude: no. In the physical world, more music is not less—that even if the abundance of choice available to fans decreases the amount of satisfaction they derive from their music purchases; the social ecology of our music culture, collectively, will be better off. The benefits outweigh the drawbacks. Yet, these two viewpoints still leave a question left unanswered: Has the Internet actually created a paradise of music choice? Or, does it too have paradoxes?

Contact Me:

- kyledotbylinatgmaildotcom

Related Reading:

Photo Credit:

- (Top-Left) maol

I am a Fort Worth DJ and here here many different songs everyday. The problem is that everything is starting to sound the same.

Peace

Fort Worth djs

http://www.mygoodtimesdj.com

The internet, I believe, one day will become the cloud for all sound. Sadly, at the moment, a lot of music hasn’t even reached the vinyl or CD stage. Paul Young’s classic novelty hit ‘Toast’ under the moniker Streetband is still unavailable through download. Yeah, this is closer to the thin end of the tail but still a valid and possibly lucrative point. Many many recordings still languish in an obscure and lost void. It’s here that many P2P’s thrive and clean up in this area. Only research, investment and support into the complete digital migration, harmonisation and preservation of music can resolve and improve this sorry state of affairs. The internet is not yet a paradise, however, it can be a better library and repository for all sound.

Phew, some really, really good points there. It got me thinking about the trend towards bespoke services and whether there’s an inherent flaw dependent on someone’s personality type. For example, last.fm, yep, you can completely customise your playlist so it’s perfectly ‘you’……and then you don’t want to listen to anything on it. That leads on to the line about ‘poverty of help in making the choice’ which is just sublime. Whose opinion do you trust? Ten people on Amazon can rave about an album that you still might not like……even if on paper (so to speak but more so on screen these days!) it fulfils all your supposed criteria. It’s like preferring Van Halen over Motley Crue back in the day 😉 I know we’re focusing on music here, the enjoyment of which is of course entirely subjective, but I wonder about the wider implications in the sense of, theoretically:

Everybody can infinitely customise every aspect of their lives so that they are identifiably and uniquely ‘themselves’. But…..they don’t like it. They feel alone and would rather be ‘a part of something’ and have some sense of community.

The talk of paralysis resonates; deciding which retailer to use to buy an external hard-drive, a hundred choices, all a similar total price regardless of the product and postage options!

Before I ramble on I think ultimately, yes it is a paradise of choice, it’s just that having all those choices might have unintended consequences.

Devo said way back in 1980: “Freedom of choice is what you got. Freedom from choice is what you want.” And how many more choices do we have today than we did 30 years ago?

I still believe there needs to be taste makers or aggregators to serve as a filter between all of the music and the fans. There is a lot of bad music out there and you need to find the hidden gems and get them to the forefront. The downside of the internet is search can take a remarkably long time, you either have to listen/scour music blogs or internet stations, or sift through amazon recommendation pages which has it’s limits. I started a website http://www.fuzzedout.com because of this very problem, it’s just a service I would want as a music lover.

Great article! I’ve read this twice. The arguments you make really hit home. You’ve added some science around why some people just pirate. There’s too much to sample and the price tag is too high to see if you like the “Top 100.” There has to be a middle ground for music consumers. Perhaps Pandora and Jango (I’ve found really great artists on both sites) could improve on their model. I know if a track catches my ear a few times, it’s a good decision for me.

Well done on the article — loved it.

Deborah

Relatively few people will listen to everything to find the gems. Most of us don’t have the time or the interest. We still have people who review quite a bit more than the average listener, but it is likely they still miss stuff.

If we wanted to harness power of the network, then perhaps we would have groups of skilled listeners who would each listen to at least ten albums a week and if any of the albums are any good, they could put them into a recommended list. And then those lists could be screened until we reduced and shared our favorites down to a fairly widely agreed upon top 100.

We have that after a fashion in that local bands submit their albums to local reviewers. If an album creates a buzz within its local community, then the word spreads and reviewers in other communities check it out, and if enough of them like it, then the word gets around until it reaches a national level.

I think you’ve got to the heart of the paradox there. Part of the argument ‘for’ the internet (as far as music’s concerned) is that it ‘levels the playing field’. A lot of the ‘new industry model’ musicians and bands that are doing it all by themselves (me included) are able to distribute their material in ways that were impossible in the past. Which in principle is great if someone comes across it and thinks it’s a hidden gem.

However, if you go searching for a hidden gem and find nothing but a million bands that you think are shit, you end up sat there thinking ‘I wish there was some way to filter out all the crap’…….which is sort of what the big record labels used to do, if it sells it’s great music, if it doesn’t it isn’t. But, that’s the thing that people wanted to get away from because they were fed up with what the ‘gatekeepers’ were giving them, effectively saying ‘just because it sells a gazillion copies, doesn’t make it any good’.

It’s an over-simplification but you get my point 😉

It just depends on your opinion, which these days everyone has. Have you read ‘The Cult Of The Amateur’ by Andrew Keen? He discusses this sort of thing at length and basically summarises that the democracy inherent in the internet has, overall, been a bad thing for culture as far as quality control is concerned.

Part of me agrees and yet here I am in principle, adding to the problem. Funny old world!

I think you’re right Suzanne. The ‘old’ perception used to be that if you were ‘unsigned’ or not creating a buzz then there was a reason i.e. you weren’t good enough.

That is still true though I think the perception created by the internet is that it isn’t, which is foolish at best 😉

Your last paragraph is interesting because I think a lot of people no longer consider ‘local’ interest to be relevant. If you live in Iceland but have made a ton of fans in Japan, local & community become different terms from how we used to use them.

I think you’ve got to the heart of the paradox there. In a sense the old idea of record labels used to be that filter, which is what people wanted to get away from because they were fed up with what the ‘gatekeepers’ were feeding them.

It depends on your point of view, if you find a hidden gem then it’s great and the new democracy works. If you’re sifting through a ton of bands that you don’t like then it doesn’t.

I can understand that we have moved beyond a local audience, but local reviewers are still more likely to check out bands from a certain area than other reviewers.

If you are an emerging artist/band, you’ve got to break in somewhere. If you are skillful, you might be able to develop enough of a rapport with bloggers or fan groups in some distant land who will then pay attention to you. But otherwise, it’s your local community that is most likely to check out your new CD.

Let’s just say this: With millions of bands clamoring for attention, how to you get a foot-in-the-door? Do you do the old MySpace technique of saying, “If you like Band X, check out my band.” How many of us really pay attention to a pitch like that?

Maybe if you pay some decent money to a producer or a recording studio, then producer or studio might recommend you to their industry contacts.

Or maybe you hire a radio promoter or publicist who uses their network of contacts.

Seems to me that working the local market first is still the best, cheapest way to go for most bands.

The thing about the old system was at least we understood it. You made a demo. You tried to get it to the right people. If people liked it and thought you had commercial potential, you got a record deal.

Most people who had those deals still didn’t become megastars, but at least there was a system.

Now it’s anybody’s guess. For awhile people thought if they got their MySpace numbers up, that would lead to success. But then we found out (1) people were gaming the numbers and (2) MySpace fans aren’t necessarily buying fans.

Now we are focusing on YouTube. Yes, getting big numbers of YouTube seems like a good thing, but there’s still the question of whether people who watch your videos will come to your shows and spend money on you.

If success in the music business means doing the right things in order to make a living wage at this, most people still haven’t figured out how to do it. There’s still a disconnect for many bands between visibility and making money. In fact, there are likely local bands that no one outside their communities have heard about who make more money from music than some of the emerging buzz bands.

I agree, I just think the net can be perceived as promoting the idea that it’s not the case. The old method of getting out there in front of people is still the best way, especially as the trend towards the live ‘experience’ continues.

I think what I am talking about is word-of-mouth. How do you get people talking about you and recommending you.

Having someone see your live show and then bringing friends to your next show is probably the single best way to go, which still tends to start locally.

The next best might be to have a YouTube video and have people forward it. I think artists have caught on to the fact that the best way to have random people trip over your video on YouTube is to cover a famous song, and then people see it when they are searching.

The hardest might be to get your song heard when no one besides friends/family has ever heard of you. I guess if you can get your song into a contest and have your friends vote you up, so that you rise to the top and then people will see you. Or maybe getting your song into Pandora where it comes up as a recommendation.

Of course, there are other tricks, like doing something geeky and then getting written up in a tech blog for that. Or doing something that gets you into some other type of non-music blog and then people check you out.

” if you were ‘unsigned’ or not creating a buzz then there was a reason i.e. you weren’t good enough.

That is still true

”

I disagree… Its all about hype, looks, and the right product. PRODUCT. Look at the charts. You’re telling me Kesha, Justing Beiber, the Jonas Brothers and Miley Cirus are talented? They are the best? They are signed because they are good?

Get real… Buzz are created most of the time, they aren’t legit. I know several artists who aren’t popular but could play circles around stars.

As a Musician,Songwriter,Producer Engineer, I can honestly say that there are a couple things that the industry needs to wake up on , one is that what makes a star is the artist that has the talent and can pull it off live No playback. The Greed part of the industry started to make instant fake stars for profit that eventually this stars fall for there lack of talent and the fact that real fans that by the ticket to see these star expect the talent they are smarter than industry gives them credit.

Two while ipods and mp3 players have become the norm and easy to transport , the fact is still today in a professional studio we hear a mix quality that is yet to be transfered to the consumer public . The Audiophile public has been forgotten and the quality and dynamics of digital while it has improved is not at all what a consumer can enjoy nor is the industry trying to eduacate the public of what real dynamics and warmth can bring to their music.

So until the industry can realise that not only the teenagers , the 20, 30, somethings and older love true talent it will be questioning it’s own questions.

Hi Bob, I know what you’re saying, that’s why I said “The ‘old’ perception used to be that…..” That was my disclaimer though clearly that was not, er, clear.

If you actually get to hear someone (especially live…..and without a ton of sequenced backing vocals) then you can make a judgement call on whether they’re any good/talented, according to your own standards, unsigned or not.

Being ‘signed’ used to be perceived as an indication that you were worthy i.e. talented. Nowadays a lot of people know that just isn’t true. Sadly though, I don’t think a lot of people care either.